No evidence that Danish bog bodies were gay

And it’s unlikely that they were mutilated and tortured before their death.

Danish bogs have preserved some unique archaeological finds: Grauballe Man and Tollund Man, to name a few.

One theory was that these Iron Age corpses were mutilated and tortured until they died. But what could explain this particularly violent death? Did something about them set them apart from the rest of society at that time? A punishment perhaps for carrying a disease, or even being gay?

While archaeologists can’t ask the bog bodies about their sexual orientation, they can at least say that none of them were physically distinct to other Iron Age remains, says Professor Niels Lynnerup from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. He is one of the anthropologists behind a new analysis of Danish bog bodies.

“Based on our studies we can now say that there is nothing about these people that would distinguish them from other Iron Age skeletons. They did not have conspicuous pathologies, they were not two metres tall nor particularly small, or anything else that could physically separate them from the crowd,” says Lynnerup.

Read More: New method reveals the secrets of bog bodies

Bog breaks down hard skin

It was previously suggested that the bog bodies could have been homosexual, because they seemingly had such delicate hands.

“People thought that they mustn’t have occupied themselves with hard, manual labour, and were therefore fine men. There was even a suggestion that they were gay,” says Lynnerup.

Of course you cannot identify someone’s sexuality from their physical exterior, but Lynnerup and his colleagues can at least put this line of reasoning to rest.

Today, scientists know that the outermost layer of skin that contains the protein keratin is dissolved in acidic environments, says Lynnerup. So, the hands lack the hardened, calloused look that they probably had.

The new analyses, including x-rays, CT-scans, and 3D reconstructions, were conducted as part of a collaboration between the Danish museums, where the bog bodies are on display. The new techniques are an improvement on previous analyses.

Read More: Denmark’s first Viking king printed in 3D

New information on the bog bodies emerges

The first Danish bog body was discovered in the 1800s.

Of the recent Danish discoveries, Tollund Man (400 to 300 BCE) and Grauballe Man (300 to 200 BCE) are the oldest. Both of them were discovered around 70 years ago and were first studied in 1950 and 1952.

Since then, they have yielded lots of information on how the fen affected their skeletons, says Lynnerup. Just as the bog can dissolve the outermost layers of skin, it can also decalcify the bones making them soft and flexible, almost like wet cardboard.

“The bones of a ‘fresh’ bog body are indeed very soft. If you didn’t know how they should be preserved, and we didn’t when some of the oldest bodies were discovered, then they would shrink and stiffen,” he says.

“When scientists studied the bodies later on, they didn’t think so much about the desiccation, - of which there really wasn't much documentation either. Instead they thought about which rare disease could have caused the bones to distort and shorten, and if these people suffered from such a rare disease, then that might explain why they were sacrificed. Today, we know that it’s really about what has happened in the bog,” he says.

Read More: Another female Bronze Age icon is now known to have travelled across Europe

Tried to ‘repair’ the bodies

When some of the first bodies were excavated it was custom to try and ‘repair’ them. For example, by stuffing their faces with various modern materials to prevent them from caving in.

This was the case for Auning Woman, who was discovered in 1886. In the absence of modern conservation methods they stuffed her warped skull and sewed her head back together.

The idea was to make it easier to see how she once looked when alive, but the results were often not good. In this case it made the Auning Woman’s head look like a football.

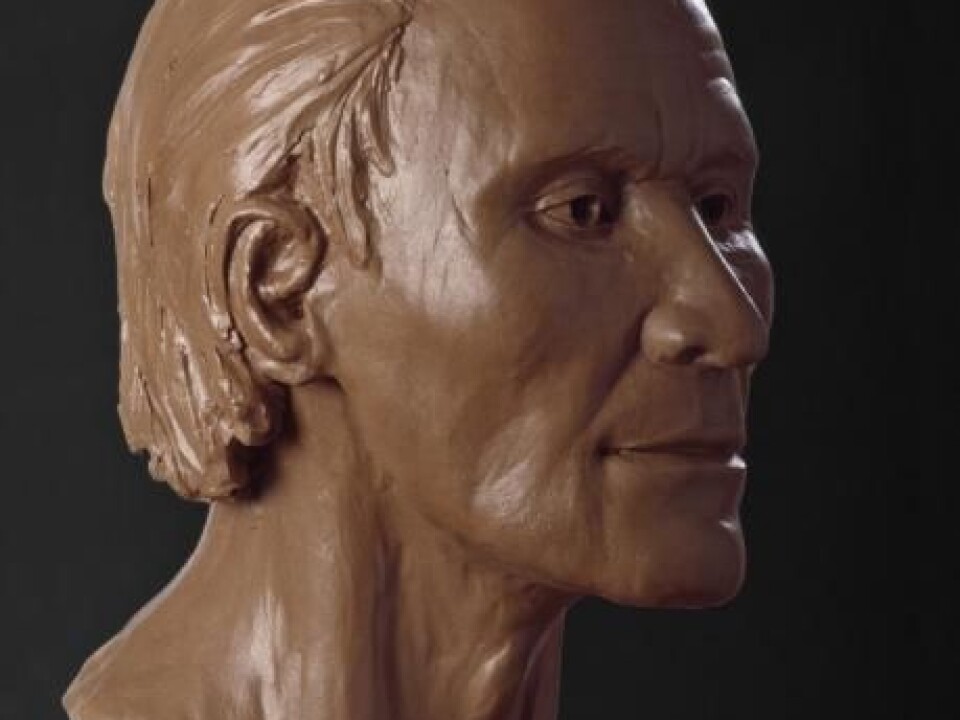

Today, archaeologists can recreate their faces by scanning them and making a 3D reconstruction.

This is what Lynnerup and colleagues have done with Grauballe Man, as shown above.

Read More: Archaeologists think they have found Copenhagen’s oldest church

Theory about Grauballe Man’s legs is wrong

The new investigations have also revealed other remarkable discoveries about the bog bodies that we still know so little about. For example, there is no evidence that they were tortured before they died as is commonly thought.

Multiple sources suggest that Grauballe Man took a blow to the head and had his legs broken by his executioner or executioners.

“When he was first found, the x-ray analyses were not as good as they are today. You could see there was a break, but you couldn’t analyse it more closely and you couldn’t see if it happened when he was alive. Then the theory was launched that he was perhaps hit on the head and his bones were broken so he couldn’t run away, and this has hung around,” says Lynnerup.

Another theory suggested that they were killed with more force than was necessary as part of a ritualistic killing.

Read More: Archaeologists excavate 400 Iron Age houses in Denmark

Post mortem injuries occured in the bog

Scientists already knew how Grauballe Man died: A single sharp cut to the throat from ear to ear while he knelt with his head pulled back. But the new analyses reveal that the damage to his head and legs probably occurred post mortem.

New scans also revealed that the damage to his head and legs probably occurred due to the massive weight of the bog pressing down on the soft bones.

The same also applies to another famous bog body, Borremose Woman, who was discovered by peat diggers in North Jutland in 1948. Original analyses suggested that she must have received a violent blow, which crushed her face.

“In the case of Grauballe Man and Borremose Woman, we can see that they have been damaged after they died. It may not be the case for other bog bodies, but for these two, we’re not talking about an extremely violent death,” says Lynnerup.

Read More: Archaeologist: Excavate more before climate change destroys our cultural heritage

“They weren't meant to suffer”

These new conclusions fit with similar work by the Irish archaeologist Eamonn Kelly from the National Museum of Ireland as part of the Bog Bodies Research Project. He has studied all of Ireland’s bog bodies using CT and MRI scans, palaeodiet analyses, microscopy, and studies of the bodies’ cells and tissue to identify any diseases.

The Irish bog bodies are relatively new discoveries—all were excavated since 2003 and Kelly has found no evidence that they were tortured.

“There's been discussions as to whether the bog bodies were tortured before their death, but we found no proof of that in our investigations,” says Kelly.

Interestingly, the Irish bodies actually have more injuries, but it was the first injury that killed them or made them unconscious.

“They weren't meant to suffer. There was no wish to be cruel to these people. The subsequent injuries seem to be made with ritual purposes,” he says.

Read More: Burnt down Iron Age house discovered in Denmark

A local or an outsider?

So if they weren’t tortured to death, what did happen to them? Who were these people and why were they killed and buried in a fen?

These answers could be just around the corner. Lynnerup and colleagues are currently awaiting the results of strontium isotope analyses, which should indicate whether the bodies were local or had travelled great distances to the site.

A local signature could indicate that they had committed a crime and were sacrificed as a result. But being chosen as the fen’s victim may also have been an honour, for the victim and their family, says Lynnerup.

Alternatively, if the strontium analyses indicate that the bog bodies had travelled to reach the fen this could suggest that they were high status individuals or even royalty.

One day, Lynnerup hopes to use DNA analyses to answer such questions: Were any of them related? Were they a part of a wave of immigration? Were they already ill when they died?

“Ten years ago, DNA techniques required relatively large, intact pieces of DNA. But this is reducing all the time, and completely new techniques are emerging. If one day we could use DNA, it would probably give us lots of answers,” says Lynnerup.

----------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article at Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex