Can you spot the walrus?

GREENLAND: Scientists in Greenland are developing fast and efficient ways to monitor walrus populations in remote locations using high-resolution satellite images. If successful, the technique could be rolled out to other species.

Keeping track of animal populations in Greenland is not an easy task: the country is vast and largely covered in ice and aerial surveys are expensive and time consuming.

So scientists in Greenland have begun using high-resolution satellite images to track populations of larger animals--starting with the walrus. The project is still in the early stages, but results so far look promising. If successful, then it could be rolled out for many other species throughout the Arctic.

“Spotting walruses is costly. You need to travel to remote places and observe them from an aeroplane and fly along a number of tracks across a large area,” says Karl Zinglersen, a remote sensing specialist from the Department of Environment and Mineral Resources at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, Nuuk, who is involved in the new project.

“So we’re trying to see how far we can go with high detail satellite imagery to spot walruses, just as you would do in an aeroplane but from the comfort of your desk,” says Zinglersen.

Walrus spotting with Google Earth

Walruses are the ideal animal to test the new method. Not only are they big enough to be imaged from space--you can even spot them on Google Earth--but there are certain locations around Greenland where you are almost guaranteed to find them.

“We chose to focus on walruses first because, although they are marine animals who spend a lot of time in the sea, they also go onshore and onto the ice after feeding to rest and build up fat for the winter time,” says Zinglersen.

Zinglersen and his colleague Kirsty Langley, a remote sensing specialist from the Greenland Survey, ASIAQ, chose three sites where they knew there was a good chance of finding walruses at a particular time of year: Sandøen (Sand Island, north east Greenland), Little Snowy Point (a sandy beach in Danmarkshavn, east Greenland), and Wolstenholm Fjord (near to Thule airbase in north west Greenland).

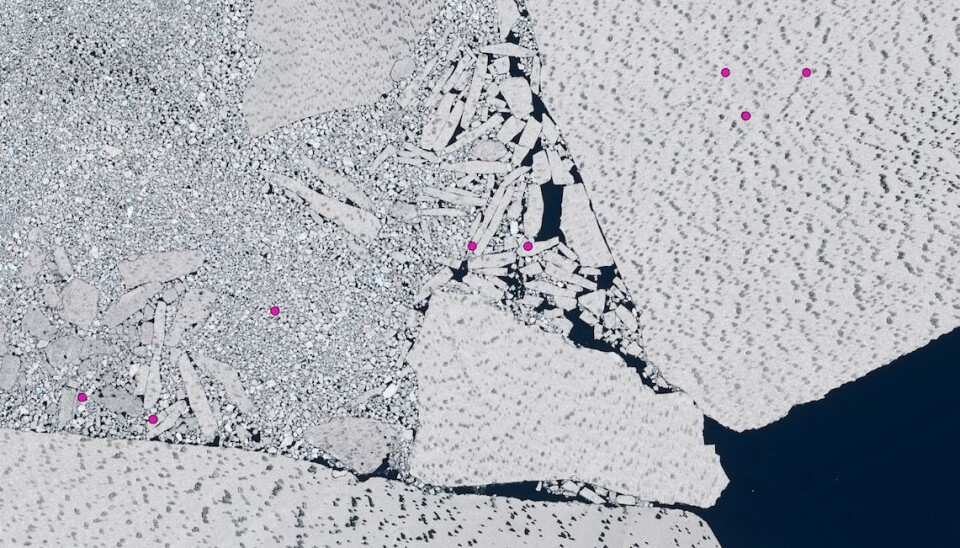

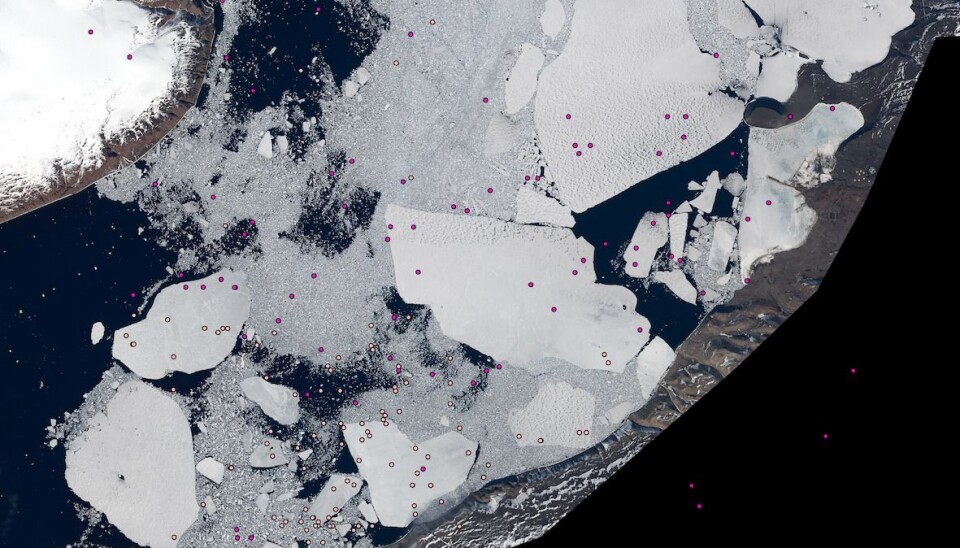

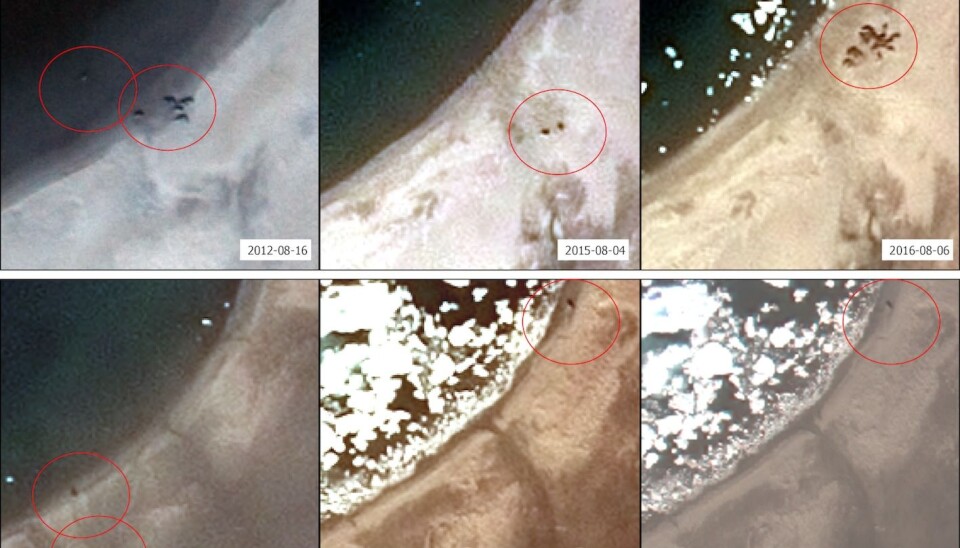

Try it yourself: zoom in and move around this satellite image taken in 2012 of Sand Island, north east Greenland, and see if you can spot the walrus. (Image. Google Earth)

Quick and reliable method

While it is possible to simply count the walrus in an image, Zinglersen wanted to make the method as quick and reliable as possible.

For this he needs to compare a set of high-resolution satellite images (where each pixel represents as little as 30 centimetres) covering the same spot over a number of days.

“The images are not just photos. Each pixel contains data, so if the number in a pixel changes in a set of images, we can calculate the difference between them,” says Zinglersen.

He uses computer algorithms to quickly identify the differences between the images. This way he can identify the pixels that are most likely to be mobile walruses, and not for example, stationary rocks or a dark shadow.

Another piece of software then groups these walrus pixels together and estimates how many walrus there are, according to a number of rules that Zinglersen has set beforehand.

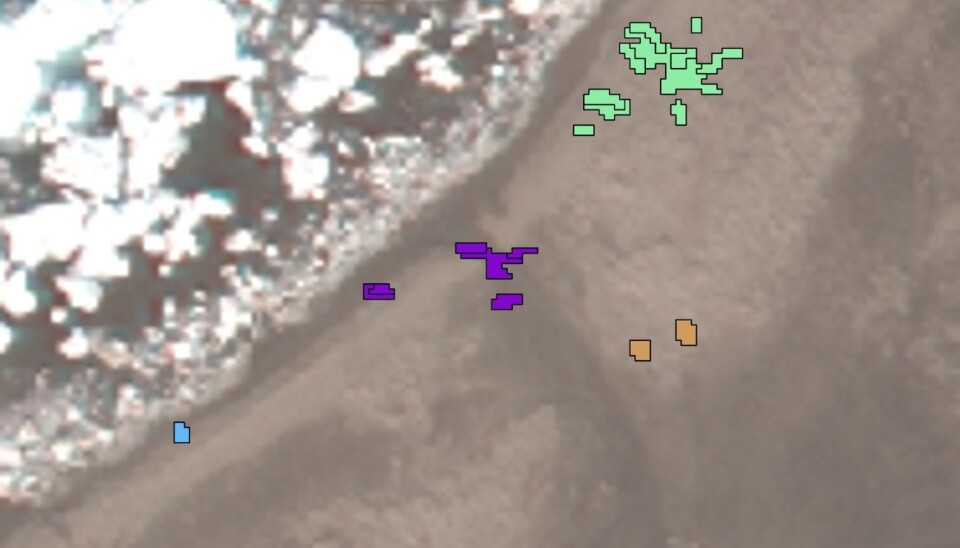

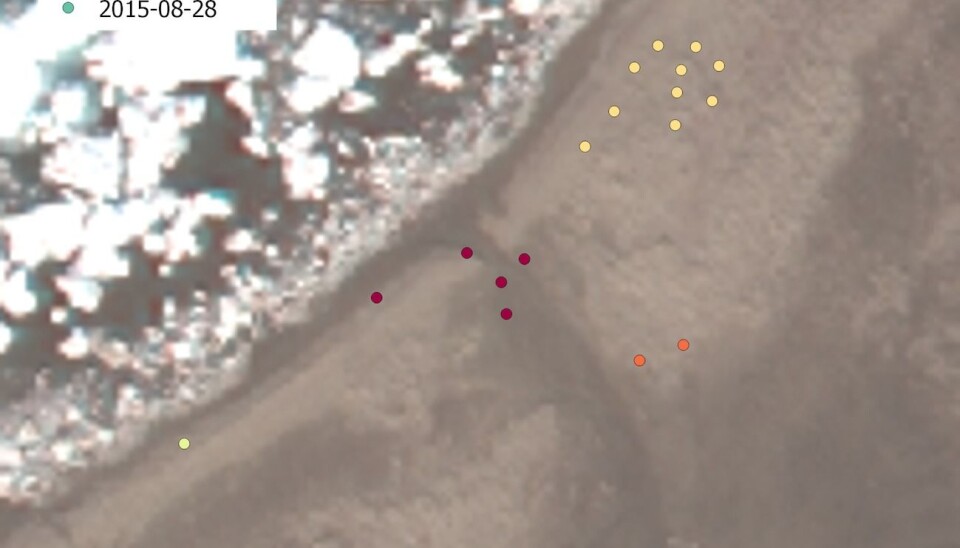

“Using false colouring we can then pick out the walrus and distinguish each individual pixel or look at a group of pixels to distinguish the differences from one group to another over a few days,” says Zinglersen.

You can see some examples of these images in the gallery at the top of this article.

Works on sand, but problems on ice

While the method seems to be working well on Sand Island and Danmarkshavn, they have had less success on the fjord ice in Thule, north west Greenland.

Here, they compared a satellite image of the fjord ice with location data from trackers that had been attached to a number of walrus in the area as part of a separate project. But even though the trackers indicated that the ice should be teeming with walruses, they were unable to spot a single one in the satellite images.

“We haven’t analysed them in detail yet, but still, we should see them. If you see them on sand, then we should be also be able to see them on ice,” says Zinglersen, adding that the walrus have most likely just moved on before the satellite images were taken.

Automated image analysis faster than aerial surveys

While the new method is certainly less time consuming than traditional aerial surveys, Zinglersen is not yet sure whether it will be a cost-effective alternative.

“These satellite images are very costly. Of course the air-campaigns are costly too, so we don’t yet know if this will be more cost-effective. But we’ll find out,” he says.

If the answer is positive then the method could eventually be used to monitor other species.

“Musk Ox would be good to monitor this way, and over a large area. The only limitation is that the animal needs to be bigger than the pixel size. And it needs to be quite a bit bigger, so you can see an individual animal in a group pixels. So a couple of metres in size,” he says.