How the Nazis abused the history of runes

A brooch inscribed with runes was found in a field in Denmark during the Second World War and tells a story of the use and abuse of runic writing during some of the darkest moments in our history.

In 1944, a conscientious citizen told the National Museum of Denmark that he had found something at an airfield in Værløse.

At that time, German occupying forces were establishing a military installation in the area and during the construction they unearthed a skeleton and various pieces of jewelry a metre below ground level.

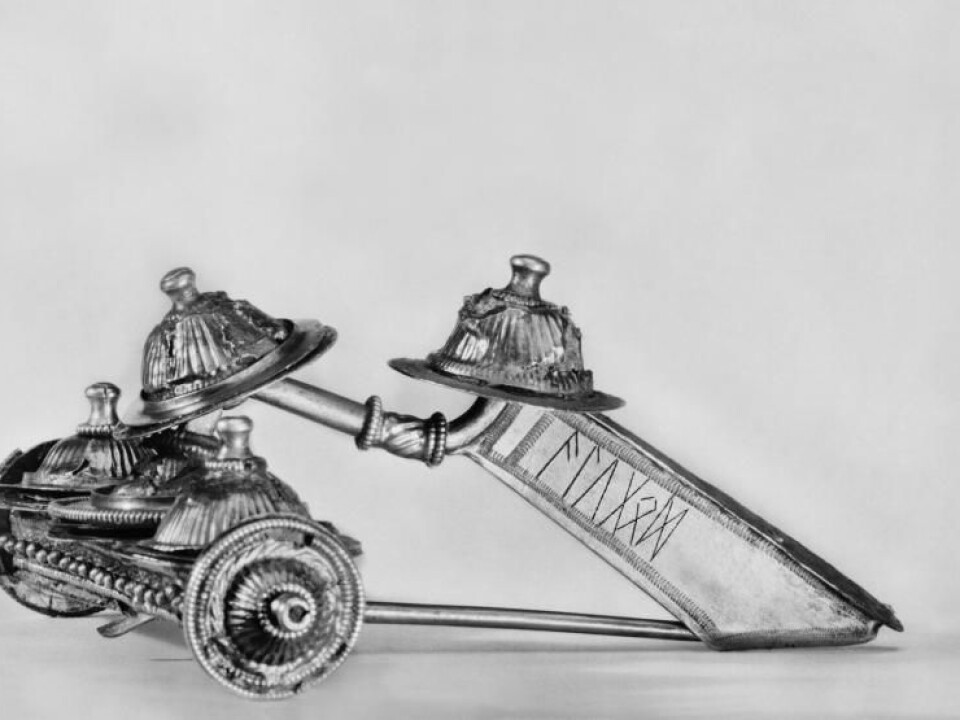

After a struggle with the German authorities, the museum inspector, C.L. Vebæk (1913-1994), finally gained access to the site. He found skeletal remains and antique objects scattered randomly at the scene, including a brooch of the type that archeologists call a rosette fibula.

Read More: Unique Viking runes discovered in Denmark

Alugod’s jewelry bore an unfortunate swastika

On one side of the brooch, the name ‘Alugod’ was carved in runes alongside a swastika: the ancient sun symbol that was common throughout Europe and experienced an unfortunate renaissance in the 1930s as the symbol of The Third Reich.

The discovery was not reported by Danish newspapers until March 1945 but none of the media reports mentioned the swastika. And it was also skilfully removed from the photos held by the National Museum of Denmark.

Not only was the now hated Nazi symbol not mentioned in the media reports, but it was erased entirely from history. And there were good reasons for that.

Read More: Isolated people in Sweden only stopped using runes 100 years ago

The Nazis’ distorted history

The censored reporting of the Værløse brooch was a natural backlash to the propaganda of the Nazis.

Central to Nazi ideology was the belief that the Germanic race was superior to all others. They thought that the roots of European culture were to be found in the Nordic countries and that culture was created by the Germanic or Nordic people. This is where archaeology and runology played an important role.

Historians know that Mediterranean alphabets inspired the later runic alphabet, known as furthark, after the first six letters: f, u, th, a, r, and k.

But this posed a problem for the Nazis who claimed that the Germanic runes were the first known alphabet. So, they simply rewrote history: They decided that the Germanic runic alphabet did not follow from the Mediterranean alphabets at all. Rather, furthark, they claimed, was the first alphabet from which all others descended.

Read More: Thousands of objects discovered in Scandinavia’s first Viking city

‘Nazi runes’ were part of a terrifying ideology

In Nazi ideology, the runes took on an entirely new meaning, well beyond simple characters for writing. Every single rune had its own meaning, and the Nazis believed that this meaning lay hidden in the soul of the Germanic people.

The best known Nazi rune is perhaps the s-rune, originally known as the sun rune. In 1929, it was renamed as the ‘Siegrune’ (the victory rune) and became the symbol of Hitler’s SS (Schutzstaffel).

The o-rune, whose name was *ōðila – meaning inheritance, was used as a symbol of ‘Blut und Boden’ (blood and soil), and the t-rune as a symbol of war and struggle, after the god of war, Tyr. It became popular in the Nazi youth organisation Hitlerjugend. The R-rune became the symbol of either life or death depending on whether the diagonal lines were facing up or down.

The consequences of the Nazi’s portrayal of themselves as a supreme race are well known. And today, all symbols resembling Nazi symbols are forbidden in the German constitution.

Read More: How young people today view the Second World War

Hold on to identity – but learn from history

Neo-Nazi groups still use the runes as symbols today, but they have also acquired a different role.

In Denmark, runes have become an important part of the country’s national identity and commonly appear in comic strips, TV shows, and even on the jerseys of the both the men’s and women’s national football teams.

Denmark have drawn inspiration from runes as national symbols, which can help maintain a sense of identity and community.

Ultimately, the abuse of runic writing may become a mere footnote in their broader history. Nonetheless, we should also learn from this history to prevent such misuse in the future.

---------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

This article is based on ‘Rigets runer’ by Lisbeth Imer which is part of the series ‘100 danmarkshistorier’ by Aarhus University Press.

Translated by: Frederik Appel Olsen