Soon computers can decipher your great grandmother’s scribbles

A program that can recognise old handwriting will soon be introduced in Denmark. Historians describe it as revolutionary and fantastic.

It is perhaps not every day that you need to read a letter from the 1800s. But if you are indeed curious enough to read your great grandmother’s diary, a computer program called Transkribus could be just what you need.

The program is already operating in a number of languages, including English and Norwegian to transcribe handwritten text, and now Danish historians are working hard to produce a Danish version.

“It could be revolutionary for the world of research if we can make this work optimally here. I think it’s really fantastic,” says Søren Bitsch Christensen, director of Aarhus City Archives and an urban historian. He is leading the initiative in Denmark, and presented his results during the 29th Congress of Nordic Historians in Aalborg, Denmark.

Read More: Researchers discover letters written to the Sun King’s wife

Important tool for historians

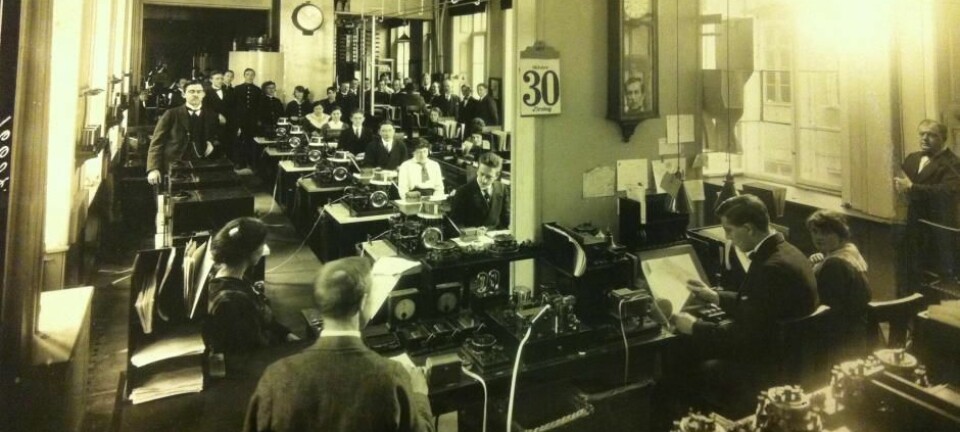

When the program is fully developed it will function as both a text recognition tool and as a database where you can search for old pieces of writing from Danish parish councils and town meetings.

And Christensen is not the only one who is excited about the new development.

“This could be very important for research, since this database of old handwriting can provide more results than those you might see yourself,” says Bo Poulsen, lecturer and historian at the Department for Culture and Global Studies at Aalborg University.

He spent 11 months transcribing old handwritten texts during his PhD studies.

“History is a research field, which is luckily framed by digitalisation and globalisation. It can potentially be very important for the research being conducted, because it enables you to search for Danish texts from anywhere in the world, which can lead to better research results,” says Poulsen.

“It could be interesting to search for which goods were shipped past Elsinore in the 1400s. At this time, the Danish king exacted tolls on all ship travel—the so-called Sound Dues—and here you would easily be able to see when southern fruits first came to Denmark and which types of fruit were most typically imported,” says Poulsen.

Read More: Dead Sea Scrolls still conceal many stories

Many people hours needed to get the project off the ground

Transkribus is based on an existing technology that recognises text.

As more text is added to the database, the programs database of comparison text grows so that it can recognise ever more text. In this way, the program acts as a search engine and a scribe of old written text so that it might be understood.

“The program is no cleverer than the material you feed it and it requires many thousands of examples before it can recognise a variety of writing,” says Christensen.

Volunteers across Denmark, who have the expertise to read the old texts, have been reading and adding old scripts into the database. The texts consist of protocols from the town and parish councils between 1840 and 1945.

The program has existed for around five years, but they are only just able to begin producing results.

“I have a single number from Transkribus in relation to the reliability of the program. It’s an analysis of a Norwegian diary from the 1800s. The program has analysed 3,500 words with a fail rate of eight per cent. In other words it has a success rate of 92 per cent, which is pretty good,” says Christensen.

Read More: Archaeologists develop new technology to read ancient documents

Time horizon is uncertain

The future funding of Transkribus is uncertain. It is currently supported by the EU and led by Innsbruck University in Austria. Christensen hopes that he can spark interest among stakeholders in Denmark who may be willing to support the project.

“We hope to raise more money, which can be used to employ people to drive the project so that we can create a larger database and introduce volunteers to use the program,” he says.

He adds that both funding and a lot of work are still required to make the program operational.

“I can’t yet say anything about how long it will take before the program is useful. It depends on how many volunteers write in,” says Christensen.

The tool is initially aimed at research institutions and researchers, but in time, he hopes that anyone will be able to use it.

Perhaps one day you will be able to transcribe your great grandmother’s old diary with a click of the mouse.

--------------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex