Inuit hunted whales 4,000 years ago

Fossil DNA from kitchen midden deposits reveal masses of whale blubber, leading scientists to believe that Greenlanders hunted the ocean’s giants 4,000 years before anyone else.

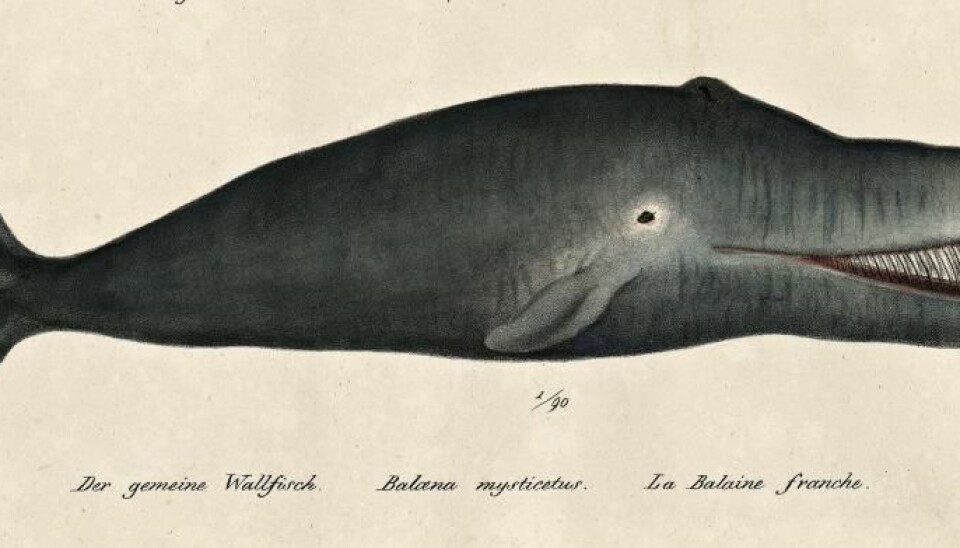

The Bowhead whale has long been the favourite catch among whalers, and a new study suggests that this preference has been around for thousands of years.

The study analysed 4,000-years-old fossil DNA from ancient kitchen middens on Greenland. The analysis revealed traces of bowhead whale, which indicates that the first Greenlanders were already hunting the giant animal back then.

“The most sensational discovery is without doubt that we find high amounts of DNA from bowhead whales. It’s new and exciting, because when you compare it with bone fragments from the same kitchen middens, you never see whale bones,” says lead-author Frederik Seersholm, who was employed by the Center for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark when he carried out the research.

The results are published in Nature Communications.

New application of fossil DNA

The study gives a detailed picture of how the Inuit lived and what they lived on, and perhaps even more remarkably, it does so with nothing more than the DNA contained in a few grams of soil.

“This is a really effective tool and we show that the method works. I think that we can use this for much more. We’ve only just begun,” says project leader Anders Johannes Hansen from the Center for GeoGenetics.

Arctic archaeologist Jens Fog Jensen from the Natural History Museum of Denmark agrees. He did not take part in the new study.

“The paper presents ground breaking new methods. Investigations of DNA from layers of earth in an old settlement, and the quantification of DNA from different animal species in particular, represents an entirely new alternative way of illuminating this prehistoric resource-economy,” says Fog Jensen.

“Fossil DNA is a new source of information for these type of questions, and the application of these methods will no doubt result in many new insights into prehistoric animal life,” he says.

Norsemen and Inuit kitchen waste was rich in DNA

The new results are the culmination of Seersholm studies for his Ph.D. thesis.

“It started as a much smaller study, where I just wanted to see what came out of the DNA sequencing in a single kitchen midden from an old Viking farm in Greenland,” says Seersholm.

But then they discovered huge amounts of DNA in the 1,000 year-old soil samples.

So Seersholm decided to expand the study to other settlements that covered the three other waves of immigration and settlement of Greenland--Saqqaq, Dorset and Thule--which date back 4,000 years.

Bones reveal the Inuit diet

Among the settlements studied was a site in Disko Bay, on Greenland’s west coast, made famous by the discovery of the Saqqaq culture, which is the earliest known culture in Greenland.

Professor Morten Meldgaard from the Center for GeoGenetics and the University of Greenland excavated the site in the 1980s.

It was his father who discovered the existence of the Saqqaq culture in the 1950s. “So it’s a bit fun to think of this as something that’s been passed down to me,” says Meldgaard.

“Back in the 1980s it took many years to go through the bone material and find out what people lived off and what food was on the menu in these settlements,” he says.

When the scientists mapped all of the fossil DNA in the soil samples, they discovered DNA from many different animals, including reindeer, narwhal, walrus, and the bowhead whale--even though there were no bones fragments preserved from any of these species.

In the Norse settlement, they discovered evidence of goat, sheep, and cow DNA.

Bowhead whale was firmly on the Inuit menu

The scientists calculated how many of these animals were represented in the kitchen midden deposits according to the individual DNA sequences.

“We’ve checked it against the earlier studies and we can see that it’s consistent with the biomass [calculated in previous studies],” says Hansen.

Their calculations revealed that the bowhead whale was the most important source of food for the Saqqaq culture.

“You can just imagine that the settlements were powered by blubber,” says Hansen.

Did the Inuit hunt whales?

It is possible that the Inuit scavenged the meat from dead whale carcasses, but it is unlikely, say the scientists behind the study.

“Some think that these people couldn’t have hunted whales, but others, like me, think that it’s entirely plausible,” says Meldgaard.

Archaeologists have discovered very few harpoons and lances large enough to bring down such whale.

There are, however, several factors that make early whale hunting a plausible scenario.

To begin with, Disko Bay was teeming with bowhead whales during the Saqqaq culture.

“When these people arrived in Greenland, 5,000 years ago, there were no people here and the animals had no predators. The Inuit arrived in a paradise and the animals simply came and went--and there were a lot of them. They probably lived well during the 1,000 years they were there,” says Meldgaard.

And what’s more, the whales were probably easy catch.

The large animals are mild natured and often venture into shallow waters, and they have so much blubber that they float when they die.

Hunters snagged sleeping whales

The Inuit hunters probably knew that the whales slept at the ocean surface. Historical sources show that Inuit hunters knew how best to snag a sleeping whale at least 200 years ago--a single spear through the heart, just behind the flipper.

Other sources describe the use of poison during the 1700s, says Meldgaard.

In the Fauna Groenlandica, Otto Fabricus described how infection brought about by a cut from an arrow could drive a whale inland, allowing hunters to effectively kill it without wrestling with the giant animal.

“We’d like to advance the debate about what it takes to bring down a whale. It wouldn’t be the first time that we’d underestimated native peoples’ capabilities,” says Seersholm.

“Personally, I don’t think that it’s so farfetched to think that paleo-Inuit were able to bring down a Bowhead whale themselves,” he says.

-------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex