Scientists discover gene to prevent blindness in diabetics

Diabetics who carry a specific genetic variant may be protected from a severe eye disease, which can lead to blindness if untreated.

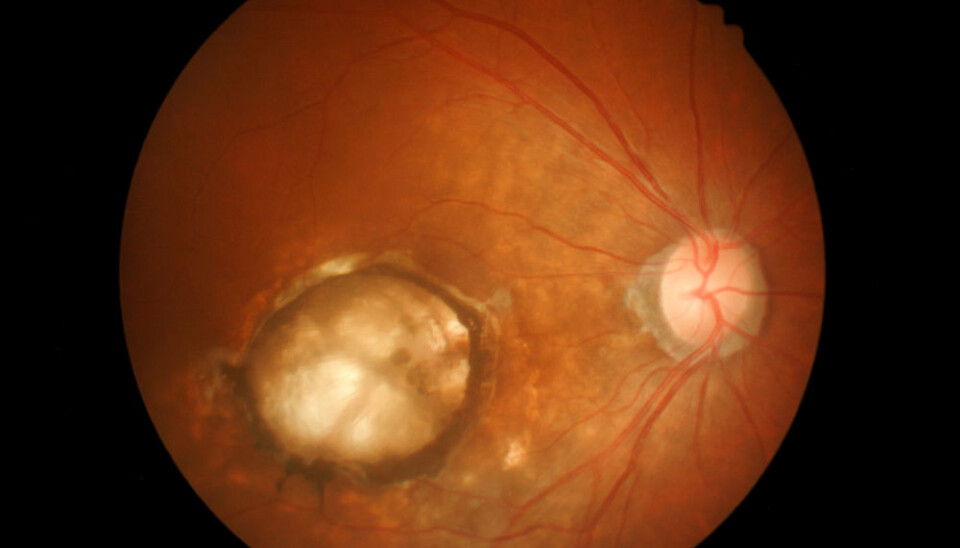

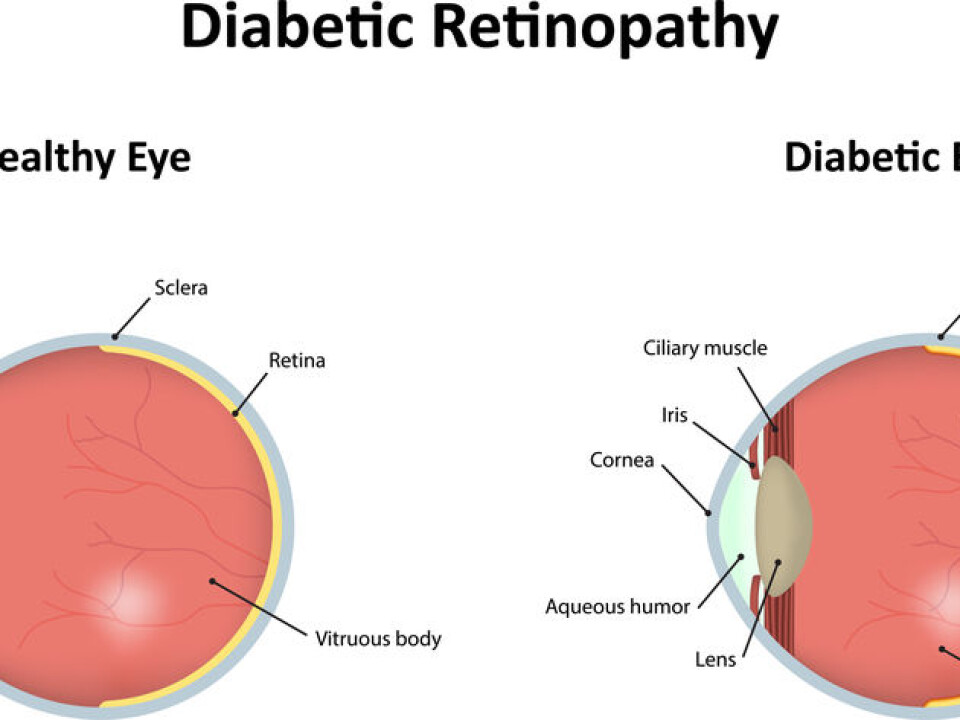

Scientists have found a special gene variation that protects diabetics against the eye disease retinopathy, which makes the small blood vessels in the eye begin to grow and spread and eventually leads to impaired vision and blindness.

More than 90 per cent of patients who have suffered from diabetes for at least 20 years will contract the disease.

Clinical Professor Henrik Bindesbøl Mortensen from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, is one of the scientists behind the new study. He calls it the first step towards understanding the disease and to develop better treatments.

"In the long run, a better understanding of the disease at the molecular level will lead to the development of new drugs to stop the disease by targeting specific proteins in the eye," he says.

The study is published in the scientific journal Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology.

The gene that controls cell death

The scientists monitored the progress of 130 people with type-1 diabetes for 16 years. Patients had their eyes photographed in 1995 and again in 2011 to see if diabetes had affected their eyes and vision.

At the same time, they studied the patients’ DNA. The scientists looked at 23 genes that have previously been shown to influence the development of the disease.

They discovered that none of the patients who carried a specific gene variation in the so-called CTSH gene showed symptoms of the devastating eye disease.

Research assistant and medical student Kristian Sandahl from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, is the lead author on the new study.

According to him, the CTSH gene carries the recipe for a protein, which controls the cell death and the formation of blood vessels.

"The gene controls the actual cell death in the beta cells, which are the ones that make insulin in the pancreas. It also makes new blood vessels,” says Sandahl.

“It's the first time that this gene has been associated with this sickness. You can imagine that it's functional in the eye--either it has something to do with the control of cell death in the eye or blood vessel regulation," he says.

In Denmark there are 30,000 people currently living with type-1 diabetes. Half of them have retinopathy, and 20 per cent will develop the disease.

Mutation aggravates diabetes disease

Previous studies have shown that this particular variant of the gene exacerbates diabetes.

All genes occur in pairs called alleles. One allele comes from the mother’s side of the family, and the other from the father’s side. The alleles in the CTSH gene can occur in three variations: CC, CT, and TT.

Patients with the TT combination seemed to be protected from blindness.

"We were actually surprised when we found that carriers of the T-allele were protected against the development of the dreaded eye disease,” says Mortensen.

“In contrast to previous studies of the pancreas where T-allele makes the disease worse, here we found that it was associated with less severe changes in the retina of the eye," he says.

Small but interesting study

Allan Vaag, a clinical professor at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, studies diabetes and genetics. He thinks the results are interesting.

"It's exciting, and I think it should be followed by other studies. Perhaps we should pay special attention to patients who have this gene variant and a higher risk of developing blindness. Such a finding may be of great clinical importance," he says.

At the same time, he emphasises that the study is too small to make definitive conclusions.

According to Vaag, the statistics are not yet strong enough as it is a small study, and so the result may yet be a coincidence. He will not be changing his treatment plans just yet.

The lead scientist Kristian Sandahl is aware of this, but he believes nonetheless that the statistics are strong.

"It's one of the largest studies ever made of this nature and it's the first time the gene is linked to this specific eye disease,” says Sandahl.

“We have corrected our data for multiple additional factors, so we feel that our statistics are quite strong," he says.

He agrees however that the results need to be validated in a future study.

--------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex