Your visual experiences remain stable over time

One would imagine that we – without knowing it – see physical objects differently depending on how old we are. But this does not appear to be the case, new study finds.

We get wrinkles and our memory changes as we age, but age does not change our visual experience.

“We wanted to see if brain activity patterns remain stable over time. If I look at my old coffee mug today, will I be having the same visual experience as the one I had of the mug seven years ago?” asks Kristian Sandberg, a postdoc fellow at the Department of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, Denmark.

He is the lead author of the new study, published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience.

”This is not an easy thing to assess. How can I tell? But now we know: I’m probably seeing exactly the same.”

Subjects looked at pictures

The subjects told the computer when they were looking at the striped pattern and when they were looking at the face. The program them checked this data against the way that the subjects’ brains behaved when they looked at the two pictures.

If you tend to philosophise a bit about life, you might believe that our view of the world changes as we grow older – without us being aware of it.

To examine this, the researchers used special computer software and brain scans from four study subjects.

About 2.5 years ago, the researchers presented two different pictures to the subjects, one for each eye. One picture showed a human face, and the other a striped pattern.

”Here, the brain receives two widely different pieces of information at the same spot in the visual field. The brain as no way of blending the images into one single object because the two images are so different,” says Sandberg.

”So the brain needs to make a choice: which of the two objects does it want to focus on? The striped pattern or the face?”

The researchers cannot say which of the two pictures the subjects are seeing before them. Only the individual subject can do that.

Computer decodes conscious perception

By pressing two buttons, the subjects told a computer which one of the two images they were looking at.

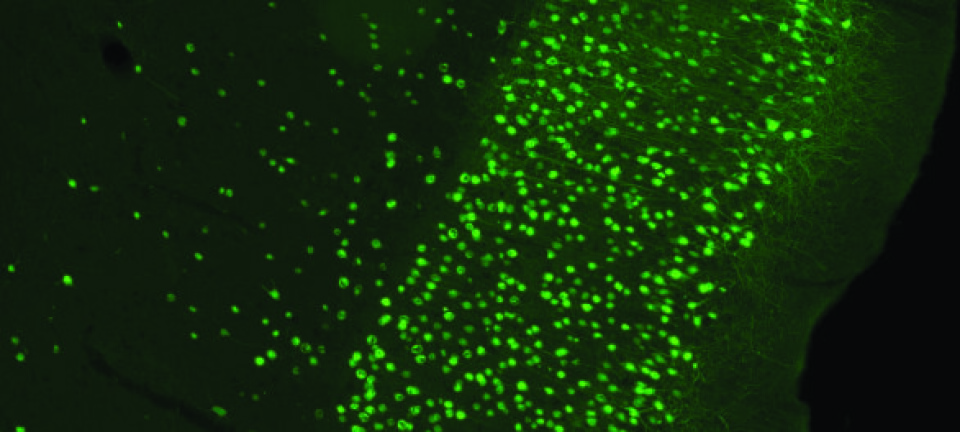

The computer, which was connected to a brain scanner, was then trained to decode conscious perception from neural activity recorded during binocular rivalry using magnetoencephalography (MEG). This technology made it possible to read off the activity in various parts of the brain with an accuracy of half a centimetre and a few milliseconds.

“In this way, we ‘trained’ the computer program. The subjects told the computer when they were looking at the striped pattern and when they were looking at the face. The program them checked this data against the way that the subjects’ brains behaved when they looked at the two pictures,” says Sandberg.

“After a while, the computer had been given sufficient information to predict which one of the two pictures they were looking at, based only on an analysis of their brain activity.”

No changes in visual experiences after 2.5 years

After 2.5 years, the subjects were called in for another brain scan. The same tests were carried out, using the exact same pictures.

It turned out that their perception had not changed. Using the 2.5-year-old data, the computer could easily predict which of the two pictures the subjects were looking at.

A few days later, the experiment was repeated for a third time, with the same results.

”We were surprised to find that there was absolutely no difference when the computer generalised across a couple of days or several years,” says the researcher.

Next step: how do two people’s experiences differ?

The findings demonstrate that the neural correlates of conscious perception are stable across years for adults, but differ across individuals.

Moreover, the study validates decoding based on MEG data as a method for further studies of correlations between individual differences in perceptual contents and between-participant decoding accuracies.

“There appears to be a relatively large variation among individuals. In our upcoming studies we will look at how this variation is related to what each of us perceives,” says Sandberg.

These studies will e.g. shed light on a question that many people have asked themselves: do we perceive colour in the same way? In other words, do you see what I perceive as the colour blue when we are both looking at the same red Ferrari?

----------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk