New method reveals the secrets of bog bodies

Protein analyses on Denmark’s large collection of bog bodies gives archaeologists deeper insights into Iron Age culture and society.

Archaeologists have learned a lot about the lives of Iron Age Europeans from the mummified remains preserved in bogs--including how they dressed.

But not even the best-preserved bog can withstand the ravages of time. And archaeologists could not identify the exact origin of fibres from hair, wool, or skin in such old, degraded garments.

But this is all about to change, thanks to a new method, which analyses proteins in the fibres to determine exactly what type of animal they came from.

“With proteins, we could make a completely accurate species identification in 11 out of 12 samples and show that species identification that was carried out by microscopy on half of the samples was incorrect,” says lead-author Luise Brandt, who completed the research during her Ph.D. at the University of Copenhagen, but is now based at the University of Aarhus, Denmark.

The new technique can for the first time help archaeologists to differentiate between goats or sheeps wool, for example, which would otherwise be difficult to do when studying hairs that had spent 2000 years in a bog, says Brandt.

Skins provides insight into Iron Age culture

Karin Frei, from the National Museum, Denmark, sees great potential in the new method, which should help archaeologists to learn more about how the prehistoric societies produced clothing from animals.

Frei was not involved in the new research, but she has also studied wool garments preserved in peat bogs.

“The method is very exciting because it allows us to clarify several archaeological issues, which have often been difficult to study with any certainty. This new method allows us to form a much more accurate picture,” says Frei.

According to Brandt, her method should help to identify how people selected the material from which to make their clothes, which may give an insight into the resources available at the time in that society.

"It’s important to know what kind of material you have chosen for what [purpose], and there were various skins that were particularly useful for different functions. It tells us whether they kept or hunted the animals at that time, and beyond the practical aspects, the choice of material also reflects their tastes, or a desire to send a certain signal through what they wore,” says Brandt.

For example, clothes are typically an indicator of a person’s position in society.

Read More: Fashionable Vikings loved colours, fur, and silk

Hair breaks down in acidic bog environment

Even 2,000 years ago, Iron Age people in Northern Europe cared about what their clothes were made of and how they were made.

Archaeological findings have revealed, that people had a deep knowledge of the different animal skins and their characteristics, which influenced the cuts and appearance of the materials they used.

But there was a lot of confusion about which type of animal skins were actually used.

In 2011, Brandt tried to extract DNA from various materials found on bog bodies in Denmark. But she hit a dead end.

The DNA was too degraded to work out what type of material the clothes were made out of. So she switched her attention to proteins.

“I found out that proteins are preserved, ten times longer than DNA,” says Brandt.

The protein analyses showed that the composition of amino acids--the building blocks of proteins--in the various material changes according to animal species. They can therefore act as a fingerprint for the type of animal that the material came from.

Cloaks sewn with great care

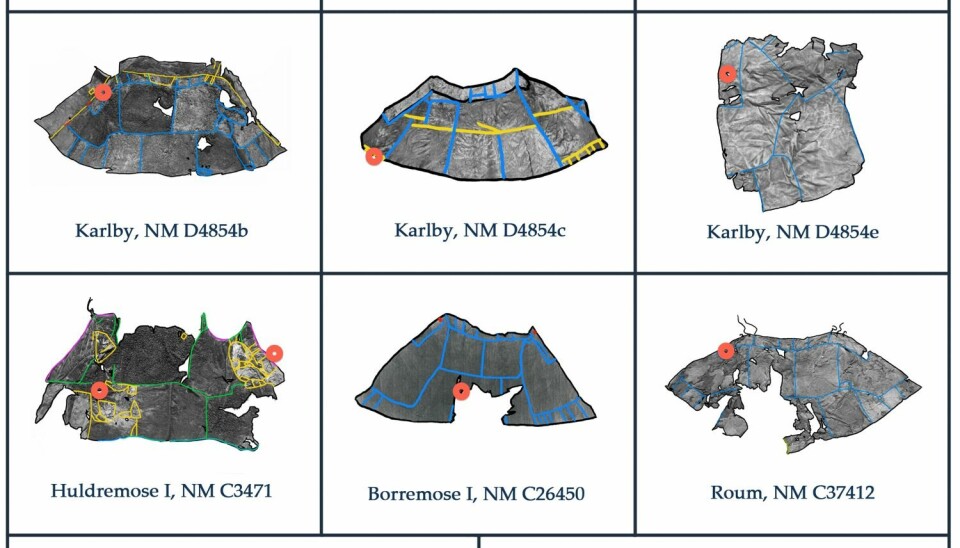

Brandt analysed 12 samples from ten cloaks and a tunic from the Danish National Museum’s collection of leather suits that were preserved at a number of archaeological sites in Jutland, West Denmark. All of the garments are around 2000 years old.

She successfully identified the animal species in 11 out of 12 samples. Two samples came from cattle, three from goat, and six from sheep. The twelfth sample is from either a sheep or a goat, but this test was inconclusive as the protein that distinguishes between sheep and goat was not preserved.

The results suggest that Iron Age garments were made exclusively from the skins of domesticated animals, and not wild animals as popular mythology often suggests.

Read More: Unique jewellery from the British Isles found in Danish Viking grave

Tunic made from a young calf

More sensational is the discovery that that one of the garments, a tunic buried in Møgel bog in Jutland, west Denmark, was made from calf leather. It contained a protein found in blood—haemoglobin.

This particular type of haemoglobin is only produced during the last months of pregnancy and in the first three months after birth in the young calves, after which it is replaced by another type of haemoglobin.

“This extraordinary result told us that it was not only made from leather from a cow, but on top of that, it came from a calf,” says Brandt.

This discovery, along with the ability to extract proteins from 2000 year-old animal skin, gives archaeologists a greater understanding of Iron Age textile production.

Read More: Arctic tomb preserves oldest known Inuit dress

Perhaps leather was just as important as meat

Brandt speculates that the skins may even have been just as important as the meat to local Iron Age people of the time.

“I think that the smoking gun was the haemoglobin. We can see that they went to great lengths to make the garments and choose the right skin,” says Brandt.

“But now we can see that they used calfskin for the tunic, which could suggest that the skin was a really important part of why they slaughtered young animals and that it was an important product,” says Bradt.

Livestock in the Iron Age were well-developed, but our perception is usually that they were bred primarily for food. But the new results suggest that the animals served a larger purpose.

Frei agees.

“This is very important for how we view these Iron Age people and the society that they lived in,” says Frei.

“Because they chose calfskin, which is softer and more flexible than skin from older animals, we immediately get the feeling that these people didn’t just wear anything. It suggests a society that made clear decisions about what they found to be comfortable to wear, which is also what we do today,” she says.

----------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Scientific links

- 'Species Identification of Archaeological Skin Objects from Danish Bogs: Comparison between Mass Spectrometry-Based Peptide Sequencing and Microscopy-Based Methods', PLOS (2014), DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0106875

- 'Burials in bogs – Bronze and Early Iron Age Bog Bodies from Denmark', Acta Archaeologica (2010)