New report: how the Arctic will look in 30 years

The Arctic climate is entering a new state, say the scientists behind a new pan-Arctic report. But implementing the Paris Climate Agreement in full could stave off some of the biggest changes post 2050.

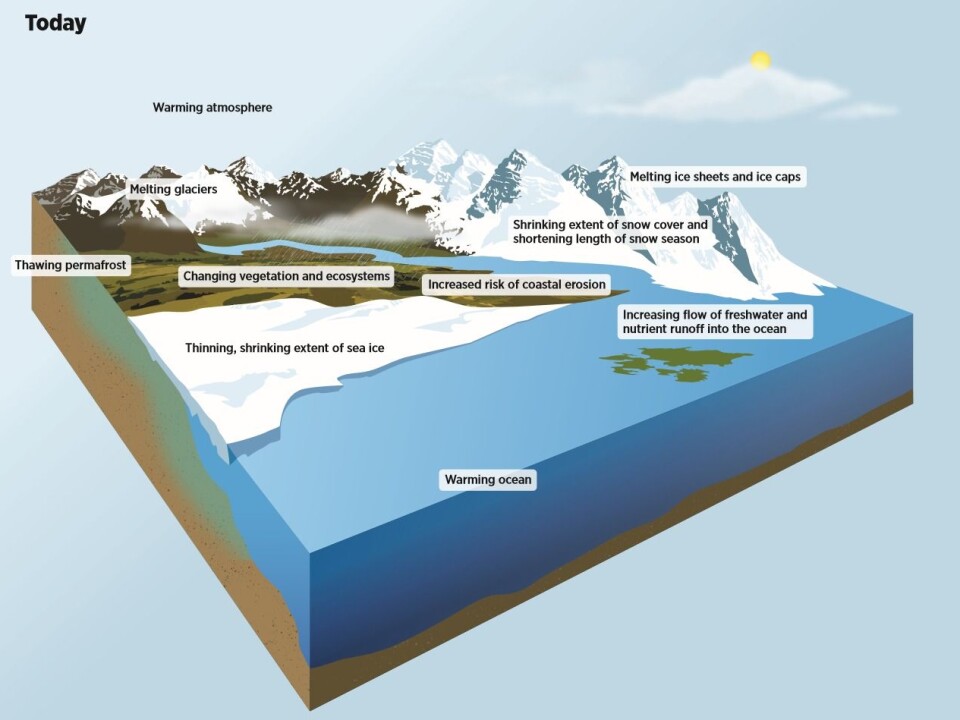

Since 2011, sea ice has reached new lows. Glaciers, and ice sheets have retreated faster than ever. Sea level is expected to rise more by the end of the century than was predicted just a few years ago. The Arctic Ocean is becoming fresher and warmer. Permafrost continues to thaw. And ecosystems are being pushed to new limits.

The Arctic as we know it, is disappearing fast.

These are some of the key conclusions of a new peer-reviewed report published today, which documents changes to the Arctic in recent decades and presents the most complete picture of climate change in the Arctic to date.

Record warming is pushing the Arctic into an entirely new state and the changes are happening faster than predicted, say the scientists behind the report.

“With each additional year of data, it becomes increasingly clear that the Arctic as we know it is being replaced by a warmer, wetter, and more variable environment. This transformation has profound implications for people, resources, and ecosystems worldwide,” write the scientists in the new report.

Unless politicians implement the 2015 Paris Agreement immediately and in full, then a large part of the Arctic as we know it today could be gone by the end of the century, they conclude.

Read More: New study reveals how climate change will overturn nature

Colleague: “A comprehensive overview of Arctic climate”

The “Snow, Water, Ice, and Permafrost in the Arctic” (SWIPA) report was produced by scientists from the eight member states of the Arctic Council, as part of their Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). This includes scientists from Denmark and Greenland, Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

The report provides “a comprehensive overview of the present state of Arctic climate and its development over recent years and decades,” says Professor Marit-Solveig Seidenkrantz, a climate scientist from the Arctic Research Centre at Aarhus University, Denmark.

The report can inform all levels of society, including politicians, educators, and other scientists, says Seidenkrantz, who was not involved in producing the report.

Read More: Arctic sea ice is approaching the limit of natural variability

Big changes in the last six years

The report presents the latest scientific results published since the last SWIPA report in 2011 and describes the changes that are already under way in the Arctic.

This includes new data from Danish monitoring stations and networks across the Arctic, including the PROMICE network that monitors ice loss from the Greenland ice sheet, and the three stations of the Greenland Environmental Monitoring Program.

The SWIPA scientists report that the Arctic is now warmer than at any other time since 1900.

“Temperatures have continued to rise in the Arctic, in fact they’ve risen more than twice as fast as the average for the rest of the world,” says Morten Skovgaard Olsen from the Danish Ministry of Energy, Utilities, and Climate. Olsen was the chair of both the 2011 and the new SWIPA report.

“Snow continues to melt with a loss of around 3 snow days per decade over the Arctic and with big impacts on the ecosystem. Permafrost continues to thaw and the southern boundary has moved north, which has big impacts on infrastructure in Russia, and Alaska and northern Canada,” says Olsen.

Read More: Nordic project will solve a riddle of dramatic climate change

Almost 40 per cent of sea level rise from the Arctic

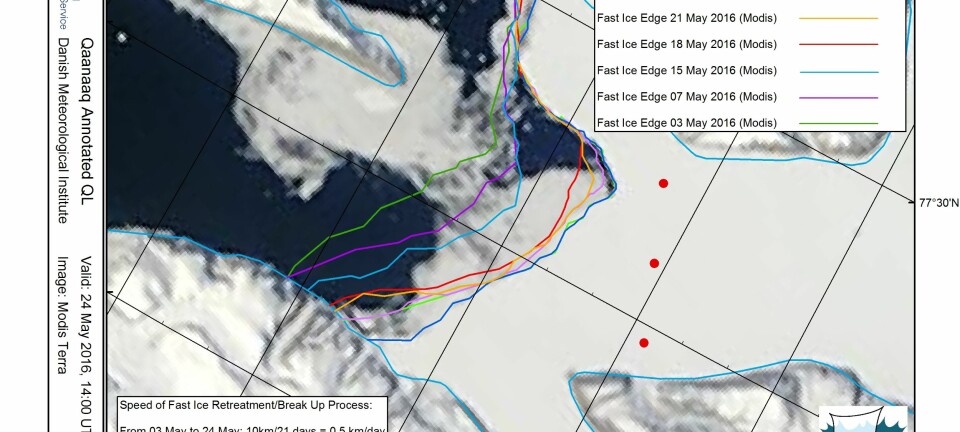

Since the last SWIPA report, sea ice and land ice have continued to decline. Sea ice is now 65 per cent thinner than it was in the decades before 2011 and the extent of both summer and winter sea ice has hit new lows since the last report.

“We have reviewed more than 300 new scientific publications on land ice. So we have a much clearer picture now,” says one of the report authors Jason Box, a glaciologist with the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS).

The report includes new analyses to figure out how much sea level rise has come from the loss of land-ice throughout the entire Arctic region.

“This is the first time we’ve partitioned the Arctic contribution to sea level rise, not only going forward but also looking into the past, back to 1850,” says report author William Colgan, a glaciologist with GEUS.

Collectively, melt from glaciers, ice sheets, and ice caps in the Arctic now accounts for almost 40 per cent of global sea level rise, says Colgan.

“Sea level has risen 28 cm between 1850 and 2017. Of this, Arctic land ice has contributed 12 cm. That’s really showing that the Arctic has been a big player, back to 1850,” he says.

A list of other key changes can be found at the end of this article.

Read More: Sea level rise: How far and how fast?

In the next 30 years, the Arctic will shift to a new regime

The report also projects how the Arctic is likely to continue to change in the coming decades.

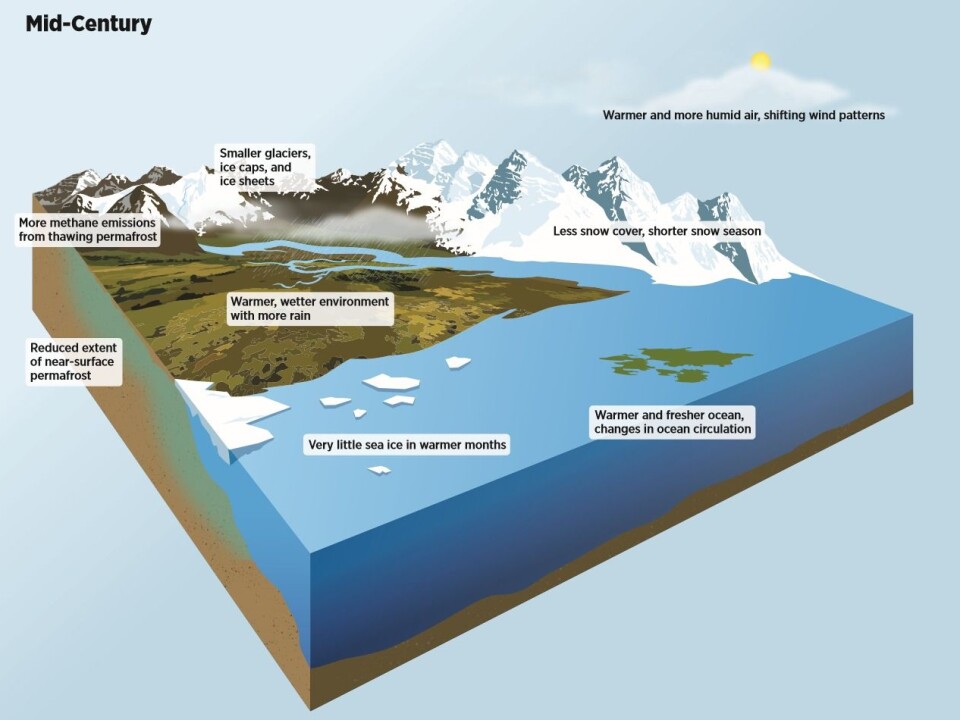

In 30 years time, the Arctic is projected to be four to five degrees warmer than it was at the turn of the century, with continued decline in snow and permafrost.

They confirm that in as little as two decades, the Arctic Ocean is expected to be ice-free in summer. This is earlier than many climate models predict, say the SWIPA scientists and represents a new type of Arctic environment.

Seidenkrantz is not surprised by these conclusions.

Data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center in the USA suggests that the Arctic Ocean could be ice free in summer sometime between 2030 and 2050, says Seidenkrantz.

“But on average sea ice extent has decreased much faster in recent years, and when you consider not only sea ice extent but also sea ice thickness and the distribution of multiyear sea ice, the decrease has been very fast in recent years,” she says.

However, both Seidenkrantz and the SWIPA scientists point out that there is still not enough data to make a more precise prediction, since sea ice varies so much from one year to the next.

Read More: When will the Arctic be ice free?

Implement Paris Agreement and avoid the worse

These mid-century changes are now locked in to the climate system due to the amount of greenhouse gases that are already in the atmosphere and the heat already stored in the ocean, according to the report.

But reducing emissions now, could lessen the changes expected by the end of the century.

“We recommend an early, ambitious, and full implementation of the Paris Climate Agreement, and we need to prioritise research that will improve our predictions of change and their Arctic and global consequences” says Olsen.

Implementing the Paris Agreement to reduce greenhouse gases could stabilise Arctic warming post 2050, say the scientists.

This could limit Arctic warming to five degrees Centigrade by the end of the century, and avoid the additional five degrees rise that is projected if emissions continue at their current pace.

Read More: COP21 agreement is unclear and unrealistic: scientists

Sea level will rise more without emission cuts

Whether or not we adopt the Paris Agreement also has big impacts on projections of future sea level rise.

New analyses by SWIPA scientists updates the previous projections of sea level rise by the end of the century. The new projections include additional melt processes that were not included in previous projections in the most recent UN IPCC report in 2013.

“We now know of other processes affecting the Arctic--additional processes melting the Greenland ice sheet--for which new observational evidence has emerged since the last report,” says Colgan.

They find that implementing the Paris agreement in full could limit sea level rise to 52 centimetres by the end of the century. Not implementing the Paris Agreement in full will lead to at least 74 centimetres of sea level rise, say the scientists. Up to 25 centimetres alone could come from melting land-ice in the Arctic.

These new estimates are higher than the lower end of the previous projections by the IPCC, due to the inclusion of these new processes and the additional observational data that is now available.

Read More: Time is running out to adapt to dramatic sea level rise

Scientists remain optimistic despite political uncertainty

The need to cut greenhouse gas emissions should not come as a surprise, says Seidenkrantz.

“If we want to keep Arctic warming at a reasonable level, the Paris Agreement and a lower greenhouse gas emission scenario must be implemented. I don’t think that it’s controversial. However, it is of course not an easy process,” says Seidenkrantz.

But making this a reality is still an up hill struggle. So far, the agreement has been ratified by 143 out of 196 of the countries who originally signed up. And one of the biggest greenhouse gas emitters, the USA, are now considering whether to pull out of the agreement altogether.

“It will take a while from implementing the decision to seeing the benefits. This can make it difficult,” says Colgan.

But Seidenkrantz remains positive.

“Although it is probably optimistic to assume a global implementation of the Paris agreement any time soon, not least with recent political changes in the USA, overall we are moving in the right direction,” says Seidenkrantz.

“Luckily more and more governments and enterprises are becoming aware of both the economic benefits of developing green technologies and the enormous economic, environmental, and health costs that global warming, changing climate, and increased sea level will mean,” she says.

The SWIPA report will be published today at the AMAP International Conference on “Arctic Science: Bringing Knowledge to Action” in Reston Virginia, USA. The findings will help advise the UN’s IPCC to produce their next assessment report in 2022.