Bull fat, bats blood, and lizard poop were the drugs of choice in ancient Egypt

It took six months to describe and catalogue this A4 sized 3,500-year-old medical papyrus. See what Egyptologists have learnt so far.

“Bull fat, bat blood… donkey blood… what looks like the heart of a lizard. And a little pulverised pottery and a dash of honey.”

Egyptologist Sofie Schiødt traces her forefinger over the hieroglyphs as she reads aloud. We are in the papyrus reading room at the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

This bizarre recipe is not a mystical incantation but it is believed to be a recipe for a treatment against trichiasis--ingrown eyelashes.

The disease exists today just as it was in Ancient Egypt.

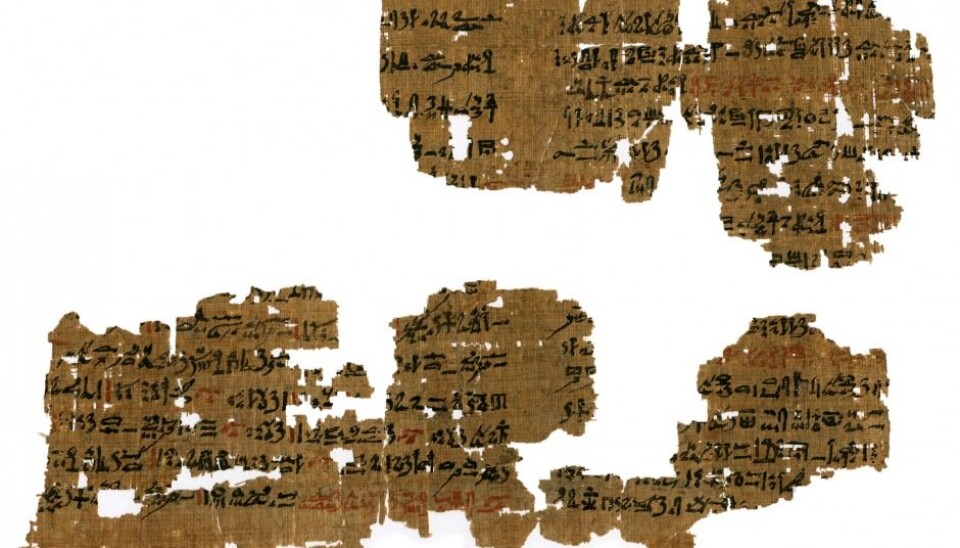

The papyrus is a 3,500-year-old medical record, which contains a recipe on one side and gynaecological text on the other.

“It’s something to do with whether someone is having a boy or a girl and birth prognoses. But I’ve mainly been working on the other side,” says Schiødt.

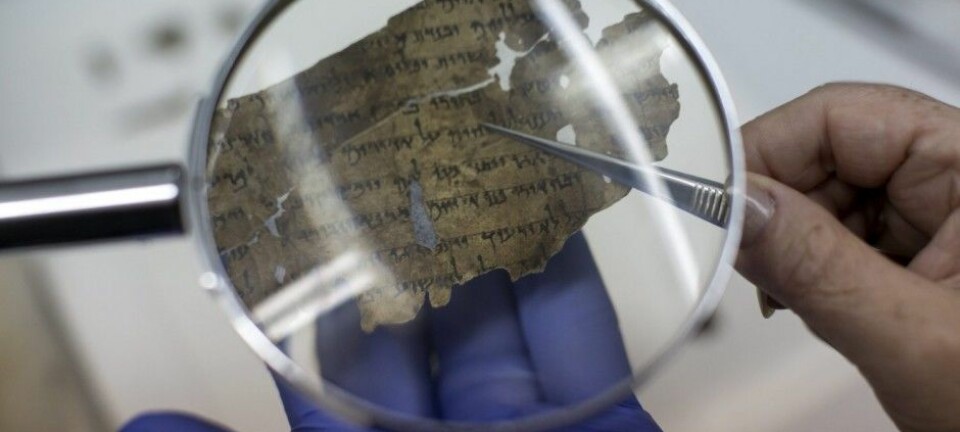

Read More: Archaeologists develop new technology to read ancient documents

Six months to study an A4 papyrus

It took Schiødt six months to read the entire papyrus, which consists of seven small fragments that, when combined, are about the size of an A4-sheet of paper.

“I think I could easily have used another year on this,” says Schiødt as she reads on: “lizard dung, beer, celery, and a woman’s milk who has given birth to a boy.”

The papyrus has been housed at the University of Copenhagen for 80 years, but Schiødt is the first Egyptologist to work with the 3,500-year-old prescription.

Read More: Danish Bronze Age glass beads traced to Egypt

Animal faces in papyrus

Small birds, ships, and snakes jump off the page as Schiødt reads the hieroglyphs from right to left.

“The red [texts] are recipes and mass quantities. The black texts are the ingredients and how to put them together,” she says.

“But it’s not always like this. You read in the direction that the animals face, which is reversed. So you have to read from left to right. Here there’s a cow, here a snake, and this is an owl. It corresponds to an m-sound,” says Schiødt.

Read More: Documents reveal 2,000-year-old Egyptian youth organization

Unclear what the prescription means

Schiødt received some unexpected help from another researcher in Germany, who had been working on a similar papyrus.

“It was a little bit of a ‘eureka’ moment. The ingredients were similar and it helped to put the bigger picture together,” says Schiødt, who now hopes to study the papyrus further as part of a Ph.D. project.

“Several treatment methods travel throughout the Arabian countries to Greece and on into Europe. Parts are weeded out along the way, the religious aspects especially disappear. But many of the ingredients, like lizards and bats appear again. I’d really like to map this transfer of knowledge,” she says.

“Many of the Egyptian texts go on to appear in Greek. How and why do people adapt the knowledge of one culture into another? What barriers apply? Linguistic or cultural barriers? There’s still much work to be done on the papyrus” says Schiødt.

---------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex