How young people today view the Second World War

Danes, German, and Finnish youth all see the Second World War as an important historical event. But that is where the similarity ends.

“The long shadow after a difficult past.”

This is the almost poetic title of a recent study describing how Danish, German and Finnish youth, perceive the events of the Second World War.

The study leaves no doubt that they consider the war to be the most important event of the 20th century. However, there are big differences between the ‘long shadows’ it cast for young people today in each of the three countries.

“Danish and Finnish youth generally have a narrow, national view of the Second World War. German youth are far more aware of the consequences of the war in the rest of Europe,” says Carsten Yndigegn, and associate professor at the Department for Political Science and Public Administration at the University of Southern Denmark, and one of the authors of the new study published in the Journal of Youth Studies.

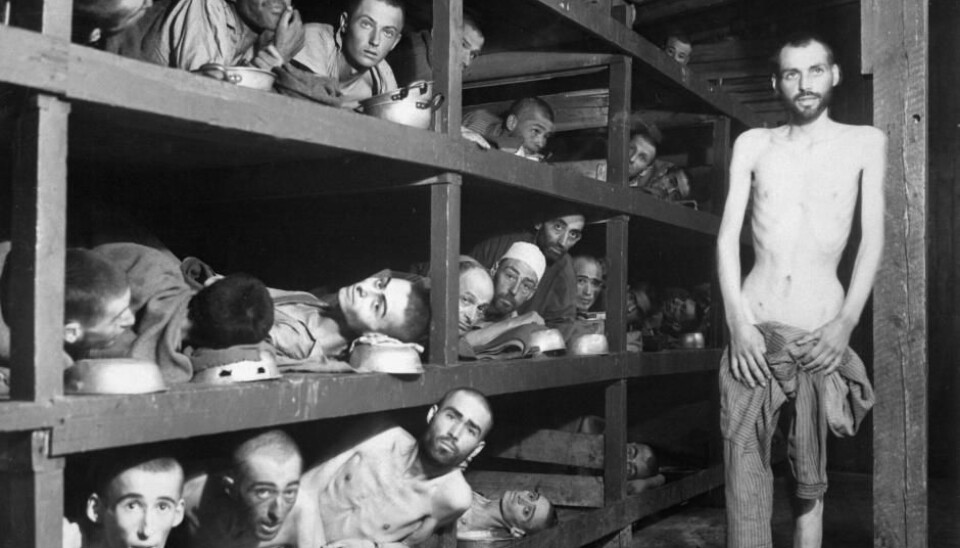

Read More: Soviet prisoners of war in Second World War – nameless, until now

The war still casts a shadow

The young participants in the study are between 16 and 25 years old and thus many generations removed from the war that ravaged large parts of the world between 1939 and 1945.

Nonetheless, the war is present and meaningful to the young study participants.

“Many of the young people have inherited a memory of the [war] from their family. This is true in Denmark, Germany, and Finland. So many young people are still actively aware of the war,” says Yndigegn.

In Denmark, it is not the Holocaust, the Invasion of Normandy, or the use of atomic weapons in Japan that make the strongest impression.

“Danish youth had a very nationalistic approach to the Second World War. They focussed heavily on the resistance movement in Denmark and they expressed a fascination and respect for resistance fighters. In that respect, the Danish youth have a more positive and heroic view of the war than German youth,” says Yndigegn.

Read More: How Hitler decided to launch the largest bike theft in Denmark’s history

Danish resistance fighters seen as heroes

The Danish youth’s heroic take of the war in many ways reflects the memories of the generations before them, says Anette Warring from Roskilde University. She was not involved in the study but studies collective memories and interpretation of history.

Her own research has shown how a post-war collective memory developed in Denmark. In this narrative, the country was among those resisting Nazi occupation and the resistance fighters are the heroes of the story.

However, it is almost forgotten how many Danes collaborated with the occupying German forces or even signed up to fight for the Germans, says Warring.

“Young people’s view of war largely follows the dominant recollection of the war as we know it from adults. It’s a story, where in the war, the resistance movement maintains an unchallenged position as the good guys and the ethical counterbalance to the war ,” she says.

Read More: Sexual offences increased in Denmark during the Second World War

Nuance passes them by

The collective memory of occupation in Denmark has become more nuanced in recent years, but there were few traces of this among the young people in the study, says Warring.

The common narrative has shifted to include for example, Danish Nazis, those who volunteered for the German war effort and Danish women having intimate relations with the occupying German soldiers.

“For many years they had been marginalised and excluded from the common national memory of the war. But in recent years it has become more nuanced, so that the memory of occupation is not only about the resistance. It’s surprising that there is no trace of this among the young people in the study,” says Warring.

Warring is also surprised that neither the Holocaust nor Denmark’s collaboration policy with Germany ranks higher in the awareness of the Second World War.

Read More: Are facts about women in war oversimplified?

Finnish youth view the Soviet Union as the enemy

Finnish youth also took a very nationalistic approach to the Second World War. In their narrative, Finnish alliance with Nazi countries between 1941 and 1944 was suppressed.

“Finnish youth largely did not think that Finland was originally allied with Germany. Rather they focussed more on the things they considered to be heroic, such as efforts of Finnish veterans in the Winter Wars when Finland fought the Soviet Union,” says Yndigegn.

“Here, the Finnish youth’s memories resemble somewhat those of Danish youth, which focus on the positive and heroic side, [while overlooking the] not so positive,” he says.

While both Danish and Finnish youth have a national take on the Second World War, their image of their enemy differs. Danish youth view the Germans as the enemy, while in Finland it is primarily the Soviet Union.

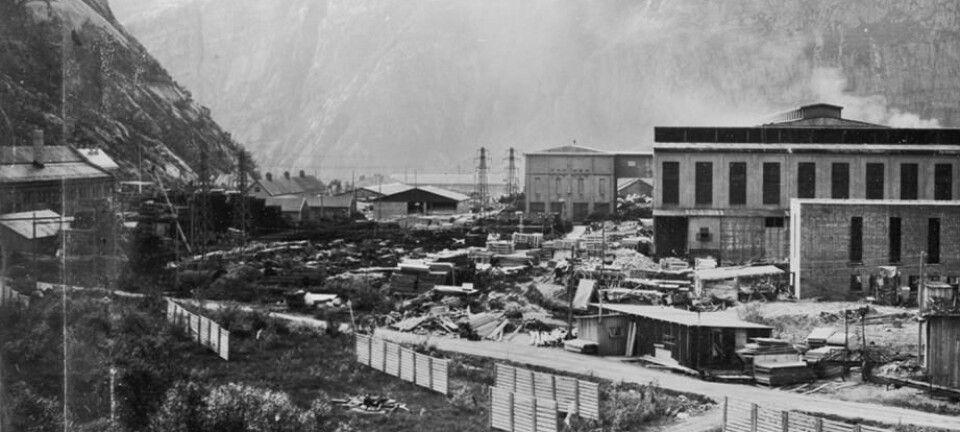

Read More: Norwegian industry complied with German war efforts

German youth have an international perspective

In Germany, the young participants in the survey were well aware that their country bears the responsibility of the war and Nazi crimes.

“German youth are very clear that their country led the world to war, not just in Europe but also beyond. They have no doubt what the Second World War was about. But you also begin to see that young people want to move forward. Many of them expressed that they cannot personally bear the blame for what happened in the past, long before they were born,” says Yndigegn.

“German youth don’t neglect or explain away the Holocaust or Germany’s responsibility as the aggressor in the war. It’s more that they don’t think that they should personally keep feeling guilty about it,” he says.

Read More: Uncovered First World War documents reveal widespread state censorship

Do German youth feel guilty?

A somewhat different portrait of the guilt of young Germans was painted in the book “Opa war kein Nazi” (Grandpa was not a Nazi), published in 2001, says Warring.

“The survey is a bit older, but it showed that three out of five young Germans felt guilty about Nazism. It’s surprising that they have not included the results of that study in this new study and discussed why they reach such different conclusions,” she says.

The same German study showed that even though young Germans did not deny their national history, their own family history was a different story.

“German youth had a very factual knowledge of Nazi crimes and German responsibility. It was a cognitive knowledge, which they used in the context of school. But when they had to explain what their grandparents did during the war, it looked different. If you were to believe all of the interviewees’ answers to questions about their grandparents, then it would mean that there were no Nazis in Germany,” says Warring.

Read More: Nazis used own laws on German-Norwegian homosexuals

German youth idealise their grandparents

The German youth had “forgotten” their own family’s part in the war. While their grandparents for example, may well have told their children and grandchildren that they had refused to hide prisoners of war during the war, the story was eventually changed to one where their grandparents had hidden and helped prisoners of war, says Warring.

“There was a kind of cumulative heroism. That is, the grandparents became bigger and bigger heroes as their narrative was recalled by the following generations. Of course it’s difficult to see your beloved Grandparents as accomplices or passive accomplices in Nazi crimes,” she says.

This displacement of ideas occurred despite the fact that German school policy placed a deliberate focus on condemnation of Nazi crimes and public responsibility, says Warring.

“It goes to show that if you just throw facts at people, then history will not be connected with an emotional understanding of how such a brutal regime could develop in German society,” she says.

Read More: Denmark’s Cold War struggle for scientific control of Greenland

Relying more on family than school

In both Germany and Finland, most young people also expressed more trust in the family’s story of war than official representations.

German and Finnish youth were sceptical about the version of events recorded in the history books, presented during their school days. They trusted their parents’ and grandparents’ accounts more.

“We didn’t see the same problem in Danish youth who trusted both the family’s stories and their school classes,” says Yndigegn.

Both Yndigegn and Warring think that Danish youth accept official representations of the war more easily, since their relationship and understanding of the war is less conflict ridden than in Germany or Finland.

“In Denmark there were many conflicts over the interpretation of the war, including when it comes to the collaboration policy. But it’s nothing compared to the dramatically different historical interpretation in Germany and Finland,” says Warring.

“The Danish memory of the German occupation is characterized by more consensus and I think that gives a greater degree of confidence in the official stories of the war,” she says.

------------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex