Hear a whale calf speak to its mother

Scientists have recorded conversations between mother humpback whales and their calves for the first time. The recording shows how young whales “whisper” to their mothers so that potential predators cannot hear them.

Professor Peter Teglberg Madsen from Aarhus University, Denmark, stands on a motor boat in Exmouth Gulf, West Australia.

He is holding a nine metre-long stick, which he aims at a humpback whale calf, which is swimming just beneath the surface of the water with its mother.

When the tip of the stick touches the calf, it attaches a suction cup to the young whale’s skin. The suction cup contains a hi-tech tag, which enables Madsen to listen in on the young whale’s conversations and track its movement.

As the whales swim away from the boat, the scientists celebrate. This little whale is the first to be tagged in this way, and will allow the scientists to map how the whales communicate with their mothers.

Read More: Tracking the migrations of humpback whales

Young whales “whisper” to their mothers

It is now almost three years since Madsen and his colleagues went to Australia to tag the whales. In all, they tagged ten animals and they have now published their results.

The study shows that young whales “whisper” when the communicate with their mothers—probably to avoid being overheard by potential predators.

“We discovered that the calves don’t make a lot of noise—they use very short and weak sounds. We think that it’s because they only intend for their mother to hear them,” says lead-author Simone Videsen, research assistant at Aarhus University.

“There’s lots of killer whales in the area who are known to hunt calves and eat them. So it makes sense that calves make very quiet calls so that they’re not overheard by killer whales,” she says.

Read More: How much man made noise can the marine environment withstand?

Use sound to stick together

Scientists have studied communication of male whales before and it is relatively well understood. They are famous for their loud, catchy songs, totally unlike the soft, quiet song of the young whales.

The new study presents the first audio of whale calves and provides new insights into their behaviour.

“The recording shows that the whales typically make peaceful sounds when the whales are swimming. This suggests that the sound helps mother and calf to stay together in the turbid waters of Exmouth Gulf. We heard many rubbing noises that sounded like two balloons being rubbed together. We think that’s because the calf rubs against its mother when it wants to suckle,” says Videsen.

Hear a baby humpback whale speaking to its mother.

New insights into the lives of young humpback whales

Lee Miller studies whale communication at the Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark. The hi-tech tagging apparatus used in the study provides new insights into the whales’ early lives, he says.

“It’s an excellent study. They tag the whales with a very advanced piece of equipment that gives us a very detailed picture of what goes on between a mother and her young. They can do this without disturbing the whales too much and this is new,” says Miller, who was not involved in the new study.

In addition to recording the whale song, the tag also tracks their depth and how they move around.

“It shows that the young whales suckle at a depth of around 10 metres. We wouldn’t be able to see that without tags. We can observe them suckling at the surface, but it’s new to show that they also suckle while at depth,” he says.

“They also see that both the mother and the young calf stay very still while they suckle. There’s no movement, unlike porpoises, for example, which swim round and round while they suckle,” says Miller.

Read More: Meet ‘Mojn’, the ten million-year-old Danish whale

Young whales are slow eaters

The new study also showed that the young whales spent a lot of their time feeding. This makes a lot of sense as the whales need to fatten up quickly for their long trip to the Antarctic, says Videsen.

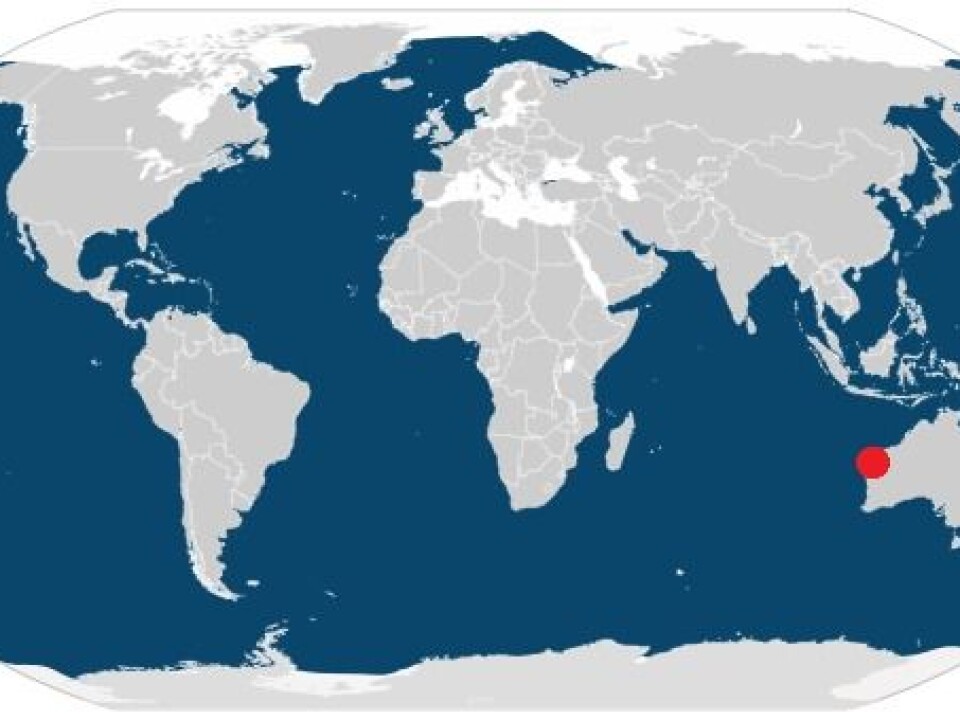

After being born in the tropical waters of Australia, they embark on a long journey down to the Antarctica.

“Humpback whales spend the summer in the Antarctic or the Arctic, where they search for food and put on weight. But in the winter, they head back to tropical regions to breed and feed their young. When the calves are born, the whales swim back to the Antarctic. The journey from Australia is more than 8,000 kilometres, so the calves need to fatten up to cope with the journey,” says Videsen.

In the Antarctic the whales gorge themselves on krill, mackerel, herrings, and other small fish that swim into their open mouths. But when the whales head back to the tropics, the mother does not eat at all, says Videsen.

“The mother makes sure that her calf feeds and puts on weight, but she herself doesn’t eat while they migrate. So it makes sense that she stays still while the calf feeds, to save her energy,” says Videsen.

Read More: Culture is a strong evolutionary drive among killer whales

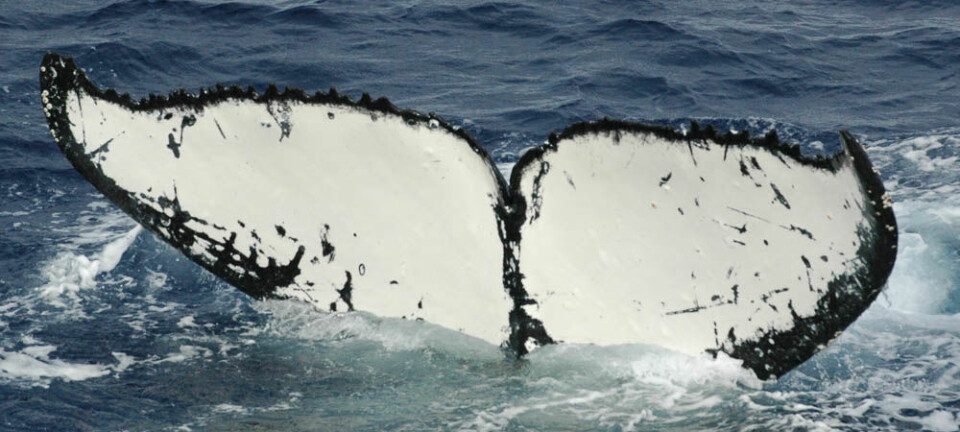

A humpback whale mother and calf swimming in Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia. (Video: Frederik Christiansen /Aarhus University)

---------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex