Vietnamese farmers smell health risk of faeces

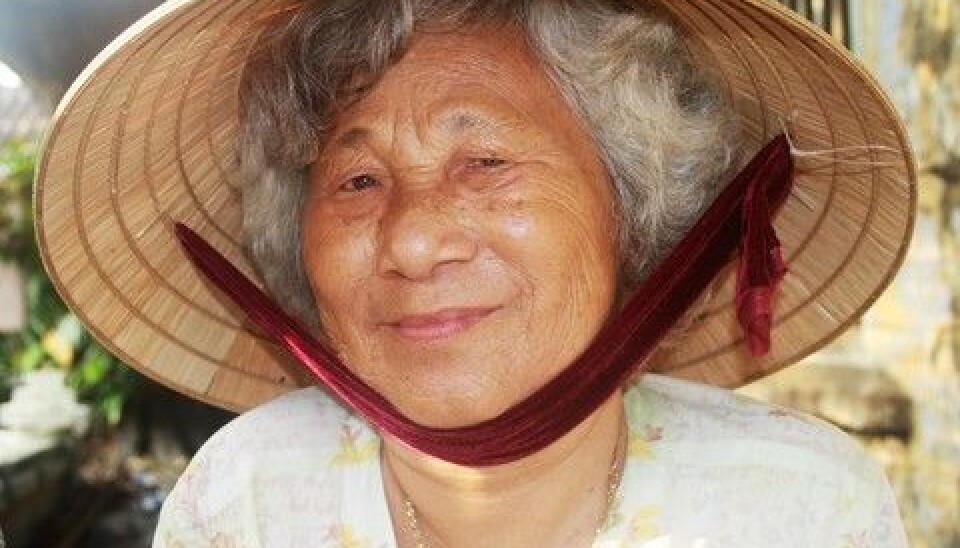

Vietnamese farmers fertilise the soil by spreading human excrement on the fields with their bare hands. But it is only the smell they believe to be a health risk.

Vietnamese farmers are convinced that the smell of faeces can make them ill. They spread human excrement on their fields with their bare hands and walk around in it in bare feet, but wear face masks to protect themselves from the smell.

Research projects supported by Danida, Denmark's development cooperation agency, have studied how people in countries like Vietnam think they become infected with gastrointestinal diseases. The aim of the research is to put sanitation and hygiene on the agenda in areas plagued by infectious diseases from human excrement.

"We have done well in ensuring access to clean drinking water in the world's developing countries. But progress is lacking in access to clean latrines and toilets," says Professor Anders Dalsgaard at the Department of Veterinary Disease Biology at the University of Copenhagen. Together with his colleagues at the Faculty of Health Sciences, he has conducted research into hygiene perception in Vietnam and Africa.

"Every year, there are many deaths and cases of diarrhoea because of poor hygiene. It is the handling of human faeces which spreads infectious agents such as salmonella and parasites."

Understanding the mindset

Naturally, we must provide clean drinking water, but we must also look at toilet hygiene conditions. Otherwise infectious diseases will continue to spread and kill many people.

Many farmers in northern Vietnam use human excrement as a fertiliser on their fields. The practice has some sense in it, since faeces contain plenty of nutrients which are beneficial to the growth of crops. But it needs to be handled properly to avoid the spreading of diseases.

In the western world, the importance of hand-washing to limit the infection risk from faeces is well understood. But in Vietnam, farmers protect themselves instead against the smell, because they believe it is the smell that makes them ill.

This is why Vietnamese farmers wear face masks when they handle faeces. At the same time, they walk around in bare feet and use their bare hands to spread the excrement on the fields.

"Before you can start changing the approach to hygiene, you need to understand how people perceive the risk of infection,” says Dalsgaard. "To change the behaviour of Vietnamese farmers first requires an understanding of their mindset. You can't just say to them that they must wash their hands and use gloves and boots, when they think the contagion comes from the air."

Odour-free interpreted as safe

Farmers in northern Vietnam often mix human excrement with rice husks and other organic material to turn it into a fertiliser before it is spread on the fields. When they do that, the obnoxious smell disappears and so the farmers consider the faeces to be safe. They spread it on their fields by hand without concern.

The lack of smell misleads them, however, since bacteria and other infectious agents, especially the eggs of the troublesome parasitic worm Ascaris, are still very much present and cause widespread disease.

Two different words for waste water

Generally speaking, smell has considerable significance for how waste products are dealt with in Vietnam – including the way in which farmers talk about polluted waste water.

When waste water is pumped onto the fields in urban areas, it is black and foul-smelling. But decomposition is rapid, and the smell disappears as the waste water turns green-brown.

"The Vietnamese have two different words for waste water, which frequently contains not only faeces but also hazardous substances from industry,” says Dalsgaard. "One of them is negative and is used for the black, foul-smelling waste water. The other is positive and is used for the green-brown waste water, which is odour-free and contains nutrients which serve as fertiliser for the crops."

The farmers move around in the rice fields without any protection, since they consider the water to be completely clean, he says.

Toilet trouble in Africa

It is not only the Vietnamese who are more concerned with the smell of faeces than handling it hygienically.

In some places in Africa, toilet hygiene conditions are so bad that people take their clothes off outside the toilet before using it. This behaviour originates from the belief that the smell sticks to their clothes, and that other people can smell it.

This results in people being in such a hurry when using the toilet that they often 'miss the target'. Such misdirected faeces constitute a considerable infection risk for subsequent users of the toilet.

"In Africa, there are major problems with toilets in schools which are very unhygienic. Girls especially avoid going to the toilet, and that is why many of them get urinary tract infections,” says Dalsgaard. "Toilets have to be built with technology that is adjusted to the conditions; otherwise it can have serious health consequences."

Improper disposal

In recent years, clean drinking water for developing countries has been a major focus area. This initiative should be followed by an increased focus on toilets, thinks Dalsgaard. Toilets should be built not to western standards, but according to the geographical and cultural challenges.

In Africa, for example, there are major problems with improper disposal of faeces. It is commonly the case that infected faeces are pumped into the sea close to the coast.

Unhygienic faeces management results in significant problems with infectious agents, since the faeces invariably come into contact with food, drinking water or children who play on polluted land.

Flying toilets

In other cases, people avoid using toilets because they are disgusting and smelly.

In some places, toilets do not exist at all. Instead people defecate into bags which they throw away – a health menace which has acquired the name of 'flying toilets'.

“When we think about the many people who die in the world's developing countries of diarrhoeal diseases, we primarily think of clean drinking water as the solution to their problems,” says Dalsgaard. “Naturally, we must provide clean drinking water, but we must also look at toilet hygiene conditions. Otherwise infectious diseases will continue to spread and kill many people.”

Read the article in Danish at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Nigel Mander