Conflict between alternative medicine and medical sciences stretches back to the 19th century

Unorthodox healers recommended ‘morally correct’ remedies such as less sex or eliminating certain foods from the diet, while the medical establishment prescribed mercury and narcotics.

Medicine is today a highly specialised science, advanced by costly laboratory research published in esteemed scientific journals, following strict criteria for scientific evidence.

Meanwhile, unorthodox or alternative medicine thrives on divergent theories, which are more or less in conflict with orthodox medicine.

This division stretches back to the 19th century, where the central themes for the modern conflict between orthodox and unorthodox medicine emerged, and it is the topic of my PhD thesis.

Let’s take a tour of some of the key ideas and movements in alternative medicine that have run up against medical orthodoxy since the early 1800’s.

19th century: Better diagnoses but lack of treatments

The 19th century saw a dramatic development in medical science. At the turn of the century, scientists abandoned the theory that good health could be derived from the right balance between fluids in the body, even though this Hippocratic theory had been a cornerstone of medicine since antiquity.

Modern medical sciences searched for specific causes for specific illnesses. This change began in large public hospitals, especially in Paris, where the vast number of patients provided an inexhaustible source of research material, and diagnoses were promptly tested via autopsy.

Later, medical research moved to the laboratory where the microscope allowed scientists to study and isolate the bacteria for anthrax, cholera and tuberculosis.

An increasing number of illnesses could be diagnosed and medicine could explain more of human health, but still by 1900 doctors were incapable of curing several serious and rather common illnesses.

It was not until antibiotics came along in the middle of the 20th century that doctors were able to treat infectious diseases like tuberculosis.

Read More: Clay tablets from the cradle of civilisation provide new insight to the history of medicine

Bleeding gums and narcotics

The so called ‘heroic therapy’ was practiced well into the 19th century by orthodox doctors. The principle behind the heroic therapy was that severe illnesses could only be treated with harsh therapies, which led doctors to use frequent bleedings and strong medication on already weak patients.

Mercury compounds were especially popular and were generally given until the patient’s gums started to bleed and the teeth became loose. This, apparently was to ensure that the drug had started to work.

The growing medical industry in the middle of the 19th century introduced lots of strong painkillers, which we today categorise as narcotics. But even by around 1900, doctors were often only able to diagnose the illness and prescribe a painkiller or a calming drug to show that he had at least done something.

The 19th century also marked a turning point in access to medical care. Until this time, doctors had only worked for wealthy citizens in the large cities. But in the 19th century many western countries began to develop different kinds of healthcare and for the first time everybody in society had access to educated doctors.

Rejection of the orthodox treatments

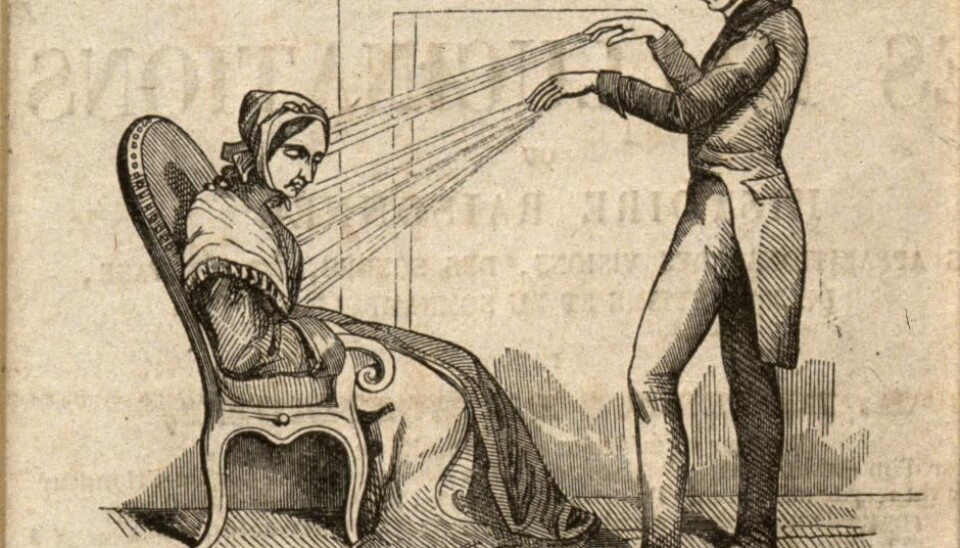

Several popular movements began to arise in opposition to the harsh therapies, strong drugs, and orthodox medical authorities in the 19th century.

Most of them promoted a more natural way of healing through changes in lifestyle or non-toxic treatments. And even though they challenged medical authorities, they also set out to present their own theories as scientifically viable and to establish medical schools and journals.

The American pastor Sylvester Graham was one of the first of many such health reformers. From the 1830’s he promoted his own health program, known as the ‘Science of Human Life.’

Every human illness derived from too much stimulation, so the theory went. In particular, overstimulation of the alimentary system could spread through the nerves and cause illnesses in other parts of the body.

Read More: Medicine in Antiquity: From ancient temples to Roman logistics

Less sex, meat and white bread

For Graham, what was morally wrong was also unhealthy. Meat was harmful, not only because it was morally wrong to kill, but also because it stimulated the body too much.

The same problem arose from the use of alcohol, tobacco, coffee, tea, and spicy food. White flour also contained too much stimulation, only wholemeal flour provided nutrition.

Sex more than once a month was also too stimulating even for young and otherwise healthy individuals, he said. While older and weaker people should definitely partake in sexual activities less frequently, and masturbation was out of the question. Also, polluted air in crowded rooms, especially ballrooms, theatres, and gaming halls, was to be avoided.

Health as religion

Coincidently, staying healthy also became a moral duty. Graham and his followers trusted that the adoption of these principles would eliminate illnesses. And as subsequent generations became healthier and more moral, human life expectancy would increase by several hundred years.

Today, health is sometimes criticised as being used as a religion. But Graham lived in an era less frightened by religion and actually wanted to strengthen religious society explicitly, through physiological arguments.

Read More: The history of anti-rheumatic medicines is one of hope and disaster

Distrust of drugs

Today, there is a great deal of scepticism towards drugs and vaccination among the general public, who prefer a more ‘natural’ or non-chemical way of healing.

This was also one of the primary reasons behind many of the health movements of the 19th century: Grahamism rejected conventional medical therapy with drugs, because it could only relieve the symptoms and never got to the real causes of the illness. Medicine and vaccinations were considered poisons, which stimulated the body too much.

The inventor of homeopathy, Dr Samuel Hahnemann, rejected what he saw as the lavish use of strong drugs. He was convinced that illnesses should be cured with substances that gave the same symptoms in healthy people that the illness produced in sick people. Furthermore he thought that the active substance should be diluted in water or alcohol until almost every molecule of active substance was gone. This, he said, would make the remedy less harmful and more healing.

95 per cent of all illnesses derive from the spine

Another healer D. D. Palmer had the same distrust of drugs and vaccinations, but developed a rather different approach to therapy.

In 1895 he invented chiropractic, which he said could cure 95 per cent of all illnesses by manual adjustment of the spine. The last 5 per cent could be cured with adjustment of other joints in the body.

Palmer believed that all illnesses were caused by the flow of what he called innate intelligence – a kind a cosmic energy given in the moment of birth. This flow was hindered by small displacements of the joints, he said. At the same time, he rejected every other remedy from drugs to diet and from surgery to hydrotherapy.

Read More: What are the major challenges to modern medicine?

Back to nature – civilization makes us sick

Another alternative to chemical drugs was the German method of hydrotherapy. In the USA, hydrotherapy was combined with Graham’s vegetarianism to form the naturopathy health reform movement in the late 19th century.

The basic principle for naturopathy was that life in modern civilization was unhealthy. Every illness came in some way or another from inadequate metabolism and internal poisoning derived from incorrect lifestyles dominated by tobacco, alcohol, meat, lack of exercise, and an imbalance of work and recreation.

Even in the Danish branch of the movement, which was far from radical, it was commonly accepted that a healthy body could not be harmed by bacteria as long as it was protected by a healthy metabolism.

The notion that good health comes from a natural way of life is still popular but neither today nor in the 19th century was there any agreement about what exactly constituted ‘a natural way of life.’

Interestingly, unorthodox movements appear just as access to educated doctors was opened up to all in society, and remains popular despite huge progress in medical science. Perhaps it just all comes down to the individual, who thinks they know what is best for their health.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

Scientific links

- 'Kiropraktikkens historie i Danmark' Per Jørgensen (2014)

- 'Skodsborg Badesanatorium- på kanten af det offentlige sundhedsvæsen og den ortodokse medicin i 1898-1992' (2018) PhD thesis by Anders Bank Lodahl

- 'Crusaders for Fitness: The History of American Health Reformers' James C. Whorton (1982)

- 'Nature cures: the history of alternative medicine in America' James C. Whorton (2002)