Fossil DNA reveals new theory on colonisation of America

New theory: The first Americans could not have migrated via the ice-free corridor as most scientists believe.

Fossil DNA from the bottom of a Canadian lake shows that the first humans to colonise America could not have followed an ice-free corridor in Alaska and Canada, as many scientists suggest.

“Now we can kill a theory that people have been proposing for more than a hundred years. It’s significant to understanding both our own history and that of animals,” says co-author Professor Eske Willerslev, head of the Centre for Geogenetic Research at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Willerslev suggests that the first Americans followed an alternative route, possibly a thin strip of land along the west coast of Alaska.

“This research provides the most complete picture yet of the timing and pattern of plant and animal development in a central ‘bottleneck’ region of the ice-free corridor,” writes Suzanne McGowan, from the University of Nottingham, UK, in a commentary for Nature.

The new method used in the study to analyse fossil DNA from environmental samples is a revolution in exploration of ancient and complex biological life in sediments, writes McGowan.

The new results are published in the journal Nature.

The first Americans found a wonderland

A group of modern humans left Africa somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago and in a relatively short time managed to colonise Australia, Europe, Asia, and finally America via Siberia.

The first human inhabitants of the Americas would have met a cornucopia of large animals such as bison, mammoth, horses, glyptodonts (a large armadillo-like animal), crocodiles, and the giant sloth.

But just how these immigrants made it to America in the first place continues to puzzle scientists.

Read More: Kennewick Man’s genome suggests Native American ancestry

Old theory: Humans followed an ice-free corridor to the Americas

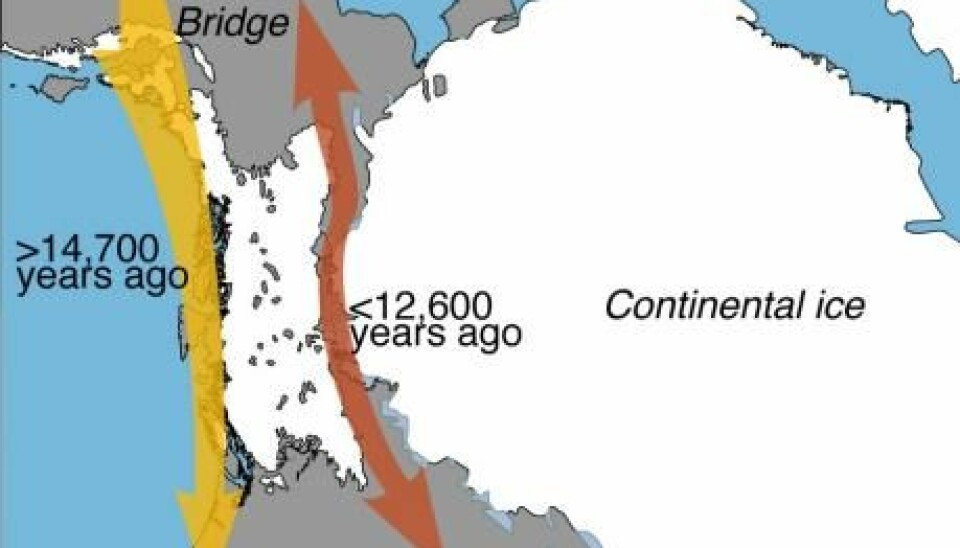

The old theory says that humans first made it to America via the Bering land bridge that connected Siberia and Alaska. During the Last Ice Age, access to the bridge was blocked by two large glaciers.

This corridor first became ice-free sometime between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago at the end of the Last Ice Age, when two large glaciers retreated and is therefore referred to as the ice-free corridor (See the map in the gallery above).

“If you look in a textbook, they always draw an arrow between Siberia and Alaska and down through the ice-free corridor, and then show people spreading south,” says Willerslev.

But this classic interpretation was challenged by discoveries of human remains throughout North America and South America that date as early as 14,700 years ago. Many have speculated that there simply is not enough time for the first Americans to colonise that far south if they had followed the ice-free corridor just 300 years earlier.

Read More: DNA links Native Americans with Europeans

Plant and Animal DNA holds the answer

Willerslev and lead-author Mikkel Pedersen, a postdoc at the Centre for Geogenetics, University of Copenhagen, set out to test the hypothesis by establishing when the first plants were able to grow in the new ice-free corridor. This indicates exactly the moment when humans would have been able to survive the 1,500 kilometre long journey.

“Everyone expects that animals and people went through this corridor, but in reality we know very little about what the biology was like--it could have just been a mud hole,” says Willerslev.

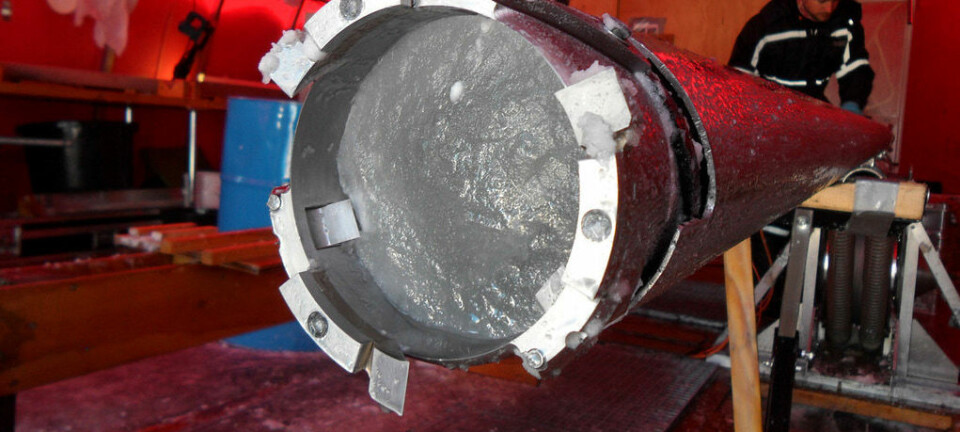

They collected cores of sediments from lakes in the area that date back to this time. In the cores they found plant fragments that could be radiocarbon dated and characterised the type of vegetation that would have existed by analysing pollen.

Willerslev and Pedersen also developed a new technique to map all the DNA in the sediment samples.

“We made a meta-genome analysis. That means that we looked at all the DNA that there was, and we got everything from bacteria, protozoans, and mushrooms, up to plants and animals. It gave a fantastically detailed picture,” says Willerslev.

Read More: Facial mites reveal where you come from

Ice-free corridor not ice-free until 12,600 years ago

Both pollen and DNA analyses agreed that the first plants appeared 12,600 years ago and animals arrived shortly after. Traces of perch and pike indicate that the lake ecosystem developed quickly.

The first land animals were Bison, followed by hare, water voles, and mammoths.

One thousand years after the ice had retreated and the ice-free corridor had opened up, the area had turned into patchy forest and new comers such as stags had arrived. Later, the forest developed into a denser, coniferous forest, which was then inhabited by moose.

“Everything fits really well and what is really incredible to me is the detailed knowledge of animals that we obtained,” says Willerslev.

“But the most important take-home message is that it is now very unlikely that people could have crossed the ice-free corridor before 12,600 years ago,” he says.

Read More: Ice Age Europeans migrated back to Africa

The first Americans must have taken another route

This means that the earliest human arrivals must have travelled by another route.

“Honestly, we don’t know which route they took, but most likely they followed the coast,” says Willerslev.

Geologists have identified a narrow strip of land along the Alaskan coast which humans and animals could have followed to enter America. The land strip is now underwater, but a number of small islands along the way could still hold evidence of their journey.

Alternatively people could have made the trip by boat, hugging the coast, dodging icebergs, and living off fish and seals as the Inuit do today.

-------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Scientific links

- Postglacial viability and colonization in North America’s ice-free corridor. Doi:10.1038/nature19085