Uncovered First World War documents reveal widespread state censorship

BASIC RESEARCH: The Danish government practised heavy surveillance and censorship of telecommunications during the Great War.

This article is part of our Basic Research theme

The Danish government introduced extensive surveillance and censorship on all telecommunications passing through the kingdom during the First World War.

Inside a document entitled “The Black List,” the Danish Foreign Ministry kept a long list of names on people who were to be kept under watch.

Some were well-known public figures like politicians and intellectuals, but many ‘ordinary’ people were placed on the list as well

Denmark wanted to stay out of the war, so the Danish authorities wanted to contain any potentially dangerous information that could offend the warring nations or otherwise harm the kingdom's interests.

“Monitoring and censorship efforts were continuously stepped up during the war,” says Andreas Marklund who is a researcher at ENIGMA – Museum of Communication in Copenhagen, Denmark.

“Telegrams are interrupted, stopped, and disappeared. Correspondence of named people was closely observed. Simply put, Denmark introduced comprehensive censorship,” he says.

Marklund recently went through the old surveillance records kept in the Museum’s archives, which is now described in a paper in the journal: History and Technology.

Journalists and politicians on The Black List

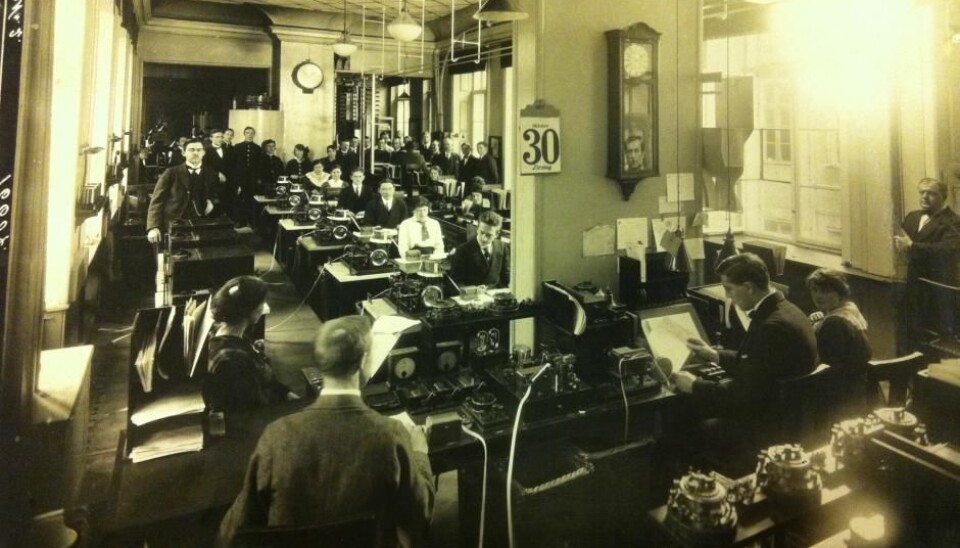

During the war, the Danish Foreign Ministry created a censorship corps located in the main telegraph station. At first, they monitored telegrams, but later they also began monitoring telephone conversations.

“Both journalists, politicians, ordinary citizens, and foreigners were regarded as suspicious people who could spread information that could harm Denmark,” says Marklund.

At the beginning of the war their activities were restricted to editing telegrams, but later strict instructions were introduced that dictated what content could or could not be communicated via telegram.

In 1917, censors decreed that telephone conversations could only be conducted in a Scandinavian language. This allowed telephonists to listen in and interrupt any conversations they considered dangerous.

“As of the 25th of this month, telephone conversations on state telephone lines can only be conducted in Danish, Norwegian, or Swedish. Any telephone conversation conducted entirely or partly in another language will immediately be disconnected,” read the full message from telegraph director N.M. Meyer to all stations in May 1917.

Historian: “It’s due diligence”

Today, this level of censorship may sound like a breach of basic civil liberties and freedom of expression, but Nils Arne Sørensen, a history professor from the University of Southern Denamrk, disagrees.

Most people at the time would have considered it “due diligence” he says. They would have understood the risky situation Denmark could have found itself in, if it had become known as a centre of espionage. Most people would have taken great care with their communications, he says.

He is not at all surprised that the government introduced such strict censorship--the type that would be considered illegal by today’s standards and even unconstitutional in many parts of the world.

“It’s of course a grey zone and historically interesting. Denmark is a pragmatic country and there were some good and conservative officials who prioritised national security. The country was in a very serious situation,” says Sørensen.

“Freedom of speech was never absolute”

Sørensen draws a parallel to the situation today.

“We’ve seen terror plots that have been uncovered. I might be a naive and trusting person but I believe that state surveillance [in Denmark] today, happens under judicial approval. I don’t know for certain, but I think we’re all glad that the police stop people before they complete an attack,” he says.

He emphasises that freedom of speech has, historically, always been tempered according to circumstance.

“Freedom of speech was never absolute,” he says. “It should always be framed by common sense, and [during the First World War] it seems to have been done exactly as such. Of course other things surely took place, which weren’t so sensible, but there were significant interests at play,” he says.

Marklund agrees.

“Communication has never been totally free, and the state continued to monitor and censor after the war was over. The state has always been afraid of cross-border communication and it’s the same today,” says Marklund.

-------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex