Medicine in Antiquity: From ancient temples to Roman logistics

A showdown with religious dogmas, an early scientific approach, and diligent use of plants were some of the ingredients of ancient medicine. Welcome aboard a historic journey to Greek temples, body fluids, and Roman hygiene.

We usually regard the Greek doctor Hippocrates as the father of the Western medicine. His greatest achievement was to separate healing from religion and apply natural science methods – an early medical science that was in use centuries before the Christian era.

In contrast, the Romans looked down on physicians, but they were good with logistics and hygiene. Their drinking water supply was legendary: Miles of watercourses brought fresh water from the mountains to the cities, which were kept separate from the waste water.

It is not unthinkable that this was more important for survival than medical treatments.

But how did the Ancients perceive disease? And how were they treated? We dive into this history, on a journey that includes Greek temples, human body fluids, and Roman hygiene.

Illness was a religious matter

In ancient Greece, treating disease was a religious concern that stretched right to the top.

The god of healing was Apollon, the son of Zeus. Apollon handed much of the medical work over to his son, Asclepius, the god of medicine. He in turn delegated the work to his five daughters and three sons, of which Hygieia stood for cleanliness and is the name sake for the field of hygiene.

Doctors were organised in family guilds, and work was passed down from father to son. The patients came to Asclepius temples to be cured using a mixture of medical art and religious spells.

This connection between the medical profession and the temples lasted from about 600 to 300 BCE.

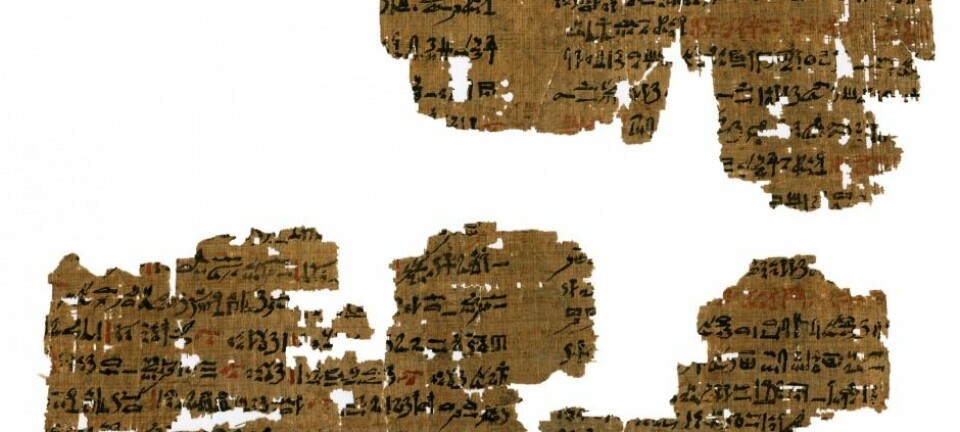

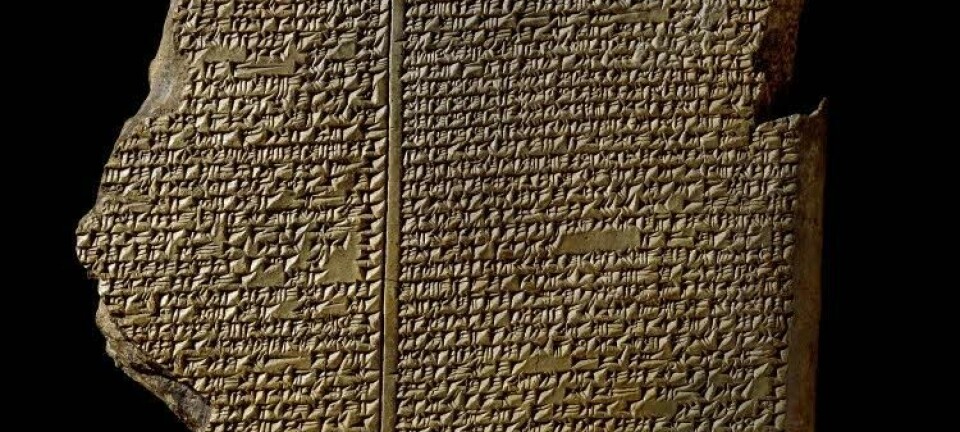

Read More: Clay tablets from the cradle of civilisation provide new insight to the history of medicine

Hippocrates took medicine out of the temples

The biggest contribution that Hippocrates (about 460-375 BCE) made was in moving medicine out of the temples. He concluded that sickness was not the wrath of the gods, but instead, it was due to natural causes.

