See what life is like when you study climate change in Greenland

Scientists study uncharted waters and living fossils to document sea ice melt in Northeast Greenland.

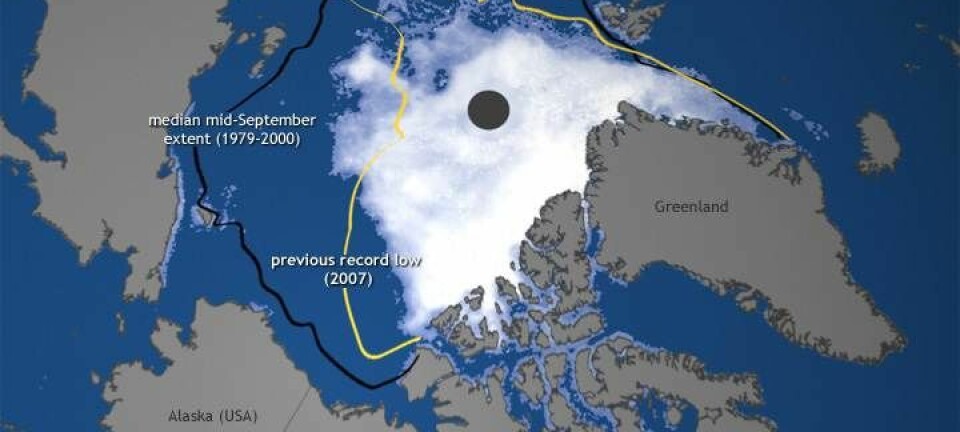

Every year for the last nine years, climate scientists have reported every increasing ice melt in the Arctic.

Marine geologist and biologist Sofia Ribeiro from The National Geological Surveys of Denmark and Greenland, is one of the scientists collecting these vital measurements and comparing them against their predictions.

"When the sea ice melts, here where I research [Northeast Greenland], it introduces lots of freshwater into the ocean, which affects the Gulf Stream. This is important for Northern Europe, as it makes the winters colder," she says.

Battling polar bears to research climate change

Ribeiro works at a relatively understudied region in Northeast Greenland where she and her colleagues carry rifles and radios to protect themselves against the risk of polar bear attacks.

But despite dangers, the area is perfectly suited for researching melting sea ice, she says.

"In the fjords in north eastern Greenland we can collect highly detailed sediment samples. We can follow different biomarkers and changes in the sediment such as grain size, and microscopic fossils. The combination of these three gives us very specific detail about the climate," says Ribeiro.

Her research focuses on climate change during the last thousand years and the sediments that record climate changes throughout this time: from the relatively mild climate of the medieval warm period around 1,000 years ago, to the so-called Little Ice Age that lasted until around 1900, and the global warming that we are experiencing today.

Living organisms in sediments record climate changes

A few years ago, Ribeiro and her research team discovered something remarkable when looking at fossils of phytoplankton in the sediments: some of the phytoplankton was still alive—and had been so for around 100 years.

“Species of phytoplankton are very plastic and susceptible to change, and they are very diverse. Their stock and genetics will change depending on the environment, and so we can study the climate through their development," says Ribeiro.

But this also works the other way. By studying these tiny microalgae, scientists can investigate how future climate change will affect phytoplankton and marine life.

See how Ribeiro examines these seabed sediments in the video at the top of the article.

—————————

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Scientific links

- Phytoplankton growth after a century of dormancy illuminates past resilience to catastrophic darkness, Nature Communications, 2011, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1314

- Hundred Years of Environmental Change and Phytoplankton Ecophysiological Variability Archived in Coastal Sediments, Plos One, 2013, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061184