Greenland’s cultural heritage threatened by climate change

Archaeologists estimate that Greenland has more than 6,000 sites with cultural monuments. Due to climate change, a significant part of these treasures may be under threat.

Man settles down where there are good chances of finding something to eat. In Greenland, this has mainly been in coastline locations, where fishing opportunities were good and plenty of seals were to be found.

For most of the year, Greenland’s coasts have been protected by sea- and drift ice, which function as nature’s own coast guard and breakwater. But there is less ice now and it’s there for shorter periods, while more and stronger storms increase the degradation of the cultural monuments.

Elsewhere, there is a risk of bones and wooden materials being eaten up by bacteria and fungi when the permafrost starts to thaw.

The consequences of erosion and thawing permafrost has prompted Greenland’s National Museum to team up with experts in the field to take a closer look at these challenges. The project is titled ‘Alle tiders mennesker’ (‘People from all ages’)

National Inuit treasures may vanish into the sea

Pauline Knudsen, curator at the Greenland National Museum, is concerned:

“Specialists who visited the archaeological site Dødemandsbugten (Dead Man’s Bay) in northeast Greenland five years ago said that ten metres of the coastline had been eaten up by the sea over the past 80 years. If this erosion continues, the relics of Inuit culture will be washed into the sea in the foreseeable future,” she says.

“Newer buildings, too, such as whaler cabins, have sunk into the sea because the coastline where they once stood had eroded away. Another threat from climate change is the thawing of permanently frozen dunghills. If these start to thaw, how quickly will it go? Are we talking five years or five hundred? Those kinds of concerns form the basis of our project.”

A cultural heritage of overwhelming proportions

In recent years, more attention has been given to the thought that some cultural monuments need to be preserved for posterity and for new research methods that will inevitably pop up.

We fear that the problem with the scrub will be moving north as the temperatures are rising. Here, it will destroy the fixed structures and will only leave traces of wood and bones. So it’s a bit of a race against time.

The new project is intended to provide an overview of what is at risk and how much should be documented before it disappears. It also seeks to determine which sites should be monitored and whether action needs to be taken to counteract the degradation of specific cultural treasures.

Knudsen and her colleagues are not planning to examine all 6,000 national treasures. That simply would not be possible. But in a pilot project started in Nuuk last summer, researchers tested some methods which should provide a few answers to how climate change affects the ancient monuments.

Along the way they encountered some surprising challenges.

An interdisciplinary approach

The pilot study is intended as a prelude to a more comprehensive research application.

PhD fellow Christian Koch Madsen tells us about the background of the fieldwork:

”I searched the archives and found some excavation reports in which permafrost with great conditions for preservation had been identified in the 1930s and the 1980s. That provided us with a basis for comparison. Back then, archaeologists didn’t cover up the holes from their excavations.”

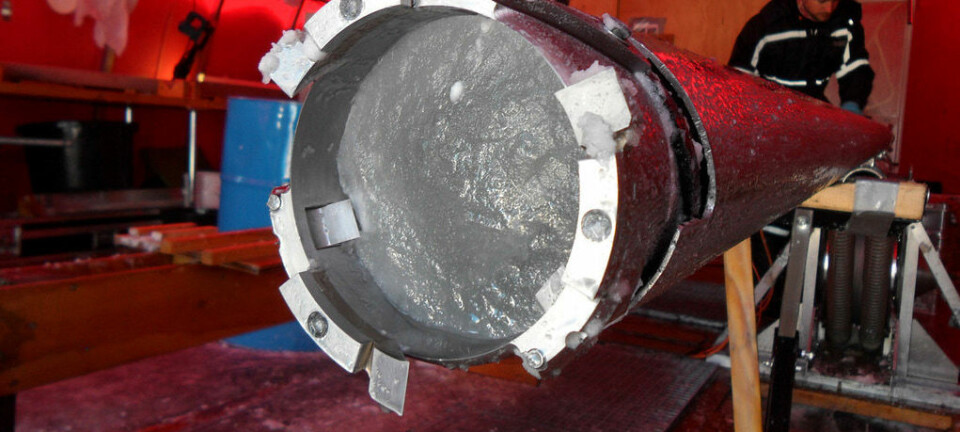

“We dug into the dunghills to check if there was still permafrost. At one site we made a small excavation to see what would happen if we dug a metre into the profile to extract some bone material for dating. At another site, we took samples for DNA analyses.”

The team consisted of several archaeologists, a geographer, a DNA researcher, a chemist and a pollen analyst.

This interdisciplinary approach has many advantages, says chemist Henning Matthesen, of the Department of Conservation at the National Museum of Denmark:

“When we’re sitting in the excavation, we as professionals notice certain things. It was for instance good to be told what archaeologists can read from a sectional view of a dunghill because we need to develop a common terminology and find a common ground.”

Decurrent water was a surprise

Sitting in a warm office imagining how things should be done out in the field is one thing. It’s a bit different when you’re standing knee-deep in mud and you suddenly realise that your conception doesn’t quite correspond with reality.

”We had thought a lot about sea level rise and coastal erosion being hard on the coastlines. At some sites, however, it turned out that the water from below wasn’t the big problem,” explains Matthiesen.

Rather, it is the water coming from behind that’s problem. When water runs down along the cliffs, it runs below the dunghills and washes them out. The dunghills then risk collapsing. That’s something we had not expected back in the office.”

But it wasn’t just the water that surprised the researchers:

Willow scrubs may contain a horror scenario

”On photographs from the 1980s, we see that the willow scrubs are merely small creeping shrubs. Today, the willow scrub is two metres tall and in some places it has a preference for ruins, where its roots can be quite destructive,” says Matthiesen.

”That’s another thing we hadn’t really considered. We had not imagined that we would be fighting our way through the thicket, which certainly wasn’t made easier with all the equipment we had to carry around. In addition to this being a practical problem, there’s also a horror scenario hidden in the willow scrub.”

Madsen explains:

”We fear that the problem with the scrub will be moving north as the temperatures are rising. Here, it will destroy the fixed structures and will only leave traces of wood and bones. So it’s a bit of a race against time.”

-------------------------------

(This article is reproduced on this site by kind permission of Polarfronten, a Danish online magazine with news about polar research.)

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther