1,000-year-old Viking toilet uncovered in Denmark

A deep hole containing human faeces has been discovered at a Viking settlement in Denmark. Is this Denmark’s oldest toilet?

In a Viking settlement on Stevns in Denmark, archaeologists have excavated a two metre deep hole. But it is not just any old hole. This hole, it seems, may be the oldest toilet in Denmark.

Radiocarbon dating of the faeces layer dates back to the Viking Age, making it quite possibly the oldest toilet in Denmark.

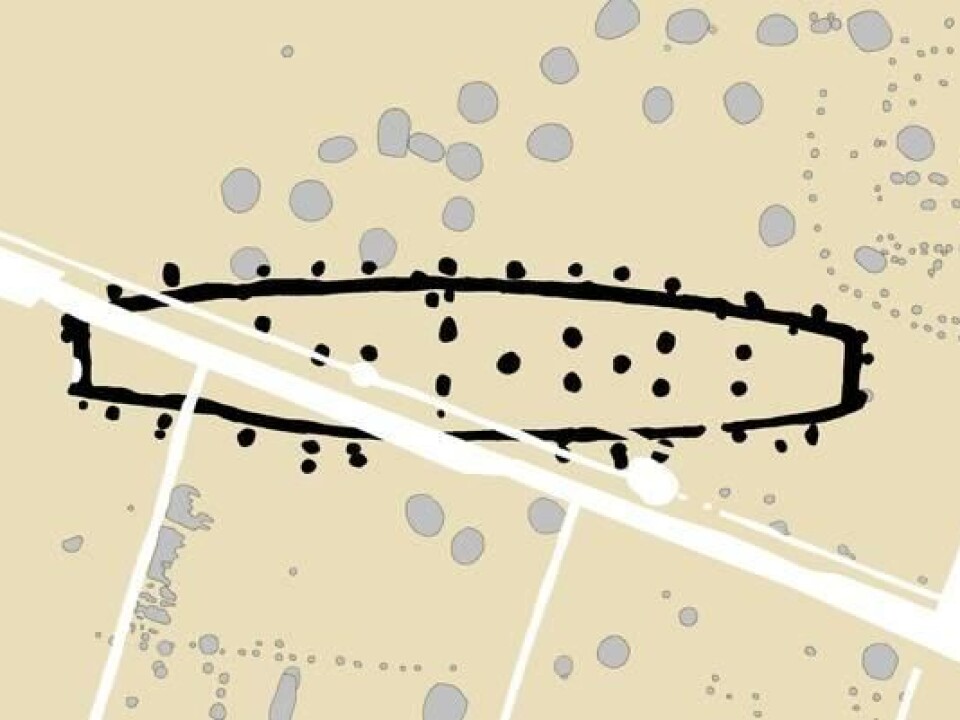

“It was a totally random find. We were looking for pit houses—semi-subterrenean workshop huts—and it really looked like that from the surface. But we soon realised that it was something totally different,” says PhD student Anna Beck from the Museum Southeast Denmark.

Apart from representing Denmark’s oldest toilet, the discovery goes against archaeologists’ theories surrounding people’s toilet habits through time, says Beck. Not least because it was discovered in an area of Viking countryside and not in a Viking city.

“We know about privy buildings inside cities in the latter part of the Viking Age and the early Middle Ages, but not from agraian settlements and farms. We imagined that people had defecated in the midden or in the barn with the animals in order to use their waste as fertiliser for the fields,” she says.

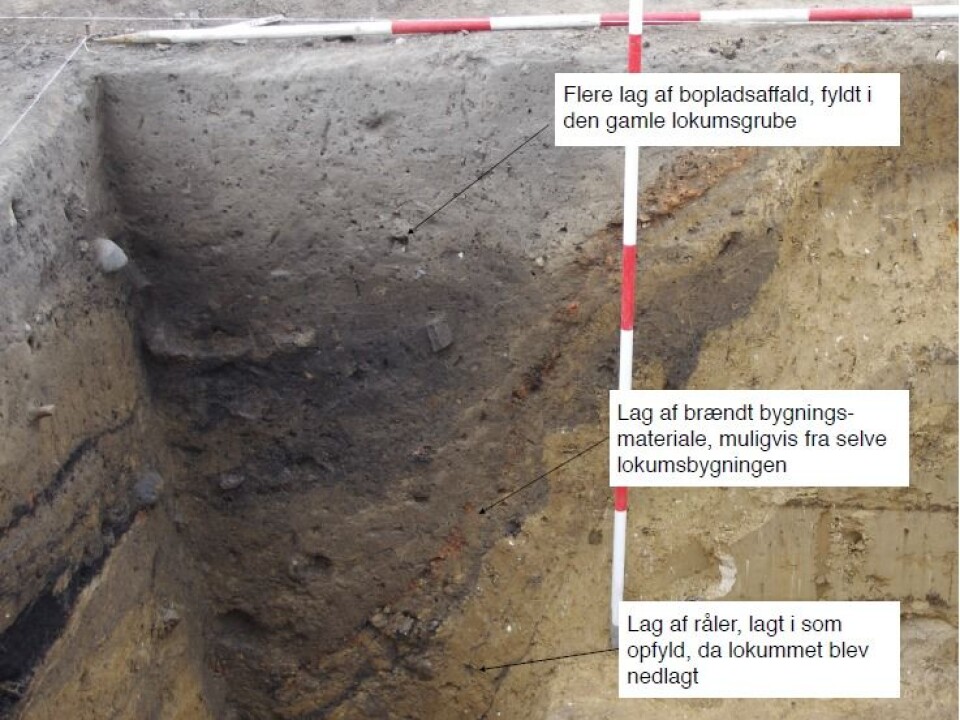

Macrofossil and pollen analyses revealed that there were mineralised seeds in the bottom layer—a process that takes place in low oxygen conditions with a high content of phosphate. The archaeobotanists also discovered a high concentration of fly pupae in the same layer.

Both results clearly suggest that the bottom of the hole were covered in a layer of—yes, that’s right, poo.

“Perhaps we’ve overlooked earlier faeces”

In the Viking towns, lots of people meant lots of human waste gathered together in one place, and so they needed a system to deal with it. In contrast, human waste in the countryside could be used as fertiliser, and was in principle a resource that could be collected and used.

This previously explained why archaeologists usually find do not such old toilets in what could be described as the Vikign countryside.

One of the exciting questions now is if toilets were actually a common phenomenon that archaeologists have just overlooked in the belief that they did not exist, says Beck.

“We could well have registered thousands of these pits and not thought that [they contained] faeces. It just looks like a dark layer. When you excavate in the towns you’re rarely in doubt—it often still smells of faeces. But there isn’t the same organic layer out in the field as there are in the towns, so here it decomposes by a completely different process of decay,” she says.

Honey or mead preserved in faeces

Scientific analyses of the sediments accumulated in the two metre deep hole confirmed that they were indeed human faeces.

Pollen analyses revealed a high concentration of insect-pollinated plants—flowers. Flower pollen is found in particular in honey, which is typically a part of the human diet, says Beck.

“I don’t know whether Vikings sat and ate honey, or if it was mead, but the interpretation at least is that it’s pollen from honey, and that is rarely used for feeding animals.”

Pollen analyses also showed that there was not much airborne pollen in the soil layers, which indicates that the hole had been covered, perhaps inside a small building.

When the results of the pollen analyses came back, Beck went back to the archaeological material to see if she had overlooked anything. She discovered two post holes, one on either side of the pit, which could easily pass for a closed construction, she says.

“It shows that there could’ve been a small house built around it, which could explain the lack of airborne pollen. In the space itself there’s residues of building materials that could originate from the building when it was demolished,” she says.

Study turns a blind eye to written sources

Toilets are mentioned in a number of the Icelandic sagas where they are described as separate buildings from the farmstead. But Beck has chosen to not draw too heavily on these written historical sources. In her own words she has chosen to turn a blind eye “a little on purpose” in favour of taking the archaeological discovery as the starting point for her interpretations.

“Written sources such as the Icelandic sagas have always been considered “closer” to people—who they were and what they thought—than the material sources. Therefore archaeological finds are often used to illustrate the story. But sometimes you risk mistreating the archaeological discoveries, because you don’t handle them on their own terms,” she says. “Particularly if the written sources orginates from later periods which might describe completely different conditions.”

“I’m trying to turn things around and say that the material sources perhaps contain a part of our history, which serves as more than an illustration. The material evidence poses new questions and if we don’t take them up, then they’ll never be answered,” says Beck. “In this case, the material and written sources play well together, but sometimes they do not, and what is then the ‘right’ story? My claim would be that they both are - even if contrary.”

Colleague: “Toilets are a new concept”

But you cannot just ignore the written sources, says Kjartan Langsted, director of Museum Nordsjælland in Denmark. He did not partake in the new excavation but is familiar with the findings.

He suggests that ethnology—the study of people’s culture and daily lives in the past—does not point towards a toilet as the explanation.

“My main counter argument is that toilets [in the countryside] are a relatively new concept until recent times. Ethnographic sources show that the first toilets were introduced in the countryside in the middle of the 1800s. Before that it was normal to take care of business on a midden or in the stable,” says Langsted.

“Today a trip to the toilet is private, but that doesn’t mean that it was this way in the past. Everything was a resource to be used,” he says.

Langsted does not entirely rule out that the toilet could have been introduced in the Viking age—but he is waiting to see evidence from a more aristocratic environment than the excavation site at Strøby Toftegaard. The site may well have been a society of high status, but not on the same level as other Viking sites in Denmark.

“From what I can see in recent sources, it’s strange that it was introduced at this location and at this time. But that doesn’t mean that I reject the idea. There are also good arguments towards the toilet interpretation, for example, the scientific analyses that show that it is excrement,” he says.

“But” he adds, “you should also consider that the [excrement] could have reached the hole by some other means.”

Humans separated themselves from their animals

Beck has met resistance from academic circles over her interpretation of the pit as an early toilet prototype.

“Which is interesting, because I think that it’s hard to reject,” she says.

The idea that excrement was used as a resource on fields, requires people to have a modern, rational relationship to life,” says Beck.

“But we know from cultures the world over that the treatment of faeces is surrounded by complicated cultural and social rules and taboos. From toilet culture, you can learn a lot about the norms and rules of that particular society,” she says.

“For example, we know that animals, which had previously lived under the same roof as humans for thousands of years, were moved out of people’s homes at this time. The distance between humans and animals became larger, both physically and mentally. That ideal doesn’t fit so well perhaps with them sitting out in the stable to defecate along with the animals,” she says.

---------------

Read more in the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex