Denmark’s Cold War struggle for scientific control of Greenland

A three year basic research project has revealed the extent of the top secret political struggles and scientific tangles between the US and Denmark during the Cold War.

As tensions grew between the USA and the Soviet Union after the Second World War, a newly liberated Denmark would find itself caught between the Cold War ambitions of two super powers.

Free from the constraints of five years of foreign occupation, Denmark was keen to exert its position on the world stage and exert their scientific sovereignty over Greenland, which had become a strategically important island to the US during the Second World War.

This story of top secret diplomatic wrangles, military operations, scientific research, and botched media cover-ups, is now documented in a new book “Exploring Greenland: Cold War Science and Technology on Ice.”

“There’s no shortage of intrigue in this story,” says Associate Professor Kristine Harper, a former meteorologist and oceanographer turned historian of science, from Florida State University, USA.

Harper was a senior researcher in the Exploring Greenland Project that ended in 2013 and co-edited the new book published in 2016.

Read More: American adventurer captured 1930's Greenland on film

Declassified documents reveal full extent of political struggles

The book reveals the full extent to which the US government and military tried to gain territorial control of Greenland, and the increasingly three-way ‘David and Goliath’ style politics that ensued between Denmark, Greenland, and the US.

“We already knew that the US was deeply interested in Greenland in the Cold War. But we didn’t know the full extent of their research programs,” says Ron Doel, an associate professor of history at Florida State University, USA, and one of the senior researchers on the Exploring Greenland project.

Revisiting newly declassified archives revealed previously unknown details on the extent of US interest in Greenland and that Denmark had more influence on US activities than is often assumed, says Doel.

The researchers trawled national and private archives on both sides of the Atlantic to reveal new insights on both Danish and US perspectives from the time (see Fact Box).

Read More: Greenlandic fjords get their organic matter from Russia

US interest in Greenland began in the Second World War

The US government first became interested in Greenland during the Second World War, when Denmark was occupied by German forces. With its strategic position, located right in between the US and the war in Europe, the allies were certain that Greenland should not fall into enemy hands.

Greenland was a vital stopover spot for allied aircraft, and weather stations around the country provided essential data for developing accurate European weather forecasts, which were crucial for allied success in battle.

“[The allies] needed to occupy Greenland with their own military forces, as they certainly didn’t want the Germans to occupy it,” says Harper.

Read More: Greenland melt linked to weird weather in Europe and USA

1941: US military moves in

On the same day that German troops marched into Denmark on the 9th April 1940, the US agreed to provide military protection and supply goods to Greenland.

When the US entered the war in 1941, Henry Kaufmann, the exiled Danish Ambassador to the US in Washington, agreed to allow them to build military bases in exchange for recognition of Danish sovereignty.

They immediately got to work, building military bases, airstrips, and research stations. They trained around 7,000 new meteorologists and deployed some of them to weather stations around the Arctic.

In 1944 there were 5,795 US military and civilian personal deployed at bases across Greenland--almost a quarter of the island’s total population (21,412).

By the end of the war, the US Army Weather Service had installed 14 weather stations, as well as operating 13 Danish stations, built before the war. They had even claimed control of several clandestine German weather stations on Greenland’s inaccessible east coast.

See the timeline of US military and scientific interest in Greenland in the video at the end of this article.

War ends and a nuclear arms race begins

After the war, Greenland lost none of its strategic importance to the US. Located almost equidistant between themselves and the emerging threat from the Soviet Union, many in government saw Greenland and the Arctic as the stage for World War III, and a warming, ice-free Arctic Ocean as a new gateway for a US invasion by the Soviets.

“Greenland was absolutely central to the North American continental defence,” says Doel.

“In one article I saw from Time magazine, January 1947, someone at the Pentagon had declared Greenland as the world’s largest stationary aircraft carrier. That captures it. It was their base of operations,” says Doel.

But it was no longer enough to be allowed to operate in Greenland. With the Cold War already in sight, the US government now wanted to own it.

Read More: Climate Change research was born in the Cold War

Denmark is caught off guard

“When the Danish Foreign minister visited the US in December 1946 the US Secretary of State asked him right away to sell Greenland,” says lead scientist Matthias Heymann, associate professor at the Centre for Science Studies in the Department of Mathematics, Aarhus University, Denmark, and co-editor of the new book.

“The Danish Foreign Minister wasn’t aware that this would happen, he went there to tell his American colleagues that the US forces should leave the island,” he says.

“The Danish government were rather shocked by the US interest,” says Heymann. “They weren’t aware, at that point at least, of the immense interest of the US forces in Greenland.”

They offered Denmark 100 million USD, a tempting offer in the economic aftermath of war. But the offer was firmly rejected.

“Denmark is a small country, and they’d just had an experience of being occupied by a strong foreign power in the Second World War. They didn’t want to let that happen again,” says Heymann.

At the same time, tensions were still running high with the Soviet Union, who had only left the Danish island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea that spring.

In rejecting the US offer, the Danish government had drawn a line in the sand: Greenland was not for sale.

Read More: Greenland in numbers: eight key statistics to understand the world’s largest island

Denmark establishes its own research agenda

Denmark would now exert its sovereignty over Greenland in the only way they could.

They immediately set to work clawing back control of key scientific institutions and research activities in Greenland.

Almost immediately they established the Greenland Geological Survey, and funded explorations to map landforms and mineral deposits. And soon, weather stations became a bone of contention.

“Arctic weather stations set up in the Cold War matter a lot in terms of sovereignty,” says Doel.

“If you’re setting up a station in northern Canada with US observers, is this saying that the US has sovereignty over this part of Canada, because Americans are running the weather stations? That sort of plan concerned the Canadians, and it’s also why the Danes wanted to control stations in Greenland,” he says.

Read More: Greenland lags Alaska and Canada in involving locals in climate science

Reality bites and US retains control

The Danish Foreign ministry was keen to take control of the weather stations, but there was just one problem: “They couldn’t do it,” says Heymann. “They repeatedly promised to send staff, even signed contracts defining the amount of staff to be send, but for years to come they didn’t live up to these promises.”

“Scientific institutions in Denmark, like the The Danish Meteorological Institute, were more realistic. They said, ‘We can’t do this, we don’t have the staff, there’s just no way.’ But the foreign ministry responded, ‘We have to comply to protect our sovereignty effectively, so you have to make it work.’ And this went on for years between 1940 and 1950,” says Heymann.

Unable to provide enough trained meteorologists, the US continued to operate most of the stations.

“It’s a small story, but interesting as it shows the enormous interest by the Danish foreign ministry to get full control,” says Heymann.

Resignation in the face of US resources would be a recurring theme in the coming years.

Read More: See what life is like when you study climate change in Greenland

Sovereignty settled in 1951 but conflicts remain

A formal agreement in 1951 set new ground rules for US research in Greenland. It guaranteed Denmark’s full sovereignty over the island, and allowed the US military to maintain their military bases in strictly defined areas. But all scientific and military activities outside these areas had to be approved by Denmark.

“At that point, the Danish authorities felt much more relaxed as the sovereignty concern was settled once and all. But during the 1950s, concerns kept rising again. The Danish government were continually surprised by the enormous extent of US activities,” says Heymann.

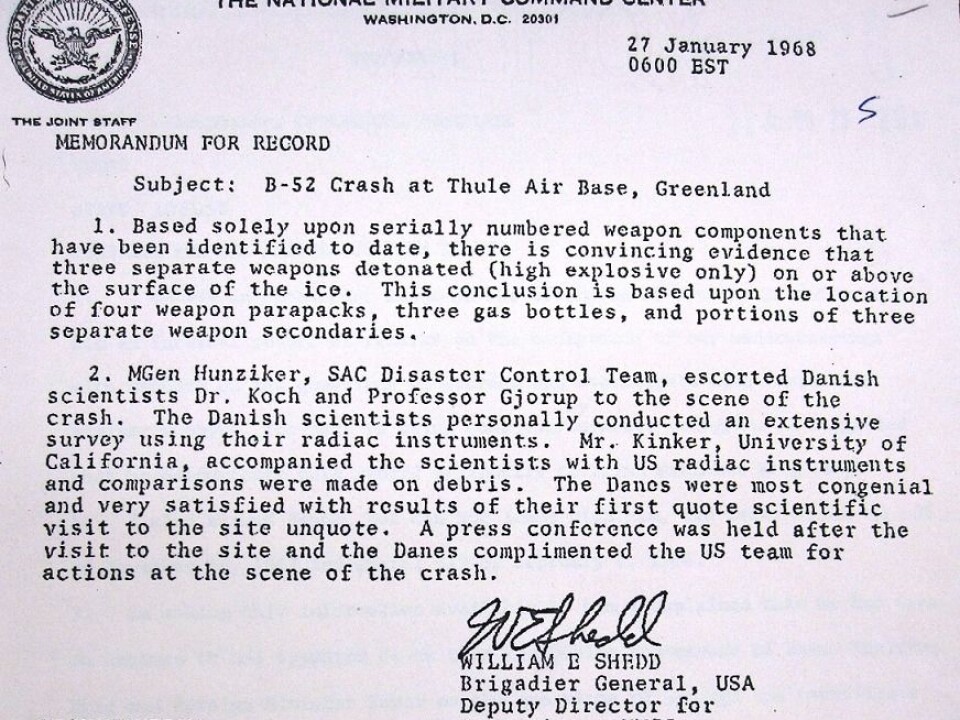

“The major place in Greenland became Thule Air Base in Northwest Greenland. Thule was the largest airbase outside the US territory, which shows how important it was. It was also the hub for all kinds of scientific activities,” says Heymann.

Construction of Thule begun in 1951. In 1954, the US established the TUTO scientific research camp, amongst others, where they launched their explorations and scientific monitoring campaigns on the ice sheet.

Later came Camp Century, a “city under the ice” powered by a nuclear reactor. Controversially, construction began in 1959 outside the designated military areas and without prior approval from Denmark.

Read More: Climate change research was born in the Cold War

Sovereignty challenged at a cocktail party in Copenhagen

The first request related to the construction of Camp Century was an informal letter from the US in 1959. Denmark, fearful of a Soviet reaction, said no.

“Then in August 1959, the US ambassador in Copenhagen informed the Danish Minister of Foreign Affairs informally during a cocktail party, that US forces had already started to build Camp Century on the ice sheet,” says Heymann.

The shocked minister immediately called emergency meetings with his colleagues to discuss their response, but in effect there was little that they could do.

“They felt uncomfortable admitting in any way that the US exercised de facto military sovereignty, which was effectively ceded to the US as Denmark didn’t have the power to stop US forces,” says Heymann.

Read More: International conference brings climate change to Greenland

Danish media censorship failed

Ultimately the project was allowed to continue, and in return, the Danish Foreign Minister insisted on a total media blackout.

But it was too late. Just days before, and unbeknown to the Danish authorities, a US publication, “The Sunday Star”, had published a full feature on the camp. The story was out.

All the Danish Government could do now, was to convince the Parliament and the Danish public that the project was entirely civilian and control press access to the site.

The Danish Embassy in Washington was already censoring journalists’ reports on US activity in Greenland, removing references to anything that was politically sensitive and rewriting the narrative to one of civilian science.

Journalists were permitted to visit, but their trips were severely limited and Denmark forbade all contact between US personnel and the local Inuit.

Read More: The majority of researchers in Greenland are foreign. Does it matter?

US military: a headache for Denmark

The official story told to both the Danish and the US public was that Camp Century was a civilian base, built to “permit year-round studies of weather and snow in a highly strategic area,” according to documents collected during the project.

But Camp Century was much more than that. Here, the US studied all major sub-disciplines in geophysics--seismology, meteorology, climatology, glaciology, geomagnetism, and the properties of ice and snow, says Heymann.

But the real purpose was a test site for innovative polar construction, intended to make way for an even bigger scheme: Project Iceworm, a 135,000 square kilometre military installation designed to hold 600 Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles that could be launched from over 2,000 mobile launchers, hidden beneath the ice on a moving rail-road.

Planning for Project Iceworm began unbeknown to the Danish government. Only the Danish Prime Minister at the time was aware of possible US nuclear activities in Greenland.

The Danish parliament would not find out about plans for Project Iceworm until the 1990s, and many of details are still classified, held in the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Kansas, USA.

Read More: Uncovered First World War documents reveal widespread state censorship

Still a sensitive issue

By the late 1960s, the US military interest in Greenland had begun to subside. New technology made Greenland strategically less important, as medium and long-range ballistic missiles could now be launched from submarines.

Camp Century was closed in 1967, as engineers realised that the ice was not as stationary as they had once thought. And operations at Thule Air Base, once the largest aircraft base in any US territory, were downsized. By 1968 only 1,189 US personnel remained.

Even the question of who should maintain and operate weather stations became less sensitive as they were increasingly automatised.

But the US never left. A fact that remains a politically sensitive issue to this day.

“It’s still a flyover point and it’s still a place where the US military are listening and watching. There are big installations up there and no one will give that up any time soon,” says Harper.

A recent study highlighted another politically sensitive issue brought about by climate change. Scientists predict that waste from Camp Century could once again be exposed as the Greenland ice sheet melts. Leaving a difficult question as to who is responsible for the clean up—Denmark, USA, or Greenland.

Read More: Greenland lags Alaska and Canada in involving locals in climate science

Greenlanders were side-lined

Today, the technology developed by military research activities in Greenland laid the ground work for climate scientists from around the world to obtain long ice cores, both in Greenland and Antarctica.

It was Danish, US, and Swiss scientists that established the first ice-core drilling project for purely scientific reasons. Today, scientists from all over the world fly to Greenland to study the changing ice and oceans every year.

These data have allowed scientists to develop working models of ocean and atmospheric circulation, to reveal centuries of climate change, and confirm the existence of man impact on our climate and sensitive Arctic ecosystems.

But the battle for scientific sovereignty is not over yet.

“It’s a strange story, because it’s all about Greenland, but it’s in the hands of the US and Denmark. The Greenlandic population had no say in what was happening there.” says Heymann.

The Greenland Home Rule was established in 1979 and today Greenland is an autonomous administrative division within the Danish Realm with its own ever expanding scientific research agenda.

Organisations like the University of Greenland and The Greenland Survey ASIAQ in collaboration with both Danish and international research institutions continue to shape the future of scientific activities in Greenland.

See how events in the Arctic unfolded as the US became increasingly interested in Greenland as a place for military activities and scientific research. (Video: Kristian Højgaard Nielsen / ScienceNordic.com)