Can Greenlandic mud help feed the world?

Can nutrient-rich mud from Greenland transform poor tropical soils to produce more and higher quality food? This is what a new research project will study.

We all depend on food produced by farming. Our 10,000-year-old ways of hunting, fishing, and foraging for our primary source of nutrients have largely been a thing of the past, every since we began to cultivate wild plants and domesticate wild animals.

The first farmers used simple means but the full intellectual capacity of modern humans to identify which plants thrived best in which environmental conditions.

From their research, they constructed calendars and developed astronomical methods to track the seasons so they could sew and harvest at the correct time. They began to change nature, burn forests, direct water through channels, and change the landscape to make life as comfortable and productive as possible for their new crops.

Read More: Charcoal makes African soil more fertile and productive

From the earth we came and to the earth we will return

A fundamental understanding of agricultural societies is that all living things take nutrients from the soil and that these nutrients enter into cycles, whereby they are taken up by plants, eaten by animals, and are incorporated back into the soil each time an organism dies.

Plant growth in soil is an everyday miracle: Mineral nutrients are taken up and incorporated into tissue, inorganic becomes organic, stone becomes living, and life is created. For as long as we have understood this, we have also known that there are good soils and bad soils.

People who live on good soils are rich, and people who live on bad soils are poor. There’s nothing we can do about it. Or is there?

Andreas Neergaard og Minik Rosing talk about the possibilities of glacier flour at Science & Cocktails, Copenhagen. (Video: Science & Cocktails)

Nutrient poor soil in the tropics

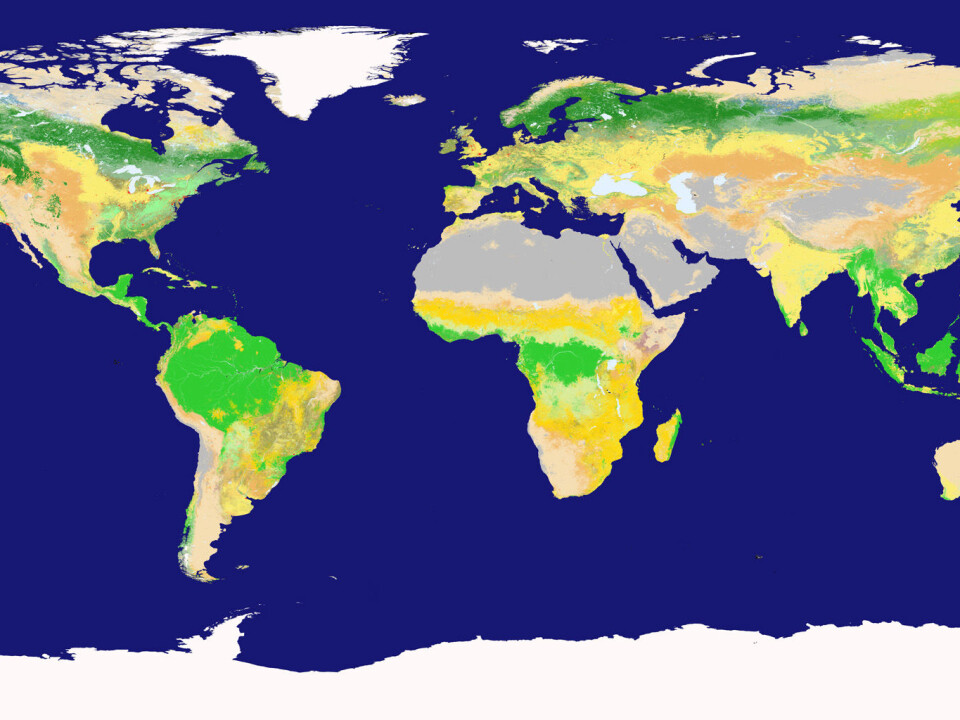

If we look at the distribution of wealth on Earth, a pattern quickly becomes apparent that conspicuously resembles the distribution of soils. A few countries produce almost all the crops that sustain us all, while many countries, despite being almost entirely dedicated to farming, cannot provide for their own populations.

The agricultural yield from a field of poor soil could be just one tenth of that in wealthier and more productive parts of the world. Why is that?

Poor, infertile soil is strongly over represented in the tropics and subtropics, despite the sun, warmth, and abundant rain.

It is, paradoxically, precisely this warmth and rain that makes these soils so poor in nutrients. The warm rainwater dissolves the minerals in the soil and carries the nutrients away, ultimately depositing them in the sea. Plants and large animals can thrive, so long as the soil is rich in nutrient-containing minerals. But soil fertility declines once the original minerals have all been consumed.

Many tropical soils are very old, meaning that they haven’t been exposed to geological renewal processes for millions of years, and have weathered after millions of years. When the primary minerals are dissolved, only the insoluble minerals remain, primarily aluminium oxide and iron oxide. Red tropical soils largely consist of these oxides.

Read More: Soil bacteria can clean your drinking water

The ice age created a belt of good soils

The most fertile soils in the world are found in Northern Europe, North America, and parts of Asia. They are concentrated in a belt that largely follows the ice front from the previous ice age. They are so productive because they are full of minerals that still contain lots of nutrients.

During the ice age, large ice caps and glaciers ploughed through the land and wiped away the decomposed and nutrient impoverished minerals. Instead, the ice deposited fresh soil from the crushed bedrock, rich in nutrients. And since these soils have been pulverised into dust by the ice, an enormous surface area is now exposed to plants, fungi, and bacteria, which can release the nutrients.

Read More: Arctic soils: a ticking climate time bomb

Greenland’s ice performs the same purpose as ice age glaciers

The only ice cap left in the northern hemisphere covers Greenland. Here, we can still study the processes that have created some of the most fertile soils in the world.

We can see how the ice pushes up moraines of material as it ploughs through the landscape, how it crushes the rocks underneath, and how the crushed material is transported out from underneath the glacier in the meltwater that pours out of the melting ice.

Colossal amounts of greasy, sticky, grey mud sits in front of Greenland’s glaciers. Millions of tons of new mud are deposited on top of the mud that already exists each and every day.

Read More: This approach not only binds CO2, but also improves the soil

Mud is not just mud

The mud of the Mekong River Delta or a muddy forest road in the Congo contain almost exclusively oxides of aluminium and iron—this is all that is left after the nutrients have been flushed out of the soil. The grey mud in Greenland, however, contains quartz, feldspar, and mica—the ingredients of Greenland’s granite bedrock.

The minerals are crushed to such a fine powder that it feels almost like soap between your fingers and you cannot feel the smallest grains or structure. The rocks are ground to incredibly fine flour, which we call, glacier flour.

The tiny grains gives this glacier flour an incredibly large surface area, which can react with water, roots, and microorganisms in the soil.

Read More: Scientists combat a tricky soil

From glacier flour in Greenland to bread in the tropics

So what if we could take this nutrient-rich glacier flour from the Arctic and transport it to the tropics?

In Greenland it is a nuisance and just sticks to your boots, but in the tropics the flour could be quickly activated and release its nutrients to the soil and plants.

Greenland will benefit economically with a new and sustainable industry, while people in the tropics will achieve a new level of wealth, better nutrition, and a brighter future. Can we do it? That is the question that we will now try to answer via research—a continuation of a 10,000-year-old tradition.

Read More: Is all soil more acidic than we thought?

On the way to a greener world

Right now, we are studying the composition of glacier flour—how it is produced, and how much there is.

We are testing how it influences plant growth and whether there could be problems associated with transporting it around the world or using it in practice. We are investigating whether we can accelerate the release of nutrients by using certain plants that release organic acids, or by combining it with soil of a high biological activity. We are also interested in how quickly and for how long the glacier flour can release nutrients.

Our ongoing results from trials in herb pots in Copenhagen, Denmark, are encouraging and show that our hypotheses are correct. And we have just started a series of trials in Brazil to see what effect it might have on tropical fields.

We still don’t have enough detailed studies to say whether large scale transport of glacier flour from Greenland to the tropics will be ecologically and economically sustainable, but we haven’t seen anything yet to discourage us.

We expect to have these answers within a few years so that together, Greenland and the tropics can address two of the worlds biggest and related challenges:

- How do we feed a growing population?

- How do we avoid depleting arable soils by intensive farming?

We hope that Greenland’s need for new industry and income opportunities can meet with the tropical countries’ need for more effective agriculture, and that solving these two problems can leave a better, greener world for us all.

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex