The Greenland ice sheet will survive global warming

The inland ice will not disappear even though Earth’s climate is getting warmer. But the higher temperatures will lead to substantial melting of Antarctica, new study finds.

Global warming will not cause the Greenland ice sheet to melt away as previously thought. At least not for the next 4,000 years.

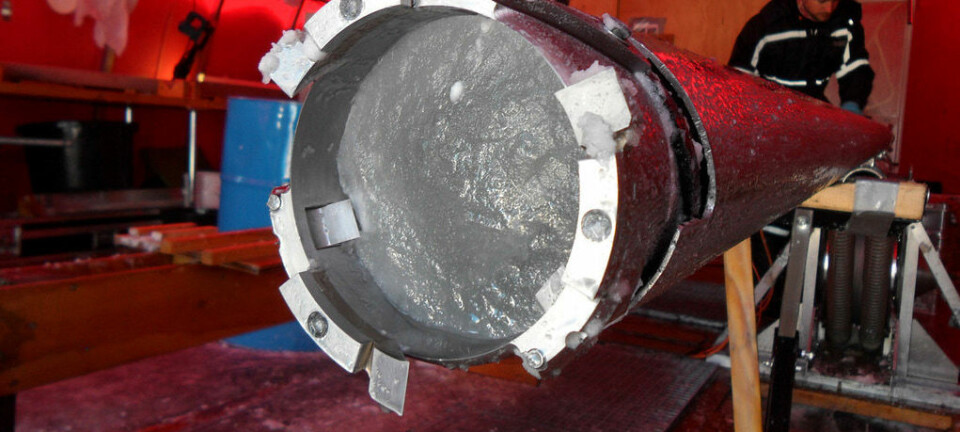

This is the conclusion of a comprehensive study of a 2.537-metre long ice core, which an international research team has drilled up from the ice sheet.

The ice core contains detailed information about how the global climate changed in the second-to-latest interglacial period of the current Ice Age, known as the Eemian, which was warmer than the current interglacial period.

Studying the ice core can give an indication of how conditions on Earth will evolve in the long term as the planet is getting warmer.

“Our analyses of the ice core show that as early as at the beginning of the Eemian period, temperatures on Earth were 8 degrees warmer than today. And yet the Arctic ice cap didn’t disappear,” says Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, a professor at the Centre for Ice and Climate at Copenhagen University’s Niels Bohr Institute, who headed the project.

The Eemian was warmer than previously thought

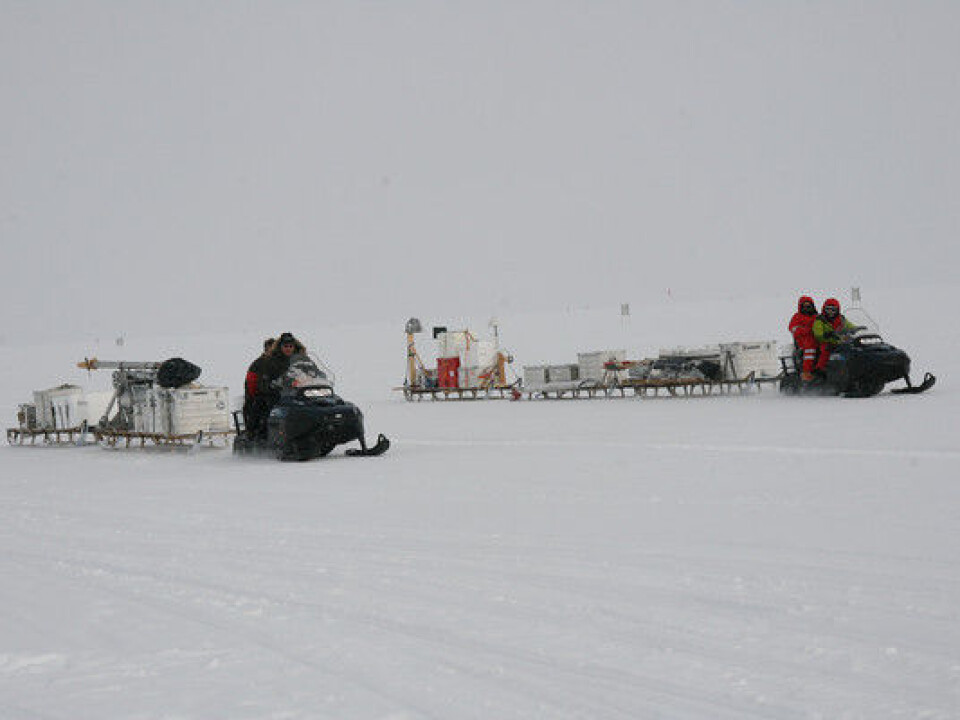

Drilling a 2.5-kilometre long ice core out of the Greenland ice sheet is not something that’s done in one afternoon. It’s a huge effort which takes many years to complete. For years, Jensen and her colleagues have travelled north to the icy island to complete their climate archive.

Back in Denmark, they then mapped the composition of the ice in their sophisticated labs.

The ice is formed by the snow that once fell over Greenland and which due to the cold has remained there ever since.

When, over the course of one year, the characteristics of the snow changed and fell in varying amounts, each year’s snowfall formed a distinctive layer, which together with all the other layers makes up a long timeline over the period, just like year rings on a tree.

The researchers put a particular focus on measuring the oxygen concentration in each individual layer. This provides them with highly specific information about how the Arctic looked back then. This data reveals how thin the air was in the atmospheric layers where the ice was created.

Temperature determined by oxygen isotope

Layers with high oxygen concentrations are formed on a thin ice sheet close to the surface of the sea. Layers with low oxygen concentrations, on the other hand, have probably been formed high up on the top of a thick ice sheet, where the air was thin.

By measuring how the oxygen concentration changed depending on the time, the researchers got a clear picture of how the ice sheet occasionally grew but mostly shrank during the Eemian period.

At the same time, they could measure specifically how warm the climate was at a given time in the period by determining the concentrations of the special oxygen isotope O18.

“The prevailing view has been that the average temperature back then was between three and five degrees warmer than today, but we can now demonstrate that this estimate was too modest,” says Jensen.

“We can now say that the climate during the Eemian period must have been warmer than previously thought, and that’s a great scientific discovery.”

A quarter of the ice sheet disappeared

The warm climate did indeed cause the ice sheet to melt on the surface and along the edges. And its thickness was reduced by a full 400 metres through the Eemian period as the melt water trickled out into the surrounding sea.

But the surprisingly warm climate only ate away a quarter of the ice sheet, so it survived. After millennia of melting, there was still plenty of ice left, even though the ice sheet was 150 metres thinner than it is today.

According to the researchers’ calculations, the melting of the Greenland ice sheet can only account for a rise in sea levels in the oceans of two metres.

But since it’s known that sea levels back then were 4-8 metres higher than today, there’s still 2-4 metres of sea-level rise to be accounted for. And that can only come from one source: the Antarctic ice sheet.

“The good news is that the Greenland ice sheet isn’t as sensitive to rising temperatures as we thought,” says Jensen.

“The bad news is that the heat must have resulted in a significantly greater melting of Antarctica than we thought. The contribution of the giant ice mass to global sea-level rise must have been quite substantial.”

The new study is published in the journal Nature.

-----------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther