See where Greenland harbour porpoises travel

These tough small whales use large parts of the North Atlantic, swimming much further offshore and diving far deeper than previously expected.

A new study casts fresh light on the movement and diving behaviour of harbour porpoises in Greenland.

The study reveals how well adapted these porpoises are to the harsh subarctic environment of West Greenland--partly in their ability to move to the North Atlantic when conditions in West Greenland become too harsh in winter.

Harbour porpoises are widespread across the northern hemisphere and several studies have shown how well adapted they are to forage on local prey in any given area. Our study, however, reveals how porpoise are even more adaptable than first thought.

The study is part of my Ph.D. project and was conducted in collaboration with the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and Aarhus University, Denmark.

Read More: Meet ‘Mojn’, the ten million-year-old Danish whale

Using echo localisation to catch their prey

Porpoises do not attract much attention. But you might have seen the small, energetic whale in coastal areas. They have a characteristic sound, almost like a sneeze, that they make in the short moment before breaking the surface.

They use echo localisation, just like the narwhal, to locate and catch their prey.

Few people know that there is a population of porpoises living in the subarctic waters of Greenland and scientists do not much about them either. Many years ago, they were often bycatch of salmon fisheries, but that has since ceased. Today, only Inuit hunters are allowed to hunt porpoises in Greenland.

Read More: Bird senses can improve drone navigation

Spying on porpoises with satellite transmitters

Porpoise are frequently seen in West Greenland during summer, but we didn’t know where they go as the ice forms in winter. We thought that they simply moved along the ice edge, just a little further away from the continental shelf.

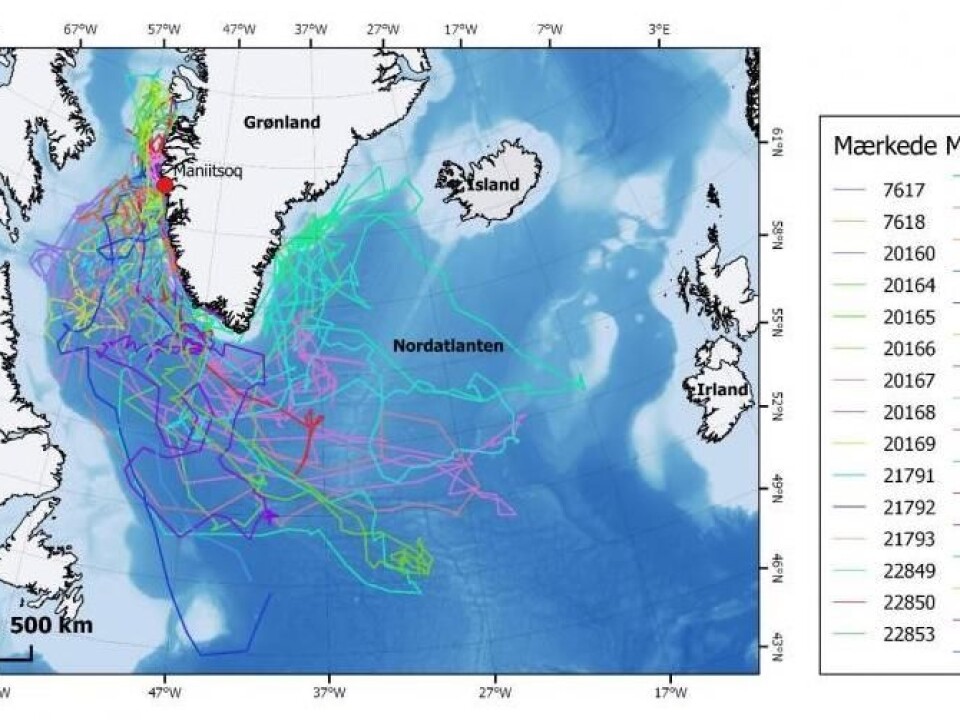

In our study, which has just been published in Marine Ecology Progress Series, we attached satellite transmitters to 30 porpoises so we could track their movements. This have given us a novel and unique insight in the activities of harbour porpoises from West Greenland.

Surprisingly, we saw that porpoises travel more than 10,000 kilometres, before remarkably returning to the very same place where they were tagged the previously year.

The porpoises travel up to 2,500 kilometres offshore from the tagging site where they swim in waters that reach 2,000 to 3,000 metres deep.

We also saw that porpoises were able to dive down to 400 metres depth to forage for food.

Read More: Inuit hunted whales 4,000 years ago

Tough harbour porpoises thrive under harsh conditions

So, despite what scientists had thought, porpoises from West Greenland are in their element when located far offshore, performing deep dives.

Our results show that porpoises from West Greenland live in a more challenging environment compared to their European cousins. Winter sea ice forces these small whales to move into ice-free areas in order to find suitable prey such as fish and squids.

When the porpoises move offshore into the North Atlantic, prey becomes scarcer, forcing the porpoises to forage more extensively and increase their swimming speed in order to fulfil their demand for prey.

Read More: Hear a whale calf speak to its mother

Built for survival

Porpoises are small and agile and very hard to spot in that brief moment before they break the sea surface. This probably explains why scientists have only just described their extreme offshore winter movement into the open ocean.

The porpoises return to West Greenland in summer, and they even find their way back to the very same area that they were tagged in the year before. Here, they mate and give birth.

As the name suggests, harbour porpoises are coastal animals. However, this study now documents how they apparently thrive in offshore waters, far away from the coast.

This opportunistic behaviour should help the harbour porpoise deal with the changing conditions imposed by climate change.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

This article is based on partial results from my Ph.D. studies at Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and Aarhus University. The study can be found here. If you have any questions, you are welcome to contact me by following the links below.

Translated by: Nynne Elmelund Lemming