Clay tablets from the cradle of civilisation provide new insight to the history of medicine

Ancient “doctors” mixed magic and medicine to heal patients.

Before the Greeks excelled in science and philosophy, culture was blooming in Mesopotamia, located between the Euphrates River and the Tigris River in present day Iraq.

This region, known as the cradle of civilisation, was the seat of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which lasted from around 900 to 612 BCE.

Some historians consider the kingdom to be the first true empire in history and many Assyrian kings and cities are described in The Old Testament.

A Danish Ph.D. student has now analysed clay tablets from the Kingdom’s heyday, in which a man called Kisir-Ashur documents his education to become a doctor, and how he combined magical rituals with medical treatments.

Some of the concepts of illness described by Kisir-Ashur and in other, similar texts, were perhaps handed down to the Greeks.

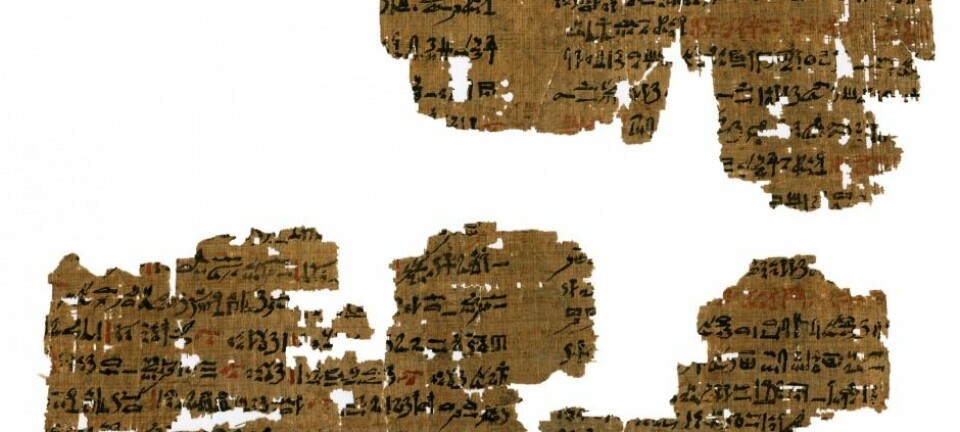

Some of the most detailed sources of ancient medical practices

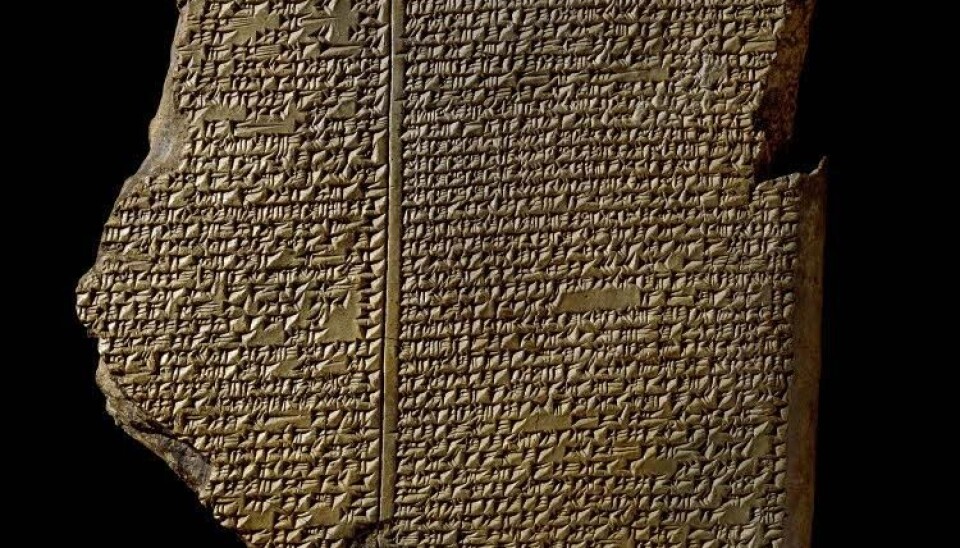

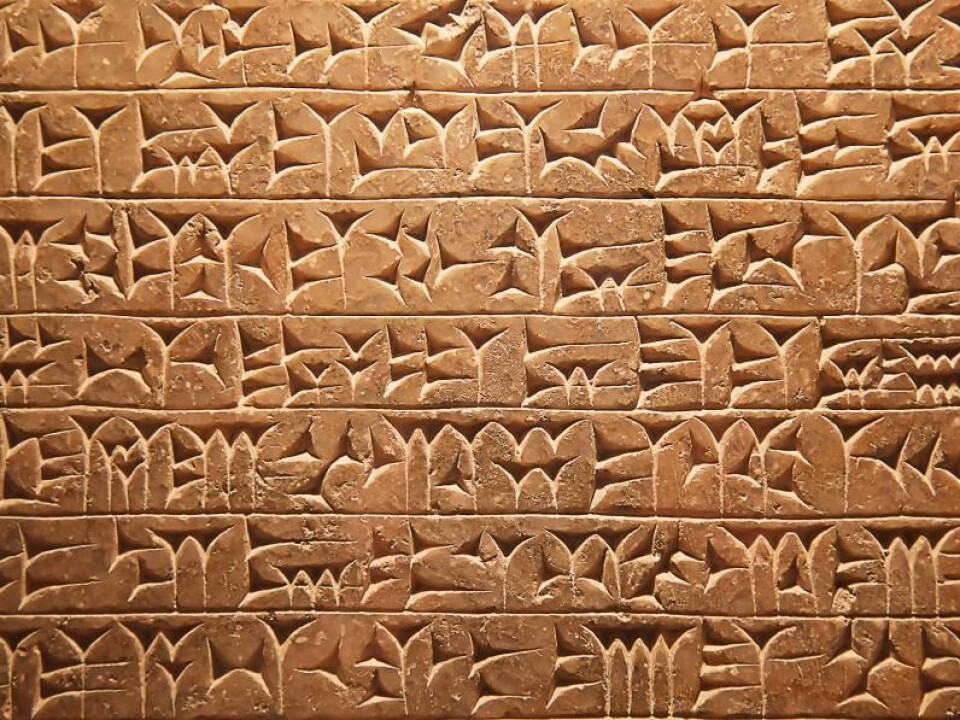

The clay tablets were largely written by Kisir-Ashur at the end of the seventh century BCE. He is one of the earliest examples of a doctor, or at least something like a doctor, in terms of the level of detail of training and practice.

Researchers have known about the clay tablets for decades, but this is the first time that Kisir-Ashur’s writings have been studied together. And they have turned out to be one of the most detailed accounts of ancient medical education and practice ever recorded.

“The sources give a unique insight into how an Assyrian doctor was trained in the art of diagnosing and treating illnesses, and their causes,” says Dr. Troels Pank Arbøll from the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. Arbøll studied the text as part of his Ph.D., which he recently defended.

“It’s an insight into some of the earliest examples of what we can describe as science,” he says.

Illness in Mesopotamia

The residents of Mesopotamia did not distinguish between what we today call magic and medicine. For them, disease was caused by supernatural forces such as gods and demons.

Treatment typically included identifying the illness according to the power that caused it. Then medical agents were applied to heal the disease and its symptoms, alongside rituals to appease the gods.

Some text, which researchers call “medical,” consists of both diagnoses, descriptions of symptoms, prescriptions, incantations, prayers, and rituals.

Disease could be caused by sinful or objectionable behaviour, or it could be the result of witchcraft performed against the patient.

Illnesss was not the only type of divine punishment. Other examples include economic ruin or social exclusion. These problems were treated on the same level as physical illness by healers like Kisir-Ashur.

You might say that Mesopotamian healers focused a great deal on communicating with the patient about the problems.

New insights in the doctor’s training

Kisir-Ashur recorded the treatments that he learned and used during and after his medical training.

He wrote his name, and often the purpose of the text. When you review the material chronologically, it reveals the progression of his training and preactice, says Arbøll.

Kisir-Ashur may have learnt his skills by practising on animals and progressed to treating babies when he was close to finishing his studies.

“It’s likely he did not treat human adults on his own before he was trained. This shows a relatively clear chronology in his training, where he takes on more and more responsibility,” says Arbøll.

Magic and science: hand in hand

The texts reveal that religious or magical rituals were a regular part of treatment.

The title of the text is often translated as “exorcist,” which is misleading as Kisir-Ashur was not working exclusively with the expulsion of spirits, says Arbøll.

“He does not work simply with religious rituals, but also with plant-based medical treatments. It is possible that he studied the effects of venom from scorpions and snakes on the human body and that he perhaps tried to draw conclusions based on his observations,” says Arbøll.

It was widely assumed that medical treatments for scorpion stings and snakebites had not been recorded before, since they were most often treated by magic.

“Kisir-Ashur observed patients with bites or stings. Perhaps he did this to find out what the toxins had done to the body and from that, try to understand the venom’s function,” says Arbøll.

Mesopotamian scholarship could have spread to Europe

The ancient Mesopotamians may have believed that some diseases and liquids were connected. This was partly based on the idea that human bile was toxic, says Arbøll.

“At this time, bile is considered similar to a venomous substance. It can regulate certain bodily processes and could be the cause or contribution to the cause of an illness. This idea is remeniscent of the important Greek physician, Hypocrites’ theory of humors, where the imbalance of four fluids in the body can be the cause of illness,” he says.

“However, the Mesopotamian conception of bile seems to differ from the Greek. Moreover, Hippocates lived some 200 years after Kisir-Ashur and the fall of the Assyrian Kingdom, so it is far from certain that the idea spread from Mesopotamia to the Greeks. But it would be interesting to investigate,” says Arbøll.

“If there are relationships between ancient Mesopotamian medical knowledge and Hippocratic medicine, which I think there are, we must show these connections in text, which is not easy,” writes Nils Heeßel, professor at the Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany, in an email.

“General assumptions on a single doctor’s academic focus can hardly be seen as a trace of later medical traditions,” he writes.

A snapshot of history

Kisir-Ashur’s clay tablets have been preserved for 2,700 years because the city of Ashur, together with Kisir-Ashur’s family library were burnt down in the year 614 BCE, during the dissolution of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

The library was preserved and first excavated by archaeologists at the beginning of the 20th century.

A large number of clay tablets were preserved well enough to be read, and the family library represents one of the most important collections of written sources from the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

People did not write theoretical works in Mesopotamia and the only way scientists can understand Assyrians’s thoughts and views of the world is by collecting various sources and combining letters and commentaries on medical treatments.

“Great Piece of Work”

The study provides a micro-history of Kisir-Ashur’s experiences in this specific town, at this particular time.

“It’s a snapshot of history that is difficult to generalise and it is possible that Kisir-Ashur worked with the material in a slightly different way than other practising healers. Kisir-Ashur copied and recorded mostly pre-existing treatments and you can see that he catalogues knowledge and collects it with a specific goal,” says Arbøll.

For Heeßel, this is the most exciting part of the thesis.

“It’s a great piece of work and for me this micro-history of the ancient Near East is the most interesting aspect of the thesis. It’s never been done before and I’m glad to see this concept used on our limited material in the region,” he writes.

Professor Fredrik Norland Hagen, who studies medical history at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, is similarly enthusiastic.

“The micro-historical perspective allows for a better understanding of how medicine in ancient Mesopotamia was practised and how medical knowledge was transmitted,” says Hagen, a professor in Egyptology at the Department of Cross Cultural and Regional Studies. He was not involved in the research.

“He has written a new chapter in Mesopotamian medical history. It is solid work,” says Hagen.

------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex