Don’t blame the pigs for new flu types

Pigs have been suspected of producing new types of dangerous influenza viruses that were highly infectious for humans. But pigs are no more responsible for this than we humans are, a new study shows.

Pigs can be infected with influenza viruses by birds and humans alike. It has therefore long been feared that avian and human flu viruses could become mixed in pigs and develop into new variants of dangerous flu viruses.

But a new study by DTU Veterinary – the National Veterinary Institute at the Technical University of Denmark – dispels those fears. The study, published in Virology Journal, shows that avian flu virus does not infect pigs more easily than, say, humans – in contrast with what previous studies have shown.

”My study shows that pigs are not necessarily the great flu-carriers they were once believed to be,” says Ramona Trebbien, a postdoc at DTU Veterinary, who conducted the study. “It also showed that new types of dangerous flu viruses can just as easily originate in humans or birds.”

Result disproves previous studies

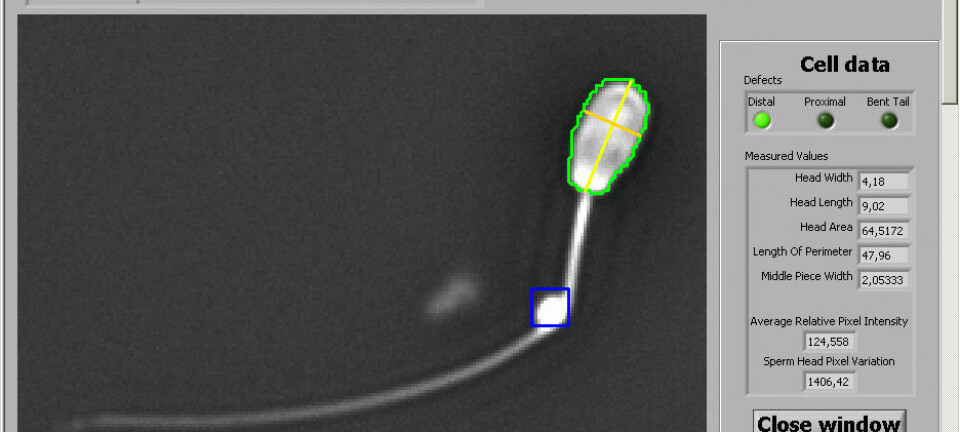

During an influenza infection, the virus binds to various molecules on the surface of the cells in the respiratory system tissue.

Trebbien’s study is the first of its kind to investigate all the parts of a pig’s respiratory passages: nasal mucous membranes, trachea, bronchi and various parts of the lungs – in an effort to map how pigs become infected with flu viruses.

Previous studies only investigated the pigs’ tracheae and concluded that avian flu could bind there. But Trebbien’s results show clearly that pigs do not have molecules in their nasal mucous membranes, trachea or bronchi, and that the avian flu virus do not bind to these parts of pigs’ respiratory passages; pigs only have such molecules deep inside their lungs, in the alveolar ducts, where oxygen is absorbed.

”This result surprised me,” she says. ”I had expected that my study would confirm and expand on the earlier studies, so being able to disprove the previous studies instead was quite a surprise.”

Pigs and humans are infected in the same way

Trebbien’s findings indicate that pigs are probably not as easily infected by avian flu virus as previously thought.

Trebbien explains that an avian influenza virus infection would still make the pig ill if the virus reaches the deeper parts of the lungs and causes deep-seated pneumonia.

”But that’s also how humans can be infected by avian flu virus.For that reason, pigs shouldn’t be regarded as a greater threat than humans in terms of developing new and possibly dangerous forms of flu virus.”

Other studies, however, show that chickens’ tracheae actually contain the molecule that human and swine flu viruses prefer. This means that chickens have a greater risk of being infected by human or swine flu viruses than pigs have of being infected by avian flu viruses.

”In other words, chickens are potential hosts – more so than pigs – where various types of influenza can mix and form new types of influenza,” she says.

Risk of new virus types still exists

The development of new influenza virus types, with a high rate of mortality and the same extent and speed of spreading as the ordinary flu virus that most of us are familiar with, has long been feared – not least since the outbreaks of avian flu, known as H5N1, in 2003 and swine flu, H1N1, in 2009.

But Trebbien’s study plays down that fear:

”It certainly removes an important factor – the pig – from the avian flu equation. That does not, however, eliminate the risk of a new and unknown type of flu virus breaking out. But it does mean that we can now with certainty ignore pigs and start looking for other potential hosts of influenza viruses.”

Read the article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Michael de Laine