Archaeologists develop new technology to read ancient documents

Using X-rays and 3D-modelling, scientists have developed a new method to read ancient texts, which were until now considered unreadable.

About 1,300 years ago, a sorcerer arrived in the Muslim town of Jerash in Jordan.

Local Muslims saw that his magic was old and powerful and that he was desperately in need of their help.

We do not know why the wizard needed their help, but we do know this part of the story, thanks to an inscription of a thin silver plate that was rolled up and stored in an amulet.

Similar archaeological finds exist in museums around the world, recording ancient people's innermost feelings, fears, and dreams. But they are so fragile that no one has been able to unfold and read them. Until now.

A team of archaeologists led by professor Rubina Raja at Aarhus University, Denmark, have used CT scanning and advanced 3D-modelling to virtually 'unfold' the silver plate found in Jerash.

"It’s the first time that it’s ever been done for such a complex roll, and we can now use the same technique on other archaeological artefacts that have been folded or rolled up," says Raja.

The method now means that a whole raft of archaeological artefacts considered inaccessible, can now be read.

"There are some exciting new prospects for this [technique], because we can now access documents without destroying the source material," says archaeologist Søren Lund Sorensen at the Free University Berlin, who was not involved in the study.

The study is published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports.

Amulet discovered in house remains

The small amulet was found in 2014 during an excavation of Jerash, which has been inhabited by many different cultures from the Greeks to the Roman Empire, up until the early Islamic period from the mid-600s CE.

But around 749 CE, a devastating earthquake struck the town and it has remained untouched ever since.

Until 2014, when archaeologists excavated the remains of one of these collapsed houses and unearthed a treasure trove of glass bottles, coins, needles, ceramics, gems and gold jewellery, and the little silver scroll.

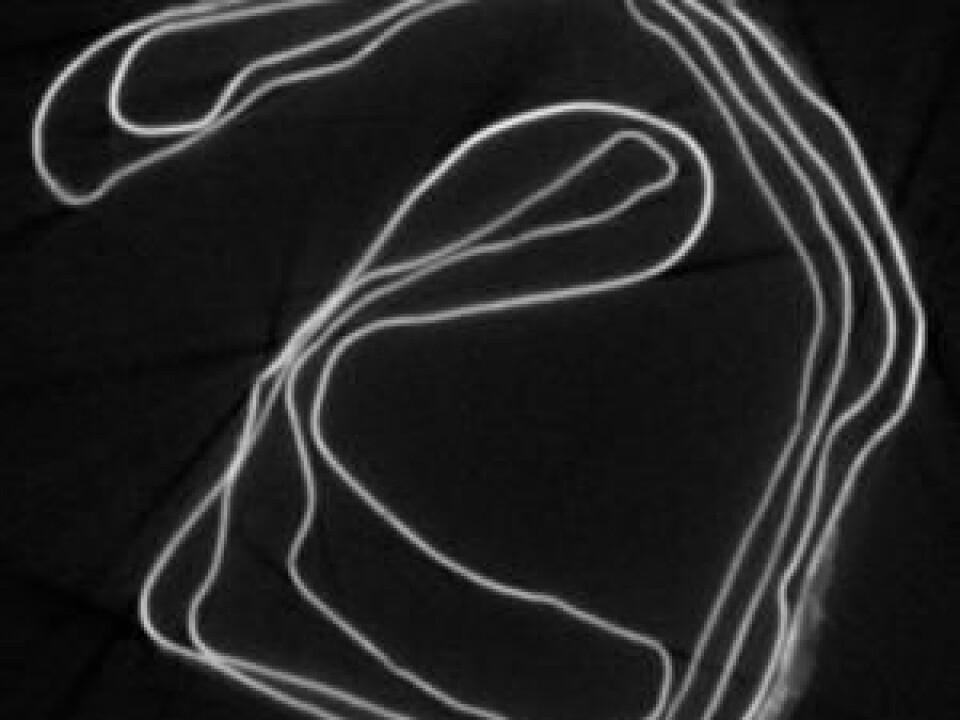

It is a small, metal cylinder, just five cm long. On the outside, it is cracked and corroded but inside they discovered the coiled and curly silver plate.

"The silver plate is only 0.01 cm thick. It’s very thinly beaten and it’s a magnificent specimen," says Raja.

Illuminates a fractured culture

After careful cleaning and restoration, they could clearly see one line of the script embossed on the back of the silver. But it was too delicate and fragile to try and unroll.

But Raja and colleagues wanted to know more about the little scroll: what was it, and what language was it inscribed in? Answering these questions could reveal the identity, religion, and ethnicity of those who lived in the house.

"It's exciting because this is a fractured part of history: between the late-antique and Arab invasion. Arabic arises in an area where the language was traditionally Greek and Aramaic," says Sorensen.

In other words, the scroll provides a unique insight into events occurring during this significant cultural shift.

CT scanning and 3D-modelling

In recent years, scientists have begun using new technology to access hidden texts.

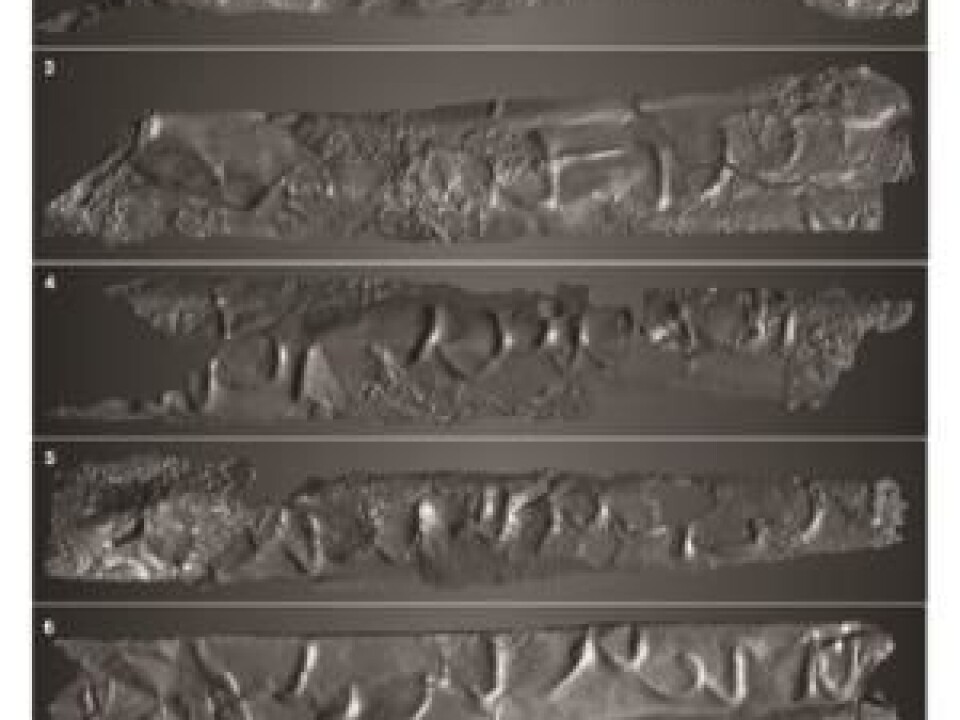

The technique here uses CT scanning to virtually unroll the scroll. But it required expert help.

After a long collaboration with engineers, one linguist was able to painstakingly identify faces and letters and slowly unroll the silver slip to reconstruct 17 lines of text made up of fine letters.

Secret ‘magical’ language

The first line consists of “magical” spells written in Greek characters. The remainder is comprised of Arab script that apparently no one is able to understand.

"We've sent it out to the world's leading philologists, and all came to the conclusion that they can’t read it, and that it must be pseudo-Arabic. They’re quite disappointed," said Raja.

"They often wrote in a secret ‘magical’ language that had no meaning, but you have to remember that very few people in antiquity could read and write, so the script in itself had some magical value," she says.

She imagines that a professional magician who could write in Semitic and Greek wrote the spell. One day he may have received a visit from an Arab who wanted an incantation, so the magician wrote it down, using the Arabic letters he knew, and the Arabian wizard then went home to hide the amulet.

"It was never meant to be read again, so it didn’t matter if it made sense,” says Raja.

But the mixture of Greek and Arabic letters is exciting in itself, because it shows a transition period, where Greek letters were used instead of inventing new characters.

"We always say that the Greco-Roman and Semitic traditions ended with the Arab conquest, but this is a really good example that they actually continued these practices, or that it was already part of the culture," says Raja.

-------------------

Read the Danish version of this article on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex