Did a recently found bird spear belong to a kidnapped Greenlander?

A recent archaeological find in Copenhagen – a bird spear from the Thule culture – has put focus on expeditions to rediscover Greenland 400 years ago and the expeditions’ kidnapping of Greenlanders.

The ongoing excavations for a new metro line in Copenhagen are revealing new knowledge about the fortifications of the Danish capital.

These excavations, which will last for several years, are also telling us about other aspects of life in the city, as the moats that formed part of the fortifications were filled with all forms of rubbish that was at hand when they were taken out of use.

Useful items also ended up in the moats from time to time.

One of the more unusual finds is part of a bird spear from Greenland, which was found in Kongens Nytorv, a major square in Copenhagen.

Common Greenland hunting tool

The bird spear was a common hunting tool in Greenland from around 1500 to some time in the 1900s.

Apart from the spearhead itself, the bird spear typically had three or four side prongs fixed to the middle section of the shaft.

These increased the hunter’s chances of success when he launched the spear into a flock of birds, and it is one of these side prongs that came to light during the excavations in the Copenhagen underground.

It was found in a moat that was once part of the fortifications around Copenhagen built by King Christian IV.

In the same layer of soil there were pieces of ceramics and tiles from the first half of the 17th century. The bird spear prong thus likely dates from the same period.

Thule culture find in Denmark a result of kidnapping

This is quite likely the first time that an item from the Thule culture in Greenland has been found in an excavation in Denmark.

That a hunting spear like this turns up in Copenhagen, thousands of kilometres from its origin, is probably due to kidnapping.

Following Columbus’ discovery of America, it was commonplace for Europeans who colonised tracts of land on the American continents to kidnap ‘savages’ and take them home to show to the monarch and the people – thus demonstrating the strength and sovereignty of the colonial power.

Columbus, for example, brought home a group of Arawak Indians following his first expedition, and Amerigo Vespucci brought home over 200 people from the New World in the years around 1500.

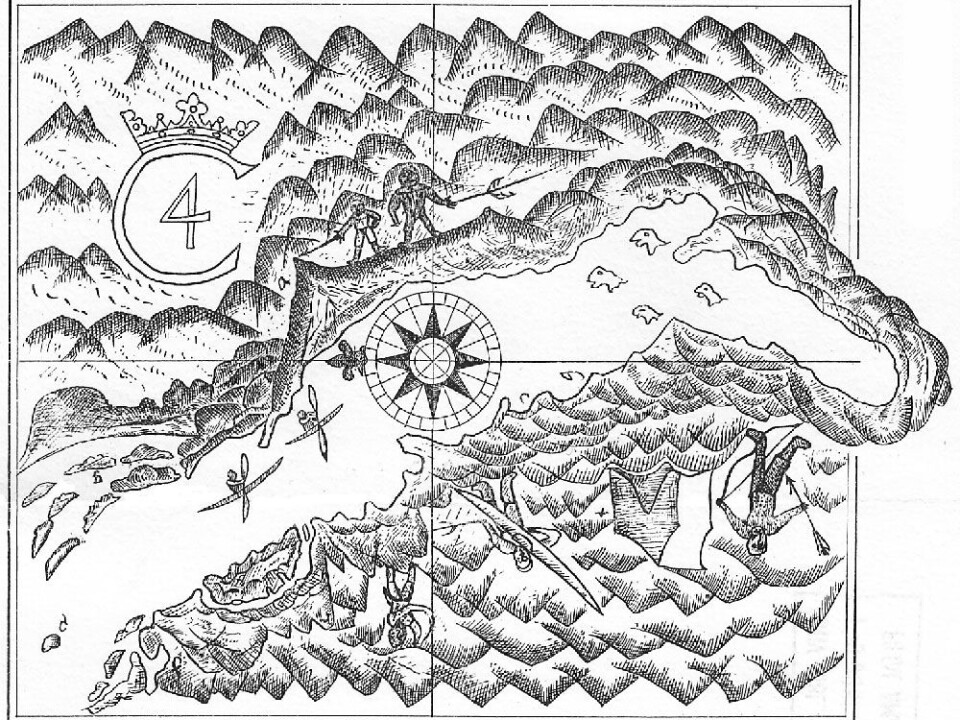

When, 100 years later, Christian IV took the initiative to rediscover the Greenland of the sagas, people only had a vague idea of the cold country in the North Atlantic Ocean.

The first expedition – commanded by the Scot John Cunningham and with the Englishman James Hall as the pilot – set off in 1605. The Dane Godske Lindenov captained the Røde Løve (Red Lion), which was one of the expedition’s three ships.

The participants reached such a great degree of disagreement during the voyage that Lindenov’s ship left the rest of the expedition off Greenland’s south-western coast.

The Røde Løve soon cast anchor in a fjord in south-western Greenland – probably Qeqertarsuatsiaat Kangerlluat.

Traded with Greenlanders, then kidnapped them

The mariners met Greenlanders and started trading with them. Shortly before setting sail for Denmark, Lindenov’s crew kidnapped two Greenlanders, probably both men, as living proof that Greenland had been rediscovered.

The Greenlanders fought back, one receiving wounds, and both were then tied up.

The Røde Løve’s arrival in Copenhagen on 28 July 1605 was the centre of much attention. People gathered on the quay and King Christian IV and Queen Anna Cathrine visited the ship to see the two Greenlanders, who later demonstrated their kayaks in Copenhagen’s harbour.

At some point the two Greenlanders were separated, and one was sent to Arild Huitfeld, one of the king’s Lord Lieutenants, at Dragsholm castle to learn Danish. We know nothing more about these two Greenlanders.

Two weeks after the Røde Løve’s arrival, on 10 August 1605, the rest of the expedition arrived in Copenhagen.

The last two ships had been further north, to the Itivdleq Fjord south of Sisimiut.

They had also met Greenlanders, with whom they exchanged nails and old iron for clothing, tools, sealskins and narwhal tusks. They kidnapped four Greenlanders just before they returned home.

Strong, homesick Greenlanders

On board the ship, the Greenlanders fought back, and the captain shot one of them. The dead body was thrown overboard, and the remaining Greenlanders were either tied up or locked up.

The three survivors are called Orm, Oye and Judecha in contemporary texts, which would be Umik, Oqaq and Kigutikkaaq today.

According to Jens Bielke, the secretary of Danske Kancelli (the Danish Chancery, the only government office for the Kingdom of Denmark until the Constitution of 1849), the Greenlanders were extremely strong, and he described how the Greenlanders could row as fast in their kayaks as ten of the king’s boatmen.

Although the Greenlanders were described as cheerful, they suffered greatly from homesickness and at one point they tried to escape in an umiak, also known as a women’s boat, which they had built during their stay in Denmark.

However, bad weather forced them to give up their escape attempt and they landed in the southern Swedish region of Skåne (Scania), where they stayed with local farmers until they were brought back to Copenhagen.

New expedition in 1606 met hostile Greenlanders

The following year Christian IV allowed five ships to be prepared for a new expedition. This time Lindenov was given overall command and Hall was once again the pilot.

The expedition set sail at the end of May 1606, with Umik, Oqaq and Kigutikkaaq as crew members. It was intended that these three would ease contact with the people the mariners expected to meet in Greenland.

According to Hall’s records, however, Oqaq and Umik died en route, while Kigutikkaaq’s fate is unknown.

When the ships reached Greenland in the vicinity of Sisimiut in August that year, they met Greenlanders as expected.

They traded this time as well, but the Greenlanders were described as more hostile than during the last expedition, and the trade did not give much.

The Greenlanders’ hostility may have been due to their knowledge of the kidnappings the year before, and this stay also ended with the expedition kidnapping five Greenlanders.

According to Claus Christoffersen Lyschander, later appointed as the Royal Historiographer, one of the Greenlanders jumped over board on the way back to Denmark.

The ships arrived in Copenhagen in the autumn of 1606 with the four surviving Greenlanders. Shortly afterwards, two of them tried to escape by kayak; one was caught and returned to Copenhagen, while the other escaped.

The others lived in Denmark up to 12 years after the kidnapping, but Adam Olearius, the German geographer and mathematician, reported that they were very sorrowful and one by one they grieved themselves to death.

Copenhagen ship-owners given whaling charter

Our knowledge of the third kidnapping is limited. The background for it was a Royal charter issued in 1636 to Copenhagen ship-owners allowing them to form a Greenland company for whaling and other similar purposes.

he charter called for the kidnapping of Greenlanders aged between 16 and 20 years, who were to be schooled ‘in the language and literature and in the fear of God’.

The same year the company dispatched two ships, which sailed northwards along Greenland’s west coast. They traded with Greenlanders en route, acquiring several narwhal tusks.

At some point the expedition kidnapped two Greenlanders, who were tied to the ship’s mast. But when they were untied while the ship was in the open sea, both Greenlanders jumped over board and tried to swim back, undoubtedly without success.

Last 17th century kidnapping

The last Danish kidnapping in the 17th century occurred in 1654.

A high-ranking land steward, Henrik Müller, was granted a Royal charter in 1652 to explore Greenland; he sent a total of three expeditions with the Dutchman David Danell as commander-in-chief.

All three expeditions traded with the Greenlanders they met along Greenland’s west coast, acquiring a considerable quantity of narwhal tusks.

On the last expedition the crew tricked six Greenlanders into boarding the ship somewhere in the Nuuk Fjord, and sailed off with them.

A young boy got free and jumped over board, and an elderly woman was put ashore.

Portraits painted

The remaining four Greenlanders were sailed initially to Bergen, where their portraits were painted; these portraits can be seen in the Ethnographic Collection of the National Museum in Copenhagen today.

According to Olearius, the four Greenlanders were a 25-year-old woman, Kabelau; her father Ihob, who died during the passage to Copenhagen shortly afterwards; a woman of about 45, named Küneling; and a girl, Sigoka, aged 13.

The three surviving women were taken to Schleswig, where King Frederik III was staying temporarily because of an outbreak of plague in Copenhagen.

As before, the idea was that the kidnapped people would help facilitate trade with Greenlanders, and they were told that they would soon return home.

They were sent back from Schleswig to Copenhagen, where they learnt Danish.

But a doctor, Thomas Bartholin, reported that the Danish climate and ways of living did not agree with them: one by one they died, probably as early as 1658/59, with Sigoka living the longest.

Thus a total of 19 Greenlanders were kidnapped during Danish expeditions in the 1600s, of which 14 survived the journey to Denmark.

Greenlanders demonstrated kayaking and hunting prowess

The bird spear side prong could have been brought to Copenhagen by any one of these four expeditions – either by the Greenlanders, who brought their implements with them, or by the ships’ crews, following trade with Greenlanders.

Sources tell us that the crews returned with tools and implements as well as normally traded products such as skins and narwhal tusks.

Thus the bird spear was not necessarily owned by one of the kidnapped Greenlanders – it could have been a mariner’s souvenir that ended up in the moat at a later time.

There is nevertheless an indication that the bird spear could have belonged to one of the Greenlanders who came to Copenhagen with the first expedition.

In 1605, Bielke described the kidnapped Greenlanders’ implements and their use at length following observations that he made when the Greenlanders demonstrated their implements and skills for him; this could very well have taken place at the fortifications near Copenhagen’s old East Gate, on the edge of today’s Kongens Nytorv.

The side branch probably broke off a bird spear during the demonstration and ended up in the moat.

A cruel story

Although more than 400 years have passed since these events, it is not difficult to imagine the despair of the kidnapped Greenlanders, and the stories of their homesickness and desperate attempts to escape are heart-rending.

But it was not just Greenlanders who were treated inhumanely. Several sources describe how seamen who had broken the rules in one way or another were put ashore in Greenland and left there.

The small implement found at Kongens Nytorv thus illustrates a cruel story of some of the consequences of Danish ambitions as a great power.

-----------------------------

This article is reproduced on this site by kind permission of Skalk, a Danish periodical with articles about Danish prehistoric and medieval archaeology, history and related topics.

Translated by: Michael de Laine