Greenland lags Alaska and Canada in involving locals in climate science

GREENLAND: There is still a long way to go before the indigenous people of Greenland benefit from environmental research in this vast island nation.

Indigenous Greenlanders who live off their environment are keenly aware of changes happening to the ice sheet, sea ice, and the animals and fish that they hunt.

But their knowledge is a resource that many of the scientists who visit Greenland every year to study climate and environmental change are yet to tap in to, says social scientist Lene Kielsen Holm, from the Greenland Natural Resources Institute.

Not only that, but Greenland’s indigenous people rarely benefit from the research or see the scientific results once they are published, says Holm.

“This is an important part of future research in Greenland and we have to ask for more from the [scientific community],” says Holm. She has been travelling around Greenland for more than ten years, living with and documenting the experiences of Inuit hunters and fishermen in remote communities around Greenland.

“Here in Greenland of course we’re in the middle of the Arctic, and all the world’s eyes are on us with respect to climate change. But the focus is on [scientists] coming from outside and the interaction with local people is very low,” she says.

Mutual benefits of collaborating with locals

Close collaboration between scientists and local communities has benefits for both parties, says Holm. For example, scientists could formulate their research questions with the help of local people.

“Hunters and fishermen are out there every day and have a holistic view of their environment that can put some interesting research questions on the table,” says Holm.

Scientists could also train and employ locals in remote communities to collect data in between their visits. And internationally funded research projects in the Arctic should budget for this, she says.

A determined effort to communicate the results of scientific studies to Inuit populations throughout Greenland is also needed. This means that scientific findings need to be translated into Greenlandic.

But today, only a small number of scientific research programs conducted in Greenland address these issues.

Greenland is lagging the progress made in other Arctic nations

Elsewhere in the Arctic these practices are much more commonplace.

“In Canada they were visionary enough to say that Inuit people should be both involved in the research and benefit from the science. Canadians make data available and fulfil various commitments before the research begins as a way of involving the communities,” says Holm.

“But here in Greenland we don't do that,” she says. “Anyone can come and collect samples from the ice cap and the ocean and then just go back to their respective institutions and make their living there.”

More indigenous scientists is not the answer

Part of the problem is that too few indigenous people train as scientists and can therefore bridge the gap between them and the visiting scientists. But simply training more will not solve the problem, says Holm.

“We are very few people scattered throughout the world’s biggest island. So the question is, how much education is needed? Very often it’s not the most important thing. Proper communication [with the global science community] is actually better,” says Holm.

There is no doubt that visiting scientists have a lot to contribute to Greenland’s growing research environment.

“Most of our money comes from international research,” says Henrik Forsberg, projects manager at ASIAQ—the Greenland Survey who monitor everything from climate to hydrology, mapping, and land surveying throughout Greenland.

“We’re keen to have people invest and come here to do science, but we are also keen to position ourselves as an important part of the science happening here and a good partner to work with.”

“Greenlanders should be involved in this, like in other countries where you’re obliged to have locals involved,” he says.

Progress is being made

Some scientists are already on the track that Holm hopes will become the accepted norm in the coming years.

Professor Bo Elberling, director of the Center for Permafrost (CENPERM) at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, is happy with the steps they have taken to involve locals in many of their research projects in Greenland.

“We’re happy to involve local school teachers, who collect samples for some of our projects. They’re curious about the science taking place in their neighbourhood,” says Elberling, and adds “Teachers are an important link to the next generation, so this is very important to us.”

Elberling and colleagues also disseminate their findings during summer tours to their field sites, with signs in English, Danish, and Greenlandic to explain their research projects in the area. He is also keen to discuss findings with locals to compare their experiences.

“In fact, we have learned a lot from locals,” he says.

He has seen first hand how Greenlanders are more concerned by the unpredictability of the weather and sea ice, rather than the long term predicated changes in temperature or snow.

“We can provide data on actual conditions or model simulations for mean values in the next 10 to 100 years, but it’s far more difficult to provide a weather forecast relevant for the locals to make decisions for the near future,” says Elberling.

Holm herself is currently involved with a large European Union funded project--ICE-ARC--to assess the social and economic impacts of the declining Arctic sea ice.

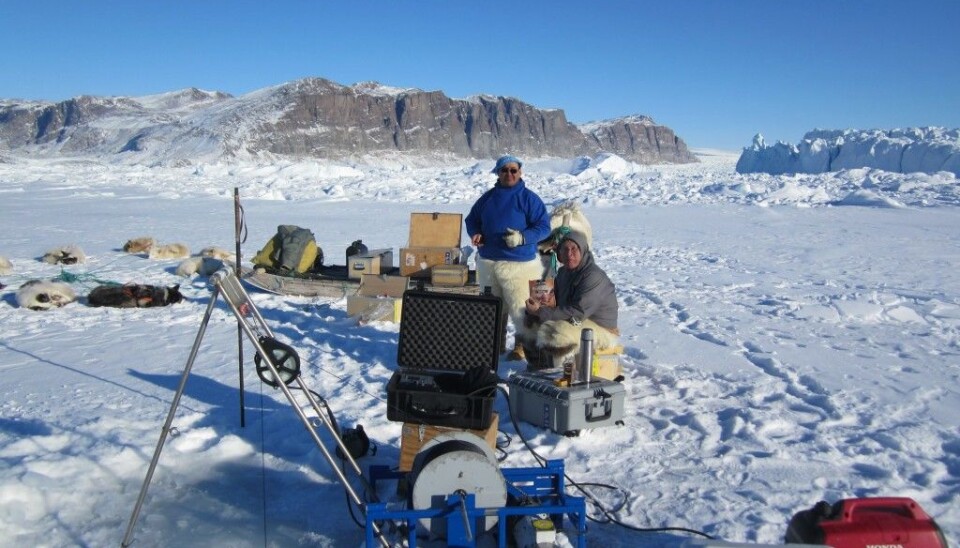

She is helping scientists from the British Antarctic Survey and the Danish Meteorological Institute to foster collaborations with local Inuit hunters in northwest Greenland. They are building and testing equipment to attach to hunters’ sleds to measure sea-ice thickness.

“This is how it starts. Hopefully more and more people will learn from these experiences, and in a few years time we can come up with some best practice solutions to involve Greenlanders in Greenlandic research,” says Holm.