Aalborg University scientists: world renowned for causing pain

Scientists return to Denmark every year to study what happens in the body when we feel pain.

Imagine coming into contact with high concentrations of capsaicin—an active component of chili pepper—injected underneath your skin. It hurts.

Yet, volunteer trial participants willingly subject themselves to this burning sensation.

Other participants receive a shock from salt-water or a nerve growth factor injected into their muscles to simulate the sensation of a muscle injury.

The research attracts a constant stream of scientists from outside Denmark. Among them is Siobhan Schabrun, an Australian scientist who studies how musculoskeletal pain influences the brain. She has visited Aalborg University many times—most recently to study a method in which trial participants are subject to prolonged muscle pain.

“The method developed at Aalborg University enables us to induce week-long pain in healthy people. Clinically speaking, the pain is similar to what you experience with tennis elbow,” says Schabrun, senior scientist at Western Sydney University, Australia.

Read More: Scientist will decode neuron messages to treat pain

Method simulates long-term pain

The method is developed by one of the university’s pain research centres: the Center for Neuroplasticity and Pain (CNAP), led by Professor Thomas Graven-Nielsen.

As part of their research, scientists inject a nerve growth factor (NGF) into the muscles to simulate a long-term injury.

They hope to discover how chronic pain influences the central nervous system.

Associate Professor David Seminowicz, head of the Pain Imaging Lab at The University of Maryland, USA, is one of the centre’s visitors. He is also interested in learning more about how chronic pain influences the brain’s neural networks.

“We know that pain influences various networks in the brain and other connections between neurons, but until now we haven’t been able to study how changes occur over time, from before the injury and how the pain develops afterwards,” says Seminowicz.

The advantage of the methods developed in Aalborg is that they can be used to simulate long-term muscle pain. Scientists can simply give repeated injections of NGF over a prolonged period.

Using another technique—electroencephalography or EEG—allows the scientists to measure the brain’s electrical activity before and after the healthy subjects have experienced pain to see how it affects the brain over time.

Read More: Antibiotics may help with intense back pain

Stunning pain patterns

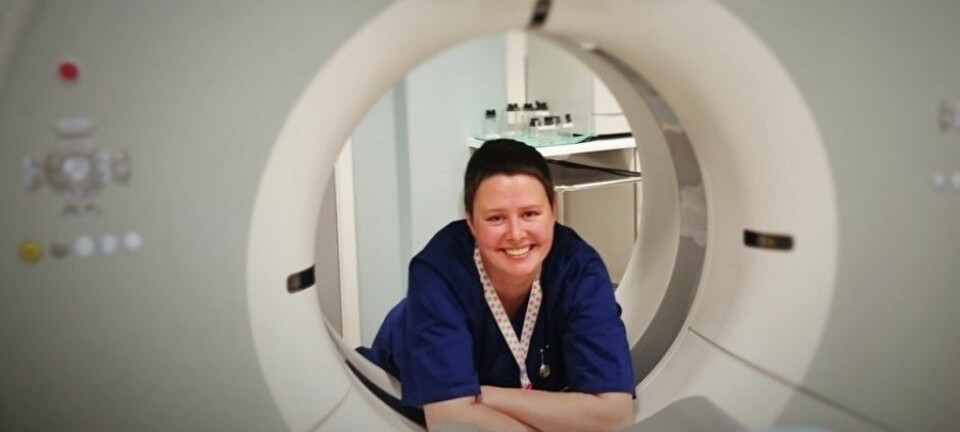

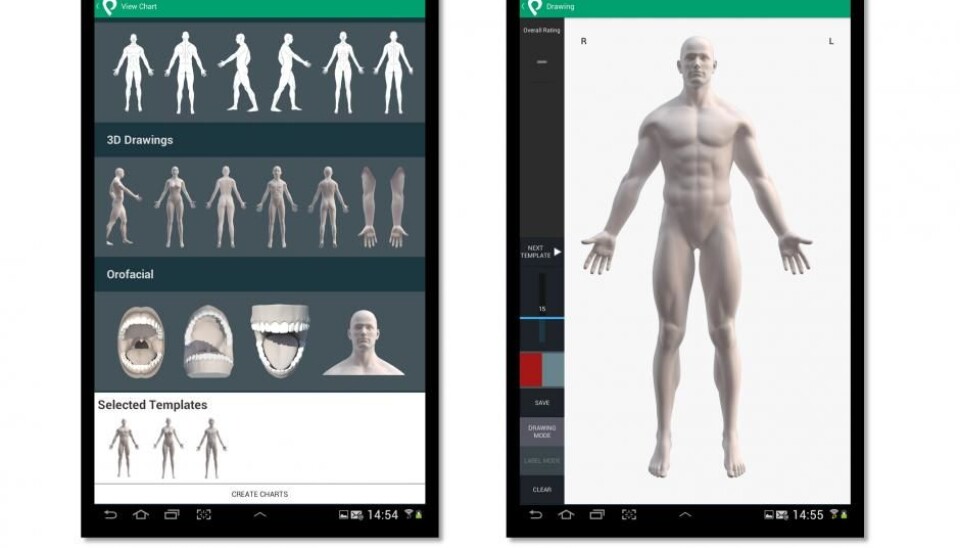

Scientists at Aalborg University do not just inflict pain on trial participants. They also map where and how the pain is felt. Associate Professor Shellie A. Boudreau from the centre asks the patients and trial participants to mark their pain on a number of digital diagrams of the body.

Each diagram depicts the muscular nature of the body.

“It’s unimaginably detailed,” says Boudreau.

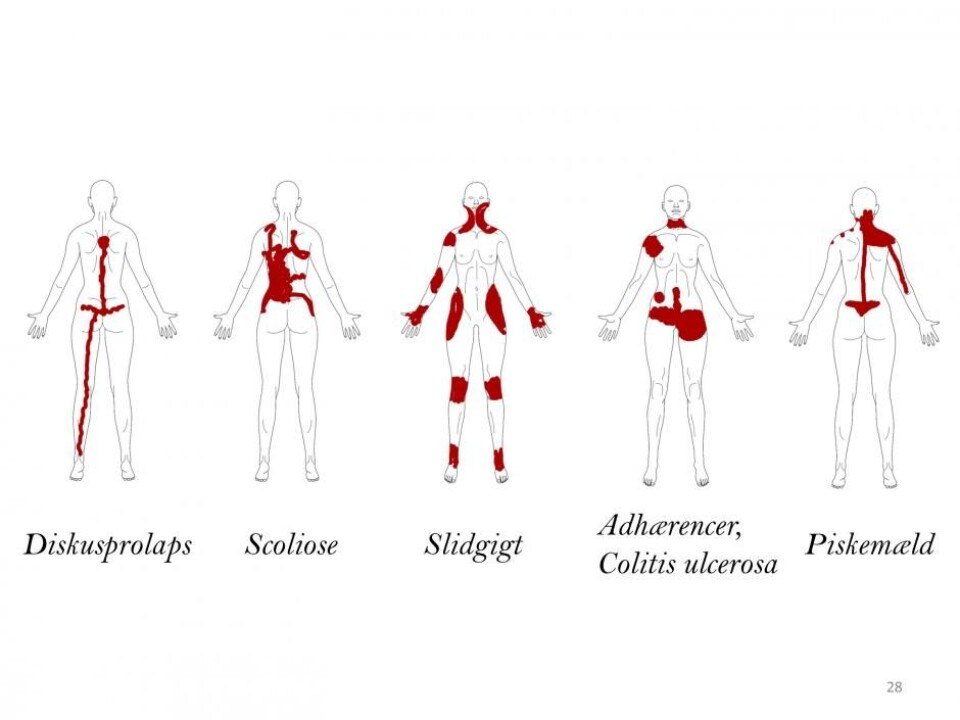

“We ask people to mark on the diagram how they feel the pain and where. This all adds up to some amazing patterns. It’s really fascinating. Sometimes it almost looks like art,” she says.

Read More: What works best for back pain?

Pain is personal

The digital pain maps show that participants who have been previously treated for injuries at some time in their life experience pain that spreads beyond the site of the original injury.

Even though the injury healed long ago, the trials show that an old injury can make the pain system especially sensitive.

By mapping pain, scientists can better understand how pain spreads and becomes chronic, which may ultimately lead to new treatments.

“Pain is very complex and personal and I don’t imagine that we will discover everything and cure chronic pain. But every little step brings us closer,” says Boudreau.

------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex