When feeling sick feels great: New study reveals a close link between reward and unease

A recent study shows how mice can be made to prefer sickness, nausea, and stress over feeling well, just be removing one specific receptor from the brain. This could open the door to new treatments against various types of malaise associated with disease.

Imagine that by using a nasal spray, which blocks the signal from a single receptor, you suddenly find that nausea, stress, and the common cold no longer feel so unpleasant… they might even feel great.

Most of us have been sick at one point or another with the flu or the common cold, or have experienced nausea or stress, and most of us would probably agree that these are not particularly enjoyable. A scenario in which you could actually enjoy these conditions might sound like something out of a science fiction movie, but my recent research has shown that it could soon become a reality.

Mice preferred a room associated with sickness

I just completed my PhD studies in neuroscience at Linköping University in Sweden, and during some of my experiments, I found that mice missing a specific receptor in the brain developed a preference for a room in which they had been sick, over another room where they felt fine. We gave the mice in the “sickness room” a compound that briefly induced influenza symptoms.

I was flabbergasted; it was completely surreal to observe this behaviour. The mice kept searching for the room where they had felt sick, and not the room where they felt fine. They behaved as if they had experienced something extremely positive, equivalent to what can be seen with normal mice that have received rewards like Nutella, or drugs, such as alcohol or cocaine. I couldn’t believe my own eyes, fortunately my colleagues saw the same behaviour.

Mice preferred feelings of nausea and stress

It turned out that these mice not only preferred the feeling of sickness, but also nausea and stress. We needed to know if this behaviour was a reaction to inflammation or if it was a general mechanism also related to other types of negative stimuli.

So, we tested the reactions of these mice towards various compounds, which mimic disease symptoms that we would like to be able to treat in human beings. While normal mice will avoid the room where they felt malaise, the mice missing the specific receptor kept returning to it.

Our discoveries were recently published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Receptor determines how the mice react to aversive events

These seemingly sickness-loving mice were missing something called the Melanocortin 4 receptor. This receptor is commonly present in various areas throughout the brain. For instance, we know that the Melanocortin 4 receptors in the hypothalamus area of the brain are responsible for signaling satiety towards food, but we don’t yet know what function they serve elsewhere in the brain.

One of the brain areas, where the Melanocortin 4 receptor function has not been fully studied, is the brain’s reward center, called the striatum. This area is particularly important for our ability to evaluate various stimuli in our surroundings as either rewarding or aversive.

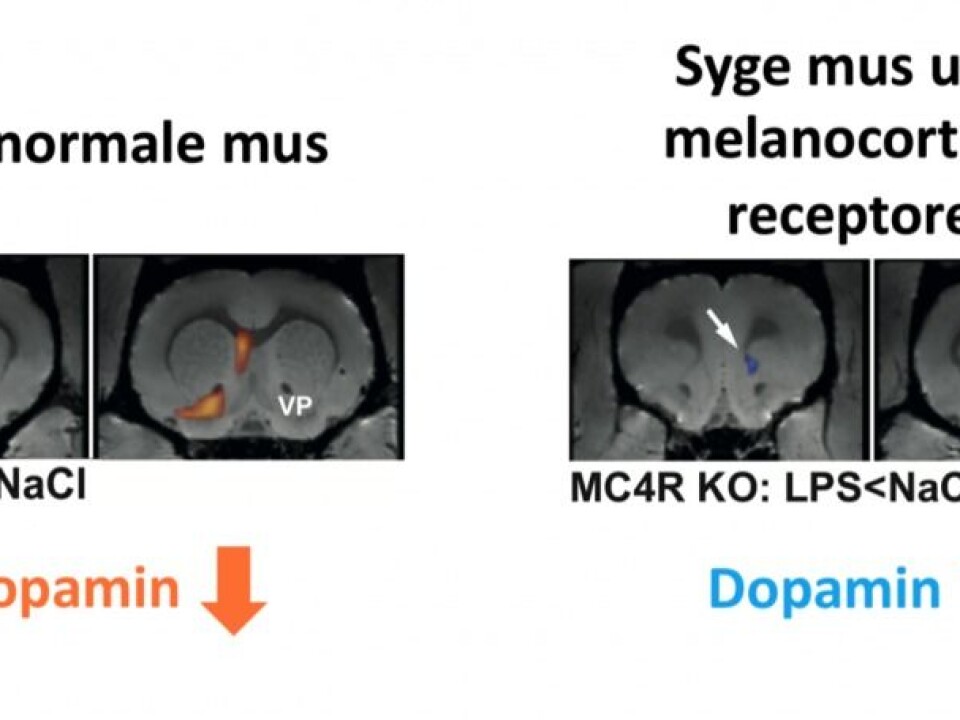

The striatum is able to do this by regulating the level of dopamine in the brain. A high dopamine level in the brain helps us assign positive value to things that are good for us (such as food and drink, friendship, sex), while a low dopamine level signals that something should be perceived as bad and is to be avoided (for example, acute danger, disease, or pain).

Read More: Mice experiments explain how addiction changes our brains

A reverse response to dopamine

But what happens in the brain of the mice missing the Melanocortin 4 receptor, since their understanding of aversion is turned upside down?

We found that what causes the mice to search for places where they previously felt discomfort, is the signaling of a certain type of nerve cells in the reward center of the brain.

When mice lack the Melanocortin 4 receptor from these specific nerve cells, they develop an inverted dopamine-response towards negative stimuli. This means that where normal mice experience decreased dopamine in several brain areas when sick, the mice missing the Melanocortin 4 receptor do not experience this decrease. Instead, they have increased dopamine levels.

An elevated dopamine-level in this particular way is usually directly connected with positive experiences and reward, which could explain why the mice prefer aversion over feeling well.

Read More: Space travel changes gut bacteria in mice

A general mechanism of the mammalian brain?

The incredible thing about these discoveries is the implication they carry; that a specific receptor type on a single cell population determines how adverse events are encoded in the brain of mice.

This could potentially illustrate a general mechanism of the mammalian brain whereby pleasure and aversion are so tightly linked that our perception of good and bad is determined by the signal of a single receptor.

We still need to explore if this mechanism is present in human beings in the same way as it is in mice. But it could well be, as our reward system is extremely similar to that of mice. The idea that the brain has a mechanism, which can easily change the encoding of aversion or reward, could represent an evolutionary advantage in an environment with many challenges and variable stimuli.

Read More: Painkillers lower fertility in mice

Nose spray makes the mice seek malaise

But to return to the science fiction scenario from earlier. To see whether the Melanocortin 4 receptor could be a target for a universal treatment against various types of malaise, we needed to test a pharmacological intervention in normal mice with intact Melanocortin 4 receptors.

We found that by giving normal mice a treatment to block the receptor-signaling, it not only prevented malaise and aversion towards the unpleasant conditions, it also made the normal mice prefer them.

In this way the results in normal mice receiving the treatment was similar to that of the mice lacking the Melanocortin 4 receptors. The normal mice received the pharmacological intervention with a nasal spray, and immediately developed more positive behaviors towards sickness.

Read More: Breakthrough: How the brain keeps track of time

A future treatment?

These results are encouraging, and perhaps the Melanocortin 4 receptors could eventually form the basis for new treatments against a wide range of diseases characterized by discomfort, malaise and pain, such as inflammatory diseases like cancer and arthritis.

But, there is still so much to explore when it comes to understanding how the brain encodes our feelings of reward and aversion.

The results from this study has demonstrated that the two phenomena are more closely linked in mice than previously assumed, which hopefully will make it possible to find the same mechanism in human beings. If we can do this, then we may well be able to develop better treatments against diseases characterized by malaise and depression.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

Scientific links

- 'Motivational valence is determined by striatal melanocortin 4 receptors', The Journal of Clinical Investigation (2018), doi: 10.1172/JCI97854

- Anna Mathia Klawonns profile, PhD at Linköping University