Killer whales and walruses more closely related to wolves than each other

New study shows how some animals ended up looking very similar yet share almost none of the same genetic mutations.

New research shows that even though many of the mammals that live in the sea look similar, they are not closely related.

Animals moved from the sea to earth around 500 million years ago. 300 million years later the first mammals emerged.

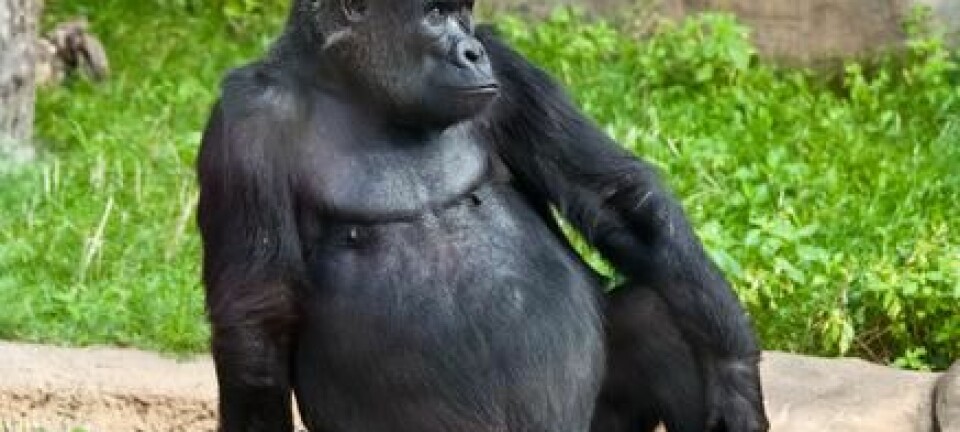

Over the next million years some of these animals gradually returned to the sea, creating a variety of adapted species including killer whales, walruses, and manatees.

They represent a classic example of convergent evolution, shows a new study recently published in Nature Genetics.

Marine mammals are not closely related

Despite the many similarities between killer whales, walruses, and manatees, they are -- as surprising as it may sound -- more closely related to wolves, cows, and elephants than to each other.

They have adapted to the sea in many of the same ways, but they do not share the same immediate ancestors.

A new study shows how the genes of these marine mammals have evolved and become similar in shape -- although they are genetically different.

“In many ways the research can be used to understand evolution better,” says lead author Andrew Foote, postdoc at the Centre for GeoGenetics at Copenhagen University. “From the outside these animals look alike, but they are radically different on a genetic level.”

Animals evolved in the same ways

The study is concerned with the concept of convergent evolution.

Convergent evolution means that two different species -- which are distantly related -- develop the same traits to adapt to a particular environment.

For marine mammals this means, for example, that the killer whale, manatee, and walrus each have, over millions of years, transformed their hind legs into a tail for swimming.

Another striking example of convergent evolution is that both insects, birds, and some mammals have developed wings for flying.

Foote wanted to investigate whether convergent evolution can be traced in the genes. The question he sought to answer was if the different species had walked down the same genetic paths to develop their unique adaptions?

“This would make a lot of sense,” says Foote.

However, the study shows that the marine mammals have used completely different genes to develop similar adaptions.

“Most often, convergent evolution follows different genetic paths to achieve the same physiological adaptions in a given environment,” he says.

Only 15 genes evolved similarly

To his great surprise Foote only found 15 genes that seemed to have undergone convergent evolution -- that is, where all three species had similar changes in the same genes.

These changes were found in genes associated with bone density, blubber, ear bone structure, blood thickness, and blood coagulation.

Furthermore, the researchers found no evidence that tail and fins were created in the same way.

"We were certain that for the tail and fins we'd see convergent evolution in the same genes, however, we did not,” says Foote. “The animals had found other genetic pathways to achieve the same physiological result.”

Support from the scientific community

Professor Mikkel Heide Schierup from Bioinformatics Research Centre at Aarhus Universitet studies genetics and evolution. He did not participate in the study, but he has read it and is impressed with the results.

“It's exciting," says Schierup. "It's important for us to find out how many different ways organisms can adapt genetically."

-----------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Louisa Field