Adult memory a bellwether of the ageing brain

The memory you have as an adult can help predict how well your brain will work 20 years later.

A Swedish researcher has discovered that individual differences in memory at a young age have a bearing on how well our brains work as we age.

“Our findings show that we can predict how the brain will perform when we get old by testing memory capabilities 20 years earlier,” says Dr Sara Pudas of Umeå Centre for Functional Brain Imaging (UFBI).

Pudas followed more than 1,500 test subjects in three separate studies for periods of 15 to 20 years.

The subjects’ memories were assessed every five years using episodic tests that required them to recall various words and expressions.

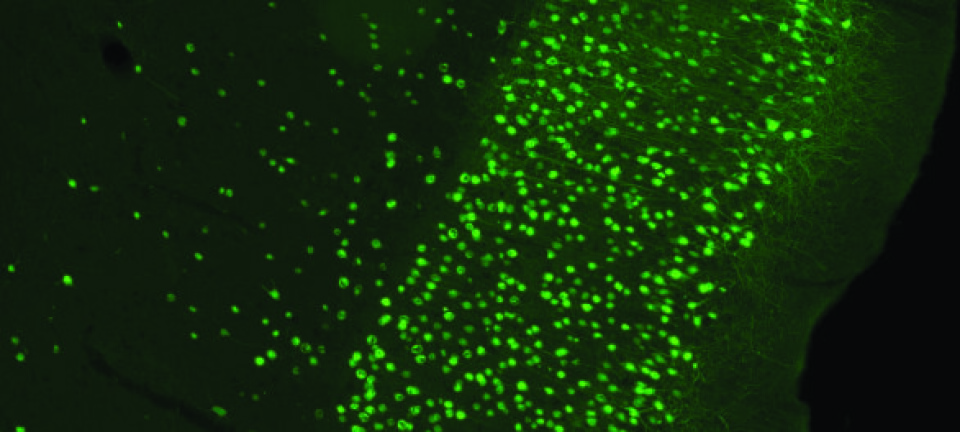

The scientists also examined the brain anatomy and performance of about 400 test participants using functional magnetic resonance imaging (MR).

Shrinking hippocampus

Old age is linked to a reduction of mental ability – especially memory.

“The purpose of this longitudinal study was to chart a normal ageing process. So we compared healthy individuals whose memory was poorer with people who had retained their capacities. We found that memory centres of the brain, such as the hippocampus, are vital in preserving the brain’s functionality,” explains Pudas.

The hippocampus is a small, banana-shaped part of the brain that is essential to learning and memory. It lies deep in the medial temporal lobe of the brain.

In addition to confirming that cognitive decline was tied in with a reduction in hippocampus activity, the researchers saw that this part of the brain gradually shrinks even in healthy older people.

Pudas stresses that none of the test subjects suffered senile dementia or Alzheimer’s.

“Previous studies have shown that the hippocampus shrinks in cases of dementia and Alzheimer’s. This indicates the hippocampus function is important for retaining memory in old age,” Pudas said.

Her results support previous cross-sectional studies that also emphasise the importance of a well-functioning hippocampus.

“Reduced blood circulation and diminished hippocampus activity are also key contributing factors to impaired memory among the elderly,” says Pudas.

Significant individual differences

The results showed broad individual differences regarding cognition loss among the elderly, as some lose memory capabilities gradually and other lose it rather rapidly.

”Our research also showed that some elderly did not lose the same degree of memory function as others. The older people who retained cognitive function actually displayed hippocampus activation on a par with younger adults. Older people with good memories even displayed a higher amount of frontal lobe activation than younger people. These are important discoveries that are in line with previous research that primarily focused on the negative aspects of growing old,” says Pudas.

What characterises people who have good memories, even in old age?

“The loss of memory depends partly on our genetic make-up, but current research shows again how important it is to remain active. This includes physical, mental and social activities. In addition to exercising and keeping the brain fit through various tasks, it’s important to stay in frequent contact with family and friends. Another factor here is that having a higher education, or a complex line of work, appears to bolster brain functions with regard to dementia,” explains Pudas.

Unique study

Not only has Pudas's research made some unique discoveries; it is special because so many test participants were followed for such a long time.

“This gave us the opportunity to see if a high or low performance on tests at a younger age linked to cognitive functionality later in life. Now we’re conducting a follow-up study with test subjects from this project.”

“We want to get a better estimation of this by doing another MR scan to see how the activation of their brains changes as time passes,” explains Pudas.

One of her goals now is to see if the results can be of help in making early diagnoses of dementia.

“Dementia is not just a condition that is an increasing problem in industrialised countries, as the number of elderly grows. It also affects close family members and the whole family. We now have medications that help retard the development of dementia and slow down the destructive changes in the brain – but we cannot prevent its development. This is why it’s so important to get an early diagnosis,” says Pudas.

------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling