Everything you ever wanted to know about the history of haemorrhoids

Warning: Includes spanking and leeches around the anus.

Haemorrhoids are one of the best-described diseases in medical history.

There are a huge number of suggestions as to why you get them and how you can get rid of them, but even today, there is no consensus about the best treatment.

Throughout our history, diseases have haunted humanity. Many were most likely the same as we see today, but most of them were poorly understood, and their names are often hard to interpret.

Ulcer of the stomach, appendicitis, colorectal cancer, and cirrhosis of the liver, were first described fairly correctly in the 18th century, and myocardial infarction (heart attack) even later.

So, it is pretty difficult to be sure of which diseases our ancestors suffered and died. Examination of skeletons as well as chemical and molecular biological investigations sometimes give valuable information.

However, one group of diseases is different: haemorrhoids and other disorders of the anus have been described fairly precisely from as far back as ancient times and from all parts of the world.

The reason is undoubtedly that these diseases were common, directly observable, and present with rather simple symptoms such as pain and bleeding. But even so, the understanding of their origin and treatment has varied a lot over the years, and this continues up to present day.

Here, I describe a number of different assertions and recommendations that have appeared throughout the past 2,000 years and beyond. But, I do not attempt to offer a definitive answer as to the best treatment. Unfortunately, haemorrhoids are still a bit of a mystery.

Read More: Medicine in Antiquity: From ancient temples to Roman logistics

What are haemorrhoids?

Haemorrhoids are clusters of vascular tissue, smooth muscle, and connective tissue, arranged in three columns along the anal canal—the final four centimetres of the digestive tract, stretching from the rectum to the anus. These clusters are named the anal cushions.

Haemorrhoids are quite normal structures, and are present in all individuals, but we only use the term for pathologic or symptomatic haemorrhoids. According to their location they can be divided into internal haemorrhoids, located in the upper part of the anal canal (above a mucosal fold called the dentate line), and external, located below.

Internal haemorrhoids are characterised by bleeding and varying degrees of prolapse, and may be followed by itching, pain, mucus discharge, and faecal seepage. External haemorrhoids usually only give major symptoms when they thrombose and are then very painful.

However, many patients with these symptoms do not actually have haemorrhoids, and a thorough examination of the area is always recommended in order to exclude other, possibly far more serious diseases.

An encyclopaedia with 227 pages about haemorrhoids

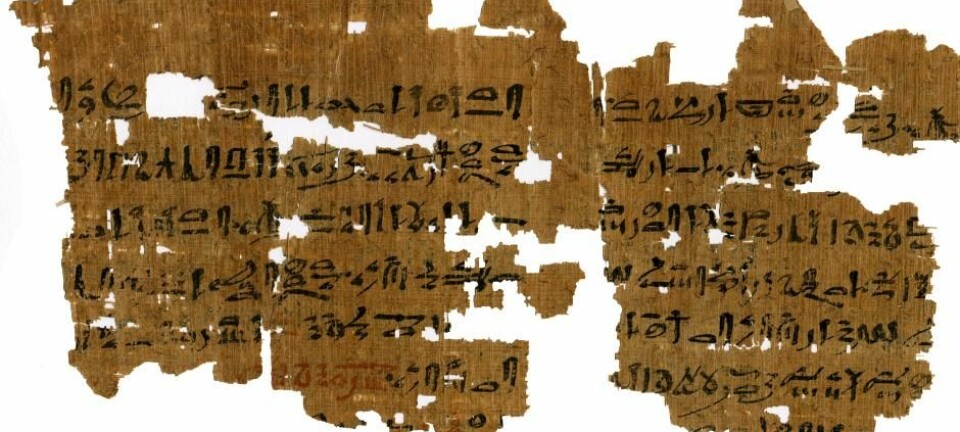

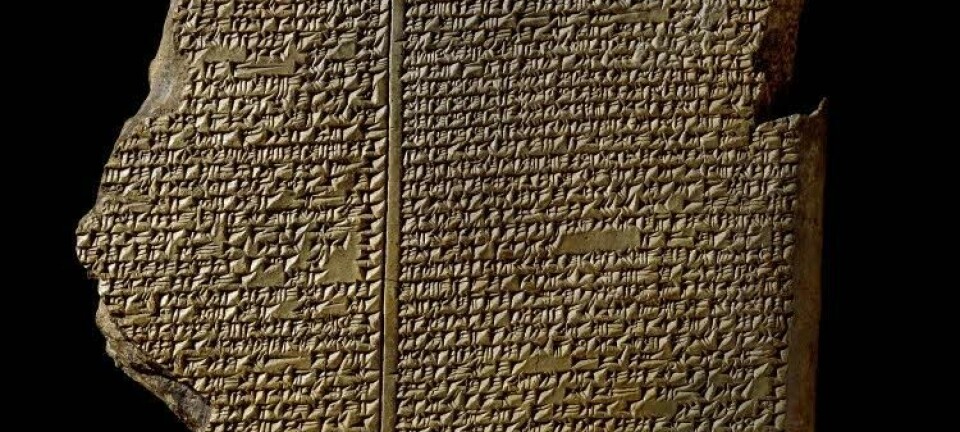

The oldest convincing descriptions of haemorrhoids and other diseases of the anus and anal canal date back to 1500 BCE in Mesopotamia. But there are even older records in Indian and Chinese literature, although we do not know exactly how old these are. The Egyptian “Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus” from about 1200 BCE deals exclusively with these diseases, and the old Europeans as the Greek Hippokrates (c. 460 to 370 ) and Galen (129 to c. 216), who worked in Rome, wrote numerous extensive papers on the same subject.

Since then, many famous doctors have written pages upon pages on the topic of haemorrhoids.

For instance, Francois de Montègre wrote 227 pages on haemorrhoids in the great French Encyclopaedia published in 1817. He classified 20 variants. As a side note, a Danish Encyclopaedia from 2001 dedicated just half a page to the subject.

The famous German pathologist Rudolph Virchow used 30 pages in his large book on tumours from 1863, and the American William Bodenhamer in 1884 wrote a book of nearly 300 pages entirely about haemorrhoids.

More recently, there is at least one new article every week published in medical periodicals on the topic.

Read More: Clay tablets from the cradle of civilisation provide new insight to the history of medicine

Appeasing the gods of haemorrhoids and amulets of dried toads

In antiquity, and even later, diseases were regarded as being the result of bad habits and under the influence of the gods, demons, stars, seasons, and the weather.

The recommended treatment, besides following a sensible way of life, was to appease the god or to cast out the demon. It was also wise to protect oneself with amulets, and here various stones could be used as well as dried toads. Remarkably, you can still find people recommending amulets on the Internet today.

By about 400 BCE the theory of humoralism emerged. This said that disease was caused by an imbalance of bodily fluids (blood, phlegm, and yellow and black bile). Accordingly, the treatment consisted of re-establishing a balance by inducing vomiting, coughing, sweating, urination or defecation, or by blood-letting.

Haemorrhoids are explained as a stagnation of blood, phlegm, and black bile in the blood vessels in the anus, and bleeding from haemorrhoids was regarded as a good sign, which should not be stopped completely. The vessels in the anus were therefore called “golden veins.”

Develop haemorrhoids for a long life

The theory of humoralism dominated European medicine for more than 2,000 years. And the German physician Michael Alberti (1682-1757) even wrote, “Hæmorrhoides esse Longævitatis causam” Meaning “haemorrhoids are the cause of a long life.”

An attempt at an anatomical explanation came at the same time from the Italian anatomist Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771). He thought that they were caused by our upright posture, the length of the blood vessels (veins) to the anus, the lack of venous valves, and an elevated pressure in the vessels as in cirrhosis of the liver.

This explanation fits poorly with the fact that varicose veins occur most frequently in the legs, where there are long veins with plenty of valves, and haemorrhoids are not more common among patients with cirrhosis than any others.

Genetic factors have also been proposed, and many authors have maintained that haemorrhoids were particularly common among certain groups, such as Jewish people. This is perhaps related more to widespread antisemitism than anything else. And to be clear, it is not supported by any scientific evidence.

Read More: Unpublished Egyptian texts reveal new insights into ancient medicine

Riding trains, spanking, and other strange suggestions

As recently as the 19th century you could come across the idea that bleeding from haemorrhoids is the male equivalent to female menstruation, and just as beneficial.

Other suggested causes include, gender, age, climate, geography, diet, overweight, pregnancy, diseases of the pelvis minor, idleness, masturbation, anal intercourse, regularly riding the trains (referring to railway workers), riding horseback, wearing too tight clothes, spanking, and cleaning the area with hard printed paper like a newspaper.

Some authors have described haemorrhoids as erectile tissue like in the penis, a kind of hernia, and a consequence of phlebitis—inflammation of the veins.

None of these suggestions has been convincingly confirmed.

More recently, a low fibre diet and constipation have been suggested as potential causes, but neither has been proven, and haemorrhoids are more often associated with diarrhoea. Straining at defecation does not seem to be of significance.

According to more recent theories, haemorrhoids are a consequence of changes in the connective tissue, and recent investigations indicate a possible association with diseases of the peripheral arteries such as coronary occlusion-- the partial or complete obstruction of blood flow in a coronary artery.

Medical treatment was for the rich

If it did not help to implore the gods, one had to look for more tangible methods.

You can read all about the recommendations of famous physicians, but professional treatment was for the rich few. Everyone else was left to seek help from quacks or rely on folk medicine, up until the middle of the 19th century.

Their treatments were often quite imaginative.

But it is not always easy to distinguish between professional treatments and alternative methods.

Read More: Conflict between alternative medicine and medical sciences stretches back to the 19th century

A flood of unsuccessful methods

Many have recommended eating more digestible food. Supplemental dietary fibre seems to be able to reduce symptoms but does not cure the disease.

Some recommend squatting during defecation. However, this is slightly undermined by the fact that people who chew khat often sit for hours in this position and have far more haemorrhoids than others. They also suffer from constipation.

Doctors generally agree that exercise is a good remedy for constipation, so this has probably helped some patients. While a large study of treatments using herbs from traditional Chinese medicine was shown to have no effect on bleeding.

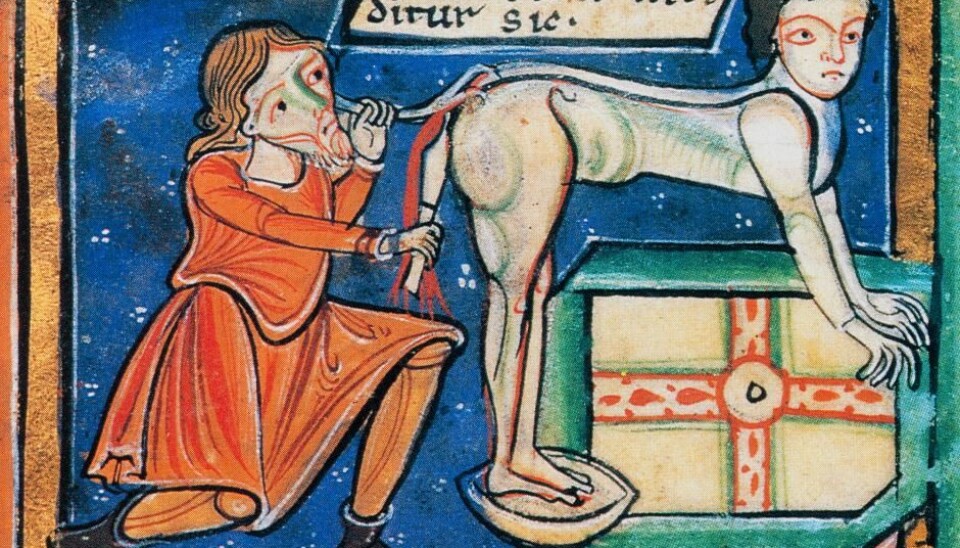

Up until the middle of the 19th century, many physicians recommended blood-letting (preferably from a certain vein near the ankle), leeches around the anus (up to 20 in a week), and even cupping on the loins.

Other recommendations included laxatives, herbal medicine, hot and cold sitz baths, electric current, radium capsules, acupuncture and moxibustion, and local anaesthetics. Some of these methods may have reduced symptoms, but none has been able to cure haemorrhoids, and a some of them can be harmful.

In recent years, scientists have tested a group of substances called phlebotonics as a treatment. They have an effect on blood vessels and lymphatics and may thereby reduce bleeding.

The most effective solution for more advanced disease is today to remove the haemorrhoid. A popular procedure is to place a small rubber band at the base of an internal haemorrhoid. This leads to necrosis and sloughing of the tissue. And there are many other methods.

We still know far too little about haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids are among the most common diseases in the world. We have known about them for thousands of years, and the literature comprises a vast number of publications about their causes and treatment.

Modern medicine offers about twenty different medical and surgical methods of treatment. Even more can be found among alternative therapists, including amulets, magnetic therapy, healing, and acupressure.

We know what haemorrhoids look like under the microscope and we know a fair bit about what they are made of.

Unfortunately, we still do not know how common they are, what produces them, and what is the best treatment.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

Translated by: The author