Even though he lacked evidence to support this – there was a pronounced taboo against dissection of humans in Ancient Greece – he followed a science-based approach to his studies of medical science and disease.

According to Hippocrates, the patient underwent a critical phase, meaning the time when either the disease or the patient could win. However, the disease could still take revenge in the form of a relapse, and then the patient had to wait for a new crisis. Treatment was mostly confined to bed rest in order to strengthen the patient during this struggle.

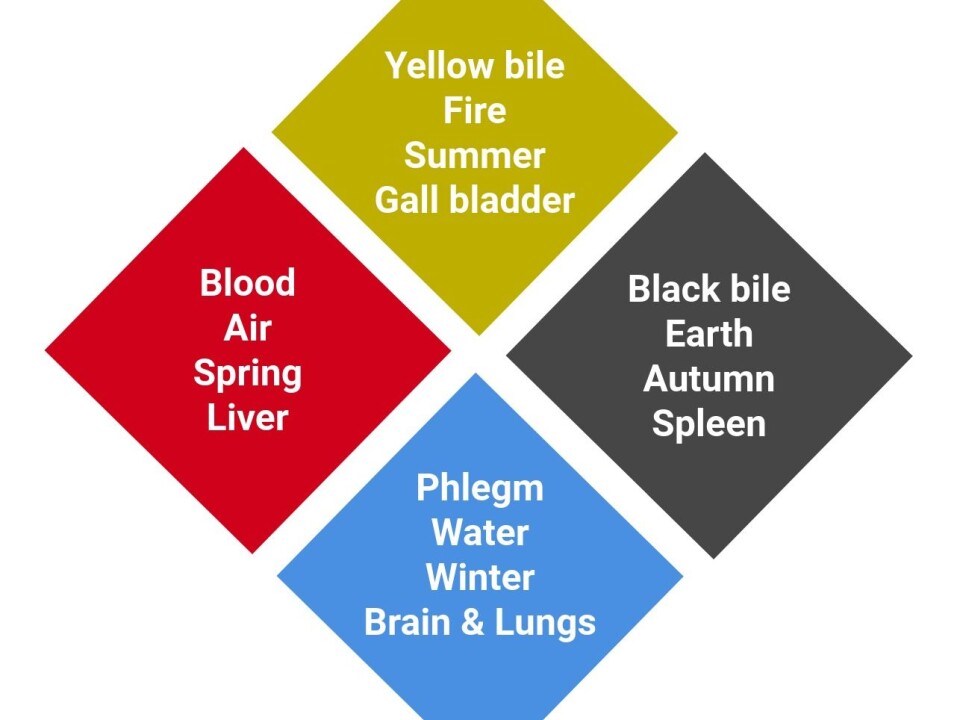

In time, the four humours of Hippocratic medicine (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and mucus) became associated with the four elements (air, fire, earth, and water) corresponding to the two contradictory conditions: Dryness-humidity and heat-cold.

The Greek-Roman doctor Galen (119-199 CE) further developed humoral pathology and combined it with the natural perception of bodily fluids, natural elements, and Aristotle’s (384-322 BCE) view of nature. Illness could, therefore, be attributed to an imbalance between these four humours.

Humours also determined our mood

Personalities could now be characterised by the surplus of the different bodily humours – a remarkable link between psyche and the body. Air was paired with blood (Lat. sanguis), which was thought to be produced in the liver. An overproduction of blood made you sanguine: Happy and optimistic.

Fire was associated with yellow bile (Gr. chole). This was thought (almost correctly) to be produced in the gall bladder, and overproduction gave the person a choleric temper: Upbeat and angry.

The gloomy mindset and depression of melancholic types, was due to an excess of black bile (Gr. melan chole), which allegedly came from the spleen and was linked to the earth.

The brain was ascribed to produce mucus (Gr. phlegma), and a surplus produced a phlegmatic (sluggish) temperament.

The excess of a harmful fluid should be removed by suitable means, via a vomitive, laxative, or diuretic. A surplus of blood was removed by bleeding, which over the years has killed significantly more patients than the few who benefited from this treatment.

Read More: Ancient Roman artifact found on Danish island

Wounds were cleaned with wine

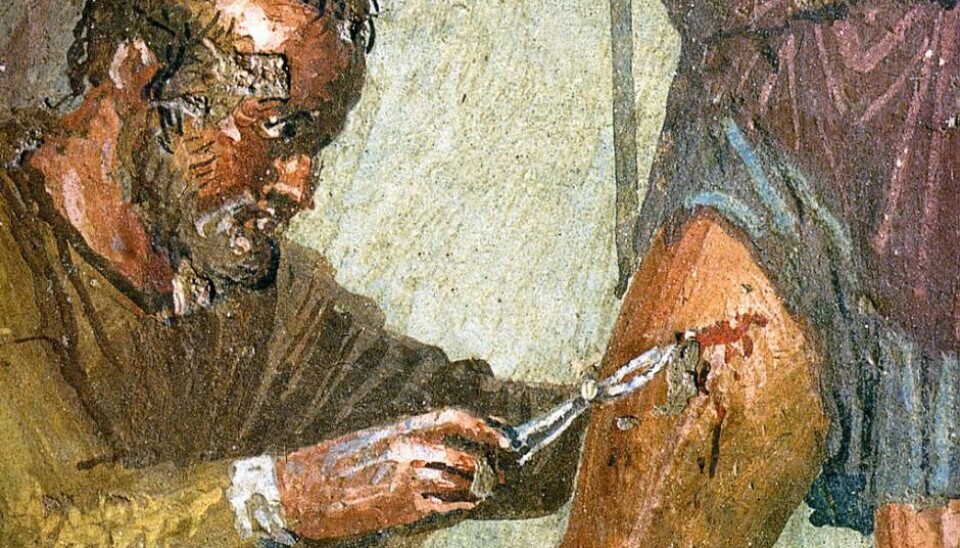

Surgery consisted predominantly of repairing battlefield or sports injuries. Actual interventions were rare and limited to hernia, removal of bladder stones, and burning of haemorrhoids.

Many of the doctrines of surgery were quite reasonable: Wounds should only be cleaned with wine since the water was contaminated; clean cuts should be kept dry so that they can heal; all blood should be emptied from the wound, and wounds with broken tissue should be cleansed of pus and ample drainage provided to avoid infection.

Bleeding was stopped by cold wrapping, compression, or burning.

Hippocrates writes: “What is not healed with medicine, is healed with the knife; what the knife does not heal, is healed with the cautery, and what the cautery does not heal must be considered incurable.”

Orthopaedic surgery involved more reasoned treatments. Patients with fractures were stretched to relieve the fracture site and promote setting, and to prevent a shortening of the fractured bone, which caused the patient to limp.

Sporting activities offered plenty of opportunities to put dislocated joints back into place. Dislocated shoulders were fixed by pushing the heel into the armpit of the lying patient while pulling and turning his arm – a procedure that has not changed over the past 2,300 years.

Herbs and plants were popular drugs

Medications used included mandrake, hemlock, henbane, and other plants belonging to the Solanaceae (nightshade) as narcotics. Mandrake was used to treat seizures, depression, and malaria.

Other treatments included apices such as chamomile, wormwood, cumin, anise, and rosemary.

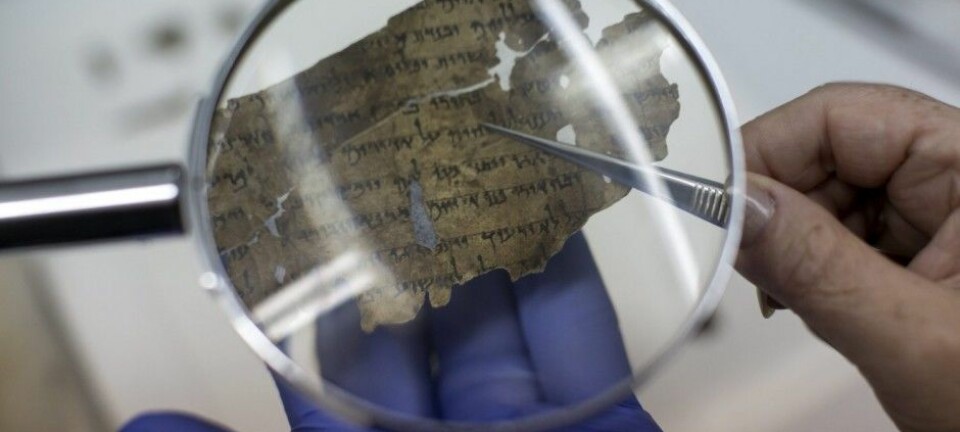

We know this from the first written sources from the first century CE and from seeds excavated from the remains of temples.

Hippocrates’s methods influenced the following 2,300 years of medicine, thanks to Galen of Pergamon, who cemented the concept of humoral pathology.

This ‘spell’ was not broken until Rudolf Virchow in 1858 put forward his ground-breaking work of the biological understanding of the onset of disease.

Read More: Pompeii residents were screwed before the volcanic eruption

The Greeks of Alexandria

Alexander III of Macedonia (Alexander the Great, 356-323 BCE) is reported to have said “I die with the help of too many doctors.” But before that, he founded Alexandria and made the city the centre of science – a position that was established with the construction of the Library in Alexandria at the end of the third century BCE.

It was here that Herophilus of Chalcedon (330-260 BCE) came up with the theory that the brain controlled the rest of the body. He distinguished between the functions of the brain and the cerebellum, and connected the nervous system with movement and sensation.

He also described the flow of blood from the heart into the arteries, and even invented the water clock in order to achieve reproducible pulse measurements.

The Romans looked down on doctors

The Romans had a diametrically opposed relationship with doctors.

Roman education included a detailed knowledge with the philosophers, and as medical science was based on philosophy, self-care was a natural progression.

The Romans’ medical insights were therefore in-line with folk medicine.

Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE) said to his son: “I forbid you any communion with doctors!”

But if the Romans had inferior medical insights, they were supreme in terms of logistics and hygiene.

Aqueducts brought clean water from the mountains into towns via an extensive network, where sewage and drinking water were strictly separated. This preventative effort may have saved more people than the treatments of the Greek doctors.

Read More: Bull fat, bats blood, and lizard poop were the drugs of choice in ancient Egypt

Galen’s theories undisputed until the seventeenth century

Galen studied medicine for four years in Pergamon, followed by studies in Smyrna, Corinth and Alexandria. In 157 CE he became a doctor at the gladiator school in Pergamon and was later appointed physician-in-ordinary for emperor Marcus Aurelius.

He was very self-assertive: “The one who wants to be famous only needs to get into what I've explored throughout my life.”

His ideas, which were based on animal dissections and matched the perceptions of the church, were undisputed until around 1550 CE.

Galen divided diseases into three categories, which were conditional upon:

- Physiological causes that we cannot influence: Innate or outward conditions (gender, age, temperament, climate, and seasons).

- Controllable conditions (food, drink, exercise, and bathing).

- Causes that contradict physiological conditions (pain, mental causes, and all processes that can cause disease).

The treatment was almost Hippocratic, discharged by vomiting, coughing, stools, urination, sweating, or bleeding.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Ole Sonne

Scientific links

- 'Grækerne', Dansk kemi (2016) (In Danish only)

- 'Egypterne', Dansk kemi (2016) (In Danish only)

- 'Romerne', Dansk kemi (2016) (In Danish only)

- 'Antikkens verden', Aarhus Universitetsforlag (2011) (In Danish only)