Red, white, and hot telephones: on hotlines and international diplomacy

The US and the Soviet Union had one. North and South Korea have just reopened theirs. Here’s a look at how hotlines have been used in modern diplomacy.

The third day of the new year in 2018 represented a symbolic thaw in the relations between North and South Korea: North Korea reopened the hotline between the two neighbouring countries.

The direct line of communication was disconnected in the previous two years after relations between the two countries worsened around the end of 2015 and beginning of 2016.

Hence, the material framework is now set to re-establish a diplomatic dialogue.

In physical terms, the hotline consists of a telephone line connecting the North and South in the border town of Panmunjom.

The telephone line has existed since 1971 and has periodically provided the setting for two routine calls each day between the two countries where South Korea called the North on odd dates and North Korea called the South on even dates. That is, until North Korea stopped taking their calls.

It remains to be seen whether reopening the connection is largely symbolic, and whether the dialogue will be of political importance or of a more down to earth nature. But history shows us that this type of hotline can serve many functions.

Read More: Friendships form countries’ foreign policy

MOLINK: the Cold War hotline

The best known hotline is that established between the US and the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

This connection was immortalised in the form of a red telephone when depicted in the film Doctor Strangelove in 1964.

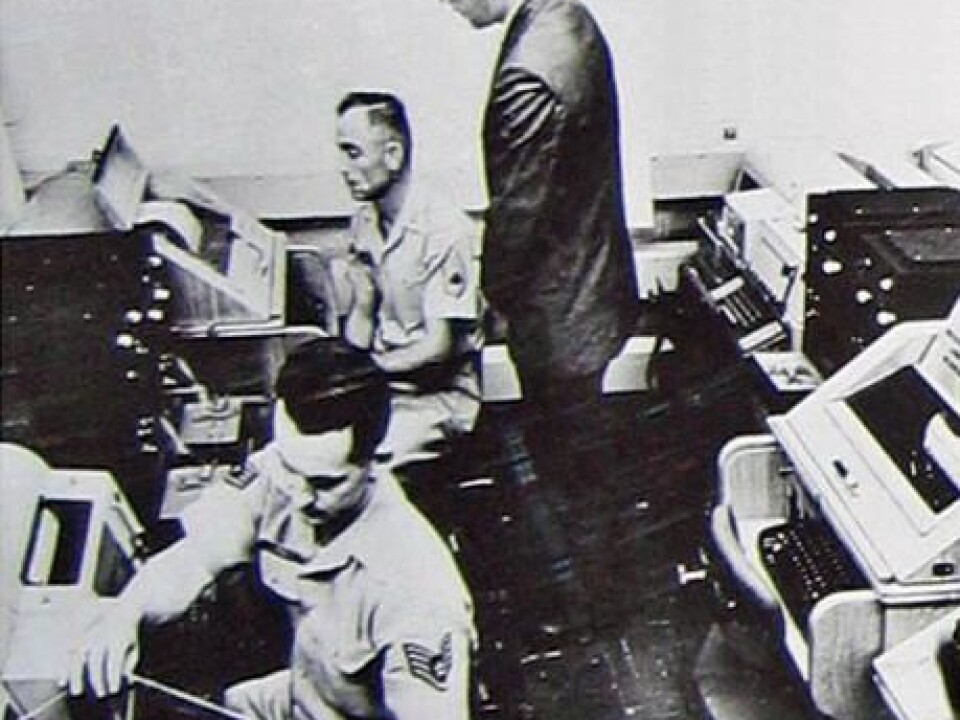

If fact, the direct line of communication between Washington and Moscow was not a telephone but a teleprinter. In the US, the hotline became known as The Washington-Moscow Emergency Connection Link or MOLINK.

The establishment of the hotline was some years in the making.

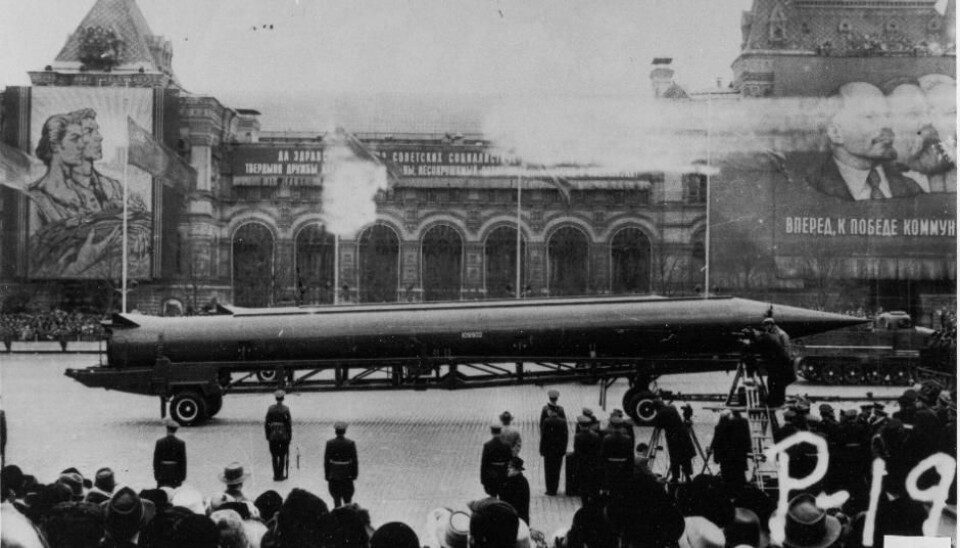

In 1954, the Soviet Union suggested establishing a form of security measure against a surprise attack. The fear was that nuclear war could break out due to a mistake or misunderstanding.

The idea was again discussed in 1959 when Nikita Khrushchev visited the US as the first Soviet leader.

According to a later US memo, Khrushchev expressed a wish to establish a ‘white telephone’ with a direct connection to the American President.

By the beginning of 1962, the Soviet Union suggested that the technical discussions on establishing such a connection should be initiated.

Read More: Denmark’s Cold War struggle for scientific control of Greenland

The hotline was ready to use after the Cuban Missile Crisis

However, it was the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 that sped up the process.

During these critical days in 1962, it took hours for the USA and the Soviet Union to exchange messages through existing diplomatic channels, because each message should be coded, decoded, translated, transmitted, and delivered.

The Cuban Missile Crisis underlined the need for effective and reliable communication channels in times of crisis.

Shortly after the crisis blew over, the US took the initiative to reopen the dialogue of how the super powers could reduce the risk of war caused by misunderstandings and communication failures.

The agreement fell into place in the spring of 1963 and the hotline was installed and ready to use by 30 August 1963.

The first incarnation of the hotline was a telegraph line routed via London, Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Helsinki.

The connection was supplemented with a radio circuit via Tangier and later modernised with satellite and fibre-optic connections.

So, the line was initially established for the purpose of crisis management. And it was with this end in view that the line was first used during the Six Days War in the Middle East in 1967.

However, it turned out that such a hotline had further potential.

Read More: Neutrality of government communications challenged by political PR-spin

Reassuring a nation

In certain diplomatic circles, the Washington-Moscow hotline was viewed with scepticism.

Diplomats worried that the hotline would be used for more routine political discussions over time and not just in crisis situations and thereby challenge the role of traditional diplomacy.

Yet, with a view to ‘public diplomacy’, a hotline had many advantages, first and foremost a psychological aspect.

For the public who had followed the Cuban Missile Crisis from the sideline and feared the outbreak of nuclear war, the existence of a hotline was a reassuring measure. While the talks on the establishment of the line were held in confidence, President Kennedy was well aware of the propaganda value of a hotline.

As he expressed in a speech in June 1963:

“[I]ncreased understanding will require increased contact and communication. One step in this direction is the proposed arrangement for a direct line between Moscow and Washington, to avoid on each side the dangerous delays, misunderstandings, and misreadings of the other's actions which might occur at a time of crisis.”

Accordingly, the hotline was presented by Kennedy as a phenomenon linked to détente – the relaxation in the east-west conflict that occurred in the years after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Read More: What this coin can tell us about ancient politics

Hotlines as an expression for political prestige

The Soviet Union also used the hotline for propaganda purposes. For instance in 1971, when the hotline was modernised.

While the US found it sufficient to make an amendment to the original 1963 agreement, the Soviet Union pushed for a new agreement to be signed into effect with a ceremony, providing a perfect photo opportunity.

Accordingly, hotlines can be used to signal good bilateral relations between countries. The symbolism, however, is defined according to each country’s individual perspective.

After the opening of the Washington-Moscow hotline, France and Britain also tried to link their capitals directly with Moscow.

In doing so they tried to reaffirm their role as great powers in international politics.

The British hotline was never realised during the Cold War, but a direct teleprinter link was established between the Kremlin and the Élysée Palace in Paris in 1966.

A few years later, Britain also tried to establish a hotline between London and Canberra, Australia, even though the risk of conflict between the two Commonwealth countries was minimal and they already enjoyed good communications. Here, the hotline was more a symbol of political prestige.

Read More: Internet sparks local political engagement

Softening relations between North and South Korea?

In the case of Korea, it is difficult to ignore the symbolic significance of the hotline, both when it comes to the closing of it and the recent reopening.

This is not least due to the very concept of a ‘hotline’ and the history associated with this type of communication.

North Korea stopped answering the phone in February 2016 because South Korea halted all activities in the joint industrial zone Kaseong as a protest against North Korea’s nuclear weapon tests.

Thus, the breakdown of communications was an antagonistic decision, a mark of reluctance and readiness for conflict, as part of a diplomatic duel in a period of rapidly escalating tensions.

The reopening of the line likewise signifies a willingness to start a dialogue and de-escalate conflict.

In practical terms, the north-south hotline is more of a direct communication link than a hotline per se, and its reopening most of all means that routine diplomatic messages can now be resumed. Yet, the reopening does signify a new and perhaps brighter chapter in relations between the two neighbours.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex

Scientific links

- 'The Origins, Use and Development of Hot Line Diplomacy'. Discussion Papers in Diplomacy, 2003.

- Article from BBC News: "North Korea reopens hotline to South to discuss Olympics" (2018)

- "Memorandum From Secretary of State Rusk to President Kennedy" (1963)

- "Memorandum From the Presidentʼs Press Secretary (Salinger) to President Kennedy" (1961-1963)

- "Memorandum of Understanding Between The United States of America and The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Regarding the Establishment of a Direct Communications Link" (1963)

- "Commencement Address at American University, June 10" (1963)

- Article from Korea Exposé: “Call Me Maybe: How N. and : Korea Actually Communicate (2017)