More extreme warm days in a warmer climate

Global warming means more warm extreme weather conditions, according to an analysis of more than 140 years of air temperature data from Denmark.

The climate is changing. The Earth is becoming warmer and man-made emissions of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are the predominant reason why.

The theory of how greenhouse gases warm the atmosphere has been the subject of deep and profound scientific discussions. The theory has been challenged and tested, and it has not been possible to reject it given a profound lack of compelling evidence to the contrary.

Understanding temperature variations is a prerequisite for understanding patterns of global and regional climate change. Variations in observed temperature around the world and through time allow us to map these areas where we have trustworthy and systematic temperature measurements.

Understanding this allows us to assess the conditions for the future, and make projections of variations and extremes in both warm and cold weather.

Read More: Climate Change theme on ScienceNordic

An example from a Nordic nation

In Denmark, the Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI) has observing stations distributed around the country, providing a unique opportunity to analyse temperature change since the 1870s.

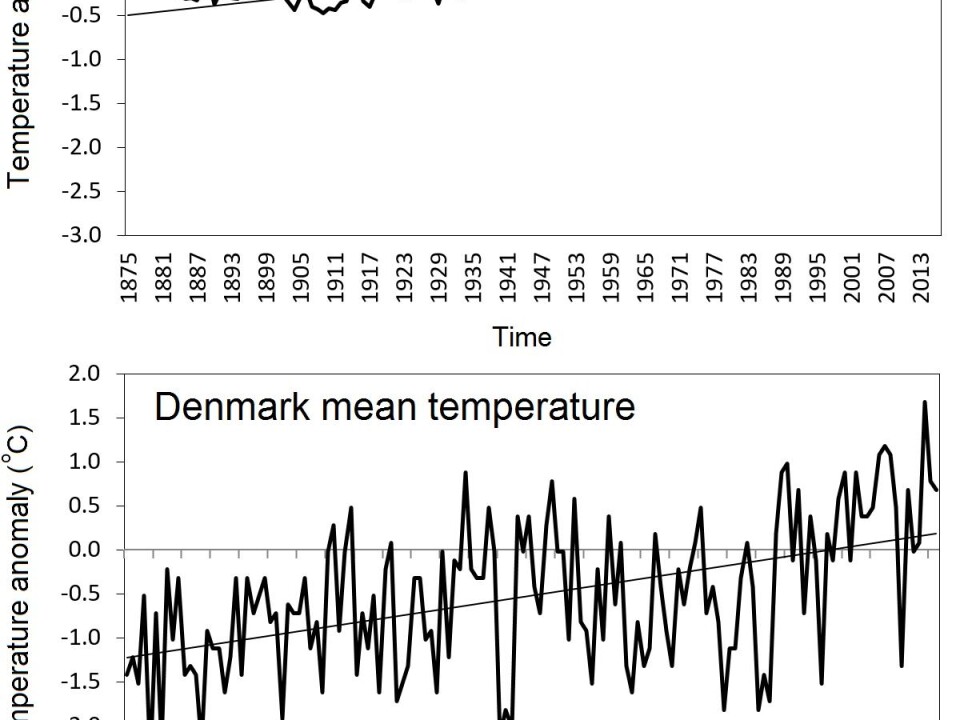

Five of these stations date back to around 1875. This means that we can track temperature changes in this part of the world at a time when industrialisation was expanding throughout the country. It also includes global trends, such as a period of relative warmth in the 1930s and 1940s and the modern global warming that we are witnessing today.

But what else can the temperature data from just one country tell us about modern day climate change?

Data from DMI’s five stations show that Denmark’s mean temperature (measured two metres above the surface) has increased by 1.4 degrees centigrade since 1880. This is a bit higher than the global mean temperature rise of 1.2 degrees over the same period, according to NASA.

Unsurprising, the highest temperatures occurs during the northern hemisphere summer between June and August. Here, the difference between the daily maximum (daytime) and minimum (night time) temperatures, and the difference between the highest and lowest mean monthly temperatures are both at their lowest.

These differences are by contrast, relatively large in the winter, between December and February. And it is the winter night time temperatures that have risen the most since 1875.

Read More: What makes the climate change? Part one

The temperature record

Northwest Europe experiences a range of temperatures as the weather comes from multiple directions. In Denmark, it switches between low pressure systems from the west that form over the Atlantic Ocean and their associated frontal systems, and dry air masses from the east influenced from the large Siberia land mass.

A country like Denmark covers an area of approximately 43,000 square kilometres, which corresponds to about one twelve thousandth of the surface of the Earth—or the size of a mobile telephone in relation to an average sized apartment.

So it should not be a surprise that such a small area can experience unusually cold temperatures while the Earth in general continues to warm.

Denmark has a record of reliable and systematic temperature observations dating back to around 1875, which means that we can map the spatial and temporal trends in temperature. From this record, we know that temperatures span a staggering 68 degrees centigrade: the highest (36.4 degrees centigrade) and the lowest (minus 31.2 degrees) temperatures measured occurred in 1975 and 1982, respectively.

Read More: New report: how the Arctic will look in 30 years

Temperature extremes

Extreme temperatures are those that are either much higher or much lower than the average.

Typically, cold extremes are defined as the coldest ten per cent of observations over a certain time period, which are typically measured at night (daily minimum temperature). The top ten per cent are often defined as extreme warm temperatures, typically measured during the day (daily maximum temperature).

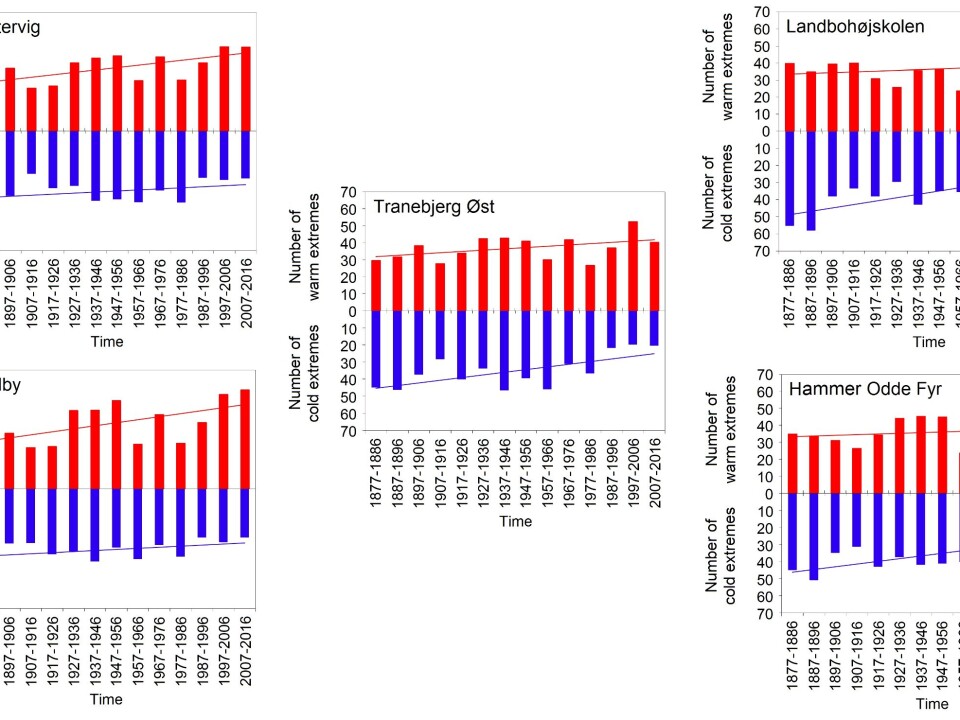

In Denmark, while the number of cold extremes recorded since the 1870s has declined, the number of warm extremes has increased. The development is shown on the graphs below.

This same pattern of fewer extreme cold days and increasingly frequent number of extreme warm days is further observed elsewhere, for example in Greenland.

Read More: Nordic project will solve a riddle of dramatic climate change

Year to year variations

These overall trends include a wider range of variation from one year to the next. For example, 1879 was a record year in terms of the number of extreme cold days—as many as 100 were recorded at one station. While in 1947, four stations recorded a record high number of extreme warm days—as many as 107 days.

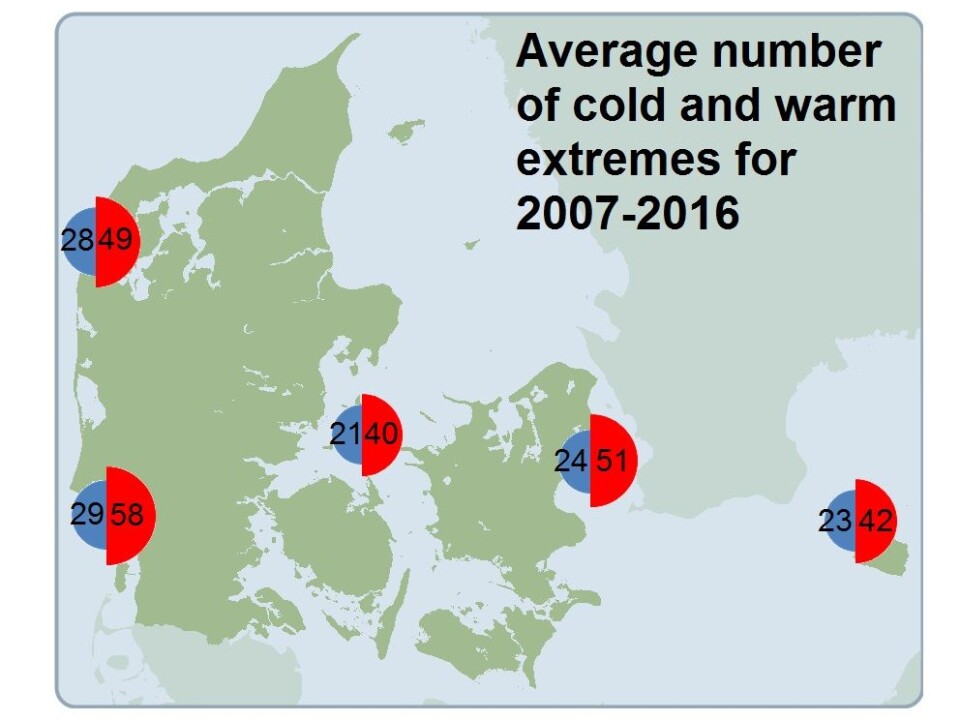

But overall, the past decade (2007 to 2016) was the warmest on record. Here, all five stations recorded between 21 and 29 cold extreme days, and 42 to 58 warm extreme days.

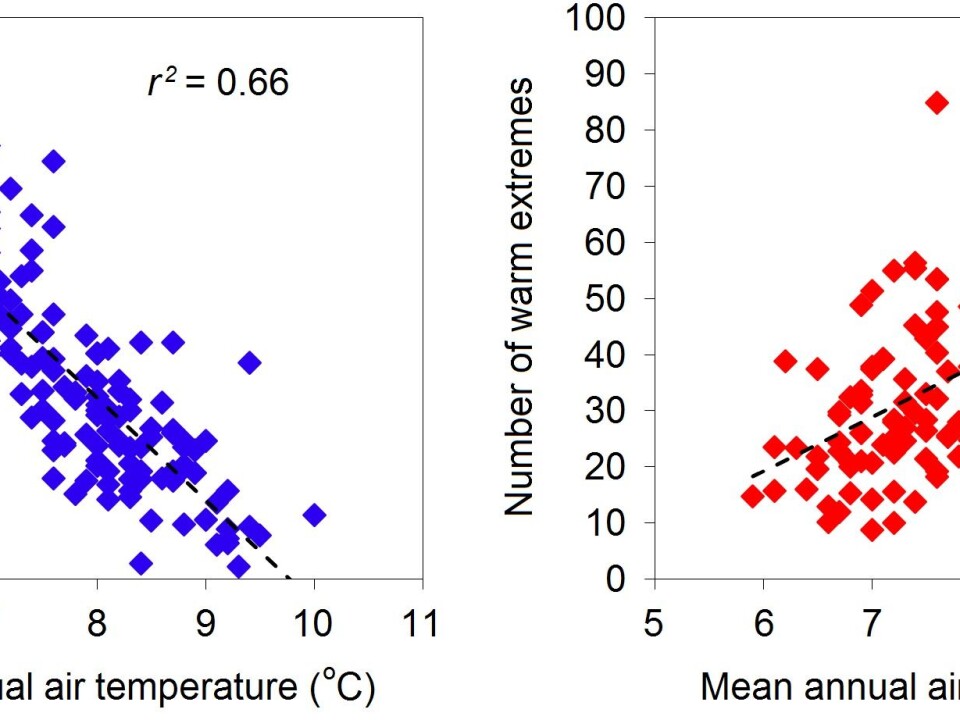

The data show that the number of days with extreme cold or warmth follow the average temperature. Cold extremes occur more often during periods when the average temperature drops, and warm extremes likewise increase as the average temperature goes up.

But this hides even regional variations. The number of cold extremes have declined most towards the east of the country, and especially so in the capital, Copenhagen. Here, there are now 21 fewer extreme cold days than there were 100 years ago. This is partly related to increasing urbanisation, which leads to warmer night time temperatures as buildings and paved surfaces store heat gained during the day more efficiently than do forested or open field areas and release it at night, keeping their surroundings relatively warm.

Read More: Heavy summer rain in Greenland speeds up ice melt

Warmer atmosphere causes more extreme temperatures

Climate scientists expect that the frequency, effects, distribution, and duration of warm extremes will continue to increase in the future as the Earth becomes warmer, while the occurrence of cold extremes is expected to decline.

Our analyses of the temperature extremes in Denmark since 1875 confirm these expected regional trends.

What can be concluded? A warmer atmosphere leads to more extreme warm temperatures in Denmark, and likely in the world around us.

How have temperatures changed where you live? Find out by visiting the website for your national meteorological institute. Many institutes have past climate data freely available for the public to browse.

---------------

This article was originally published on Aktuel Videnskab.

Read this article in Danish on ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk.

Translated by: Catherine Jex