Diabetes gene found on Greenland

Scientists find genetic variant among Greenlanders that greatly increases the risk of developing diabetes.

Scientists have discovered a genetic variant that dramatically increases the risk of type 2 diabetes among Greenlanders.

The variant is found in close to one in five people in the Greenlandic population and entails an 80 percent risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

The connection between a genetic variant and type 2 diabetes is the clearest tie that has ever been found.

“It’s extremely interesting. The connection is much stronger than anything that has ever been reported before.”

“The discovery gives us a new understanding of the direct sequence of causes from the genetic variant to the development of type 2 diabetes. We can use that knowledge to better understand the illness -- outside of Greenland as well,” says one of the scientists behind the study, Professor Torben Hansen of the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen.

The study was recently published in Nature.

Critical colleague enthusiastic about the new study

Dean Allan Flyvbjerg of the Faculty of Health Sciences at Aarhus University has conducted research on diabetes, but has not participated in the study. In fact, he is not normally a proponent of genetic studies of type 2 diabetes.

But this study caught Flyvbjerg’s attention.

“I’ve not previously believed one bit in genetic testing for type 2 diabetes. However, this study has made me reconsider. When such a clear signal is found in genetic tests, it becomes possible to use it clinically to screen for risk of type 2 diabetes. It then becomes much more interesting.”

“However, screening should only be carried out if there is something to offer the patients afterwards. If not, knowing whether there’s a risk would be worthless,” Flyvbjerg points out.

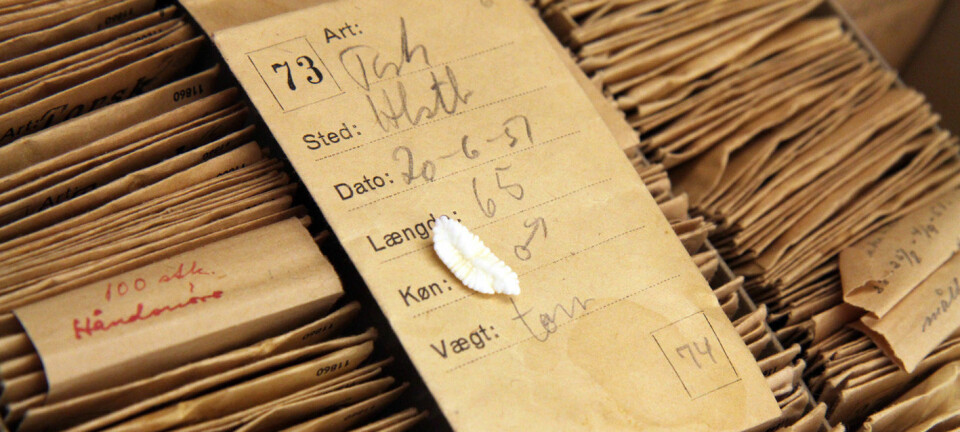

A quarter of a million genetic variants examined

The scientists checked 5,000 Greenlanders for the presence of 250,000 genetic variants with an influence on the carbohydrate metabolism, among other things.

The genetic variants were then weighed against the blood tests of the individual Greenlander’s ability to remove sugar from the blood after drinking sugar water -- a standard way of testing for diabetes and preliminary stages to diabetes.

This allowed the scientists to see whether the blood sugar problem is connected to specific genetic variants.

The study showed that people with a certain genetic variant had a markedly higher risk of having type 2 diabetes or preliminary stages to type 2 diabetes. They were unable to remove sugar from the blood as efficiently as people without the genetic variant.

The scientists found the genetic variant in 17 percent of the Greenlandic population, while 3-4 percent had two copies of the variant.

Among the people with two copies of the variant, 60 percent of the 40-60 year olds had developed diabetes.

The connection hasn’t been more evident anywhere else in the world,” says Hansen.

Genetic variant leads to missing protein

However, the genetic variant that was studied is not isolated to the Greenlandic population. It’s also found among Europeans, where it doesn’t cause diabetes.

Because of this, the scientists concluded that the genetic variant itself is not the cause. Another genetic factor, which in Greenlanders is passed on through this genetic variant, had to be the cause.

In their further studies, the scientists found a new and hitherto unforeseen genetic variant that is only found in Greenlanders, but is inherited with the other genetic variant that is found among people in the rest of the world.

The recently discovered variant is a genetic mutation that entails a so-called stop codon that causes a given protein not to be produced.

If a person carries a single copy of the variant, just half the amount protein is produced, while two copies stop the production of the protein entirely.

“We were extremely lucky to find the genetic variant. It means that we can map the entire cause of the development of type 2 diabetes from genetic variant to insufficient removal of sugar from the blood,” says Hansen.

Muscles don’t absorb sugar correctly

The protein in question plays an important part in the development of diabetes among many Greenlanders.

The protein is located in the muscles and ensures that sugar transporters are moved to the surface of the muscle when there’s sugar in the blood.

If the proteins are missing, the sugar transporters are not moved to the surface of the muscles, and that means that the muscles fail to absorb the sugar. Inability to remove sugar from the blood is one of the signs of diabetes.

But why do 17 percent of the Greenlanders have a genetic variant that gives them an enormous risk of developing diabetes?

The scientists have a possible explanation for this:

“We speculate that it could have been an advantage for them in the past. Traditionally, Greenlanders lived almost solely on meat and fat from fish and mammals. They ate very few carbohydrates. That’s why it could have been an evolutionary advantage for them to keep the sugar in the blood for a little longer when it was there,” says Hansen.

Could be the basis for new diabetes treatment

The new discovery gives new insight into diabetes -- not just in Greenland, but also all over the rest of the world.

The discovery not only tells the researchers that a genetic variant increases the risk of diabetes, it also tells them how it does this.

This can help build a foundation on which to base new types of treatment.

“For the first time ever, we have the entire connection between genetic variants and diabetes in people, not just in an animal model. When we carry out further studies of Greenlanders in future, we may be able to find out if we could make a medicine that could move the sugar transporters, or if we could make something other than insulin remove the sugar from the blood,” says Hansen.

Shows that small genetic studies could be better than large-scale studies

Flyvbjerg agrees that the Danish scientists have hit the nail on the head in their study.

He is particularly pleased that the researchers decided to carry out a study on a few thousand individuals from a specific section of the population, rather than carry out a study across many different groups.

“The study shows that it’s probably better to carry out small studies of specific sections of the population in order to screen for variants that increase the risk of different diseases.”

“The large genetic studies of large sections of the population don’t catch genetic variants that are specific to specific sections of the population. However, small studies do, and that’s why it would be much more interesting to continue in that direction in future,” says Flyvbjerg.

----------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Iben Gøtzsche Thiele