Science communication: 'you're allowed to spice things up'

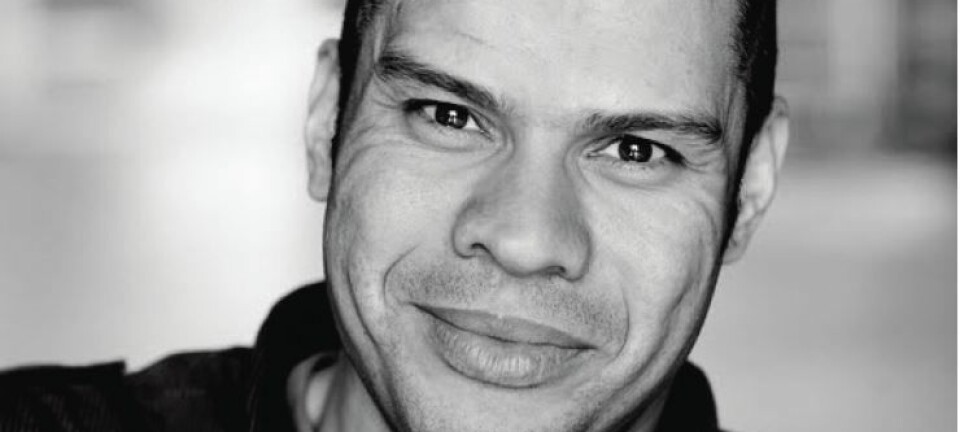

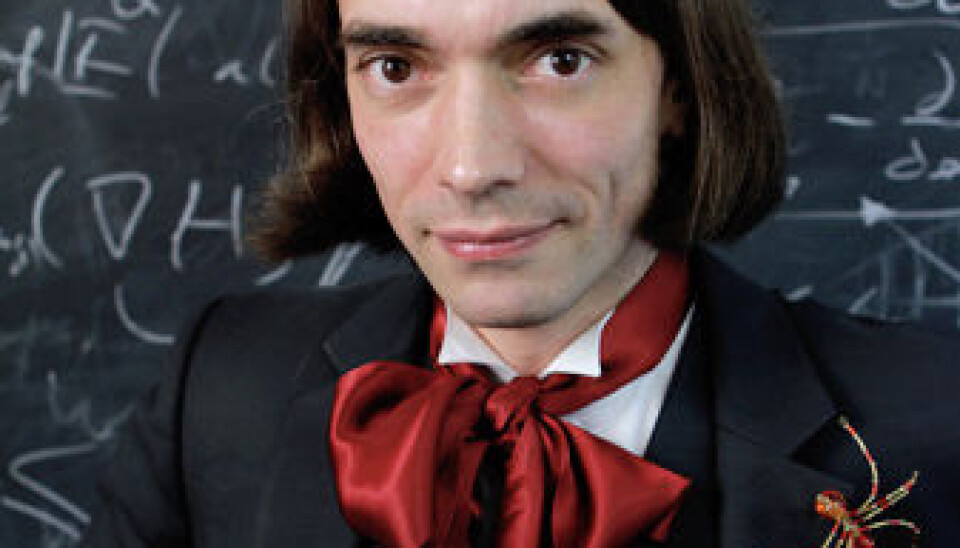

How do you make the abstract world of mathematics fascinating to a broad audience? A Q&A with award-winning mathematician Cédric Villani.

Mathematics may well be one of the most abstract sciences – related to both philosophy and theoretical physics and a challenge to even define as a science. However, this does not prevent Cédric Villani, who received the prestigious Fields Medal in 2010, from sharing his knowledge of the mysterious world of mathematics with a wide audience -- including a long series of TED talks.

Villani is a professor at the University of Lyon and the director of the Institut Henri Poincaré in Paris. We got a chance to have a one-on-one with him.

ScienceNordic: How did you start communicating your research to the public?

Villani: “My first experience in this respect was when I was hired as a professor in Lyon; I had an interview for inclusion in a semi-technical magazine that reported results in an academic context. So the audience consisted of academics, but not necessarily fellow mathematicians. The interview was conducted by a professional journalist, but ended up in disaster. The journalist understood so little – without daring to tell me – that he refused to write up the article, and it had to be done another time, this time by an academic. In retrospect, it is clear that I was not prepared for this kind of exercise at the time.

It all changed when I attended a two-day training seminar about communication with the media. The person who ran the session gave us some explanations about the goal, psychology and social status of an interviewer, about the expectations of the public, and some tips about possible ways to present stuff in a way that would be striking, relevant and suited to the audience. Our group performed some mind-opening exercises. This piece of training has been one of the most important in all of my professional activities.

Later I did some public lectures, and it exploded after the Fields Medal. In the past few years, I have given hundreds of public lectures – for students of any age, political gatherings, professional gatherings, companies etc. Some of them were also intended for the general public, of course.”

When you communicate, do you think about how your research colleagues will react to what you’re saying?

“It is important to pretty much forget about your research colleagues when you are giving a lecture; in particular, do not worry about saying things that are not perfectly accurate, as long as the public understands the main ideas.

That being said, if the talk is well prepared, research colleagues will also enjoy it. Indeed, a public lecture is not so much about simplifying things as it is about presenting them differently. Illustrations, cultural or historical remarks, differing perspectives and the like will contribute to making it different.

It is also important to seize opportunities to relate to your research colleagues when they are in the audience, by mentioning that X is an expert on this, or telling an anecdote involving a discussion with Y, or saying that Z knows more about this subject than you, or something along those lines. This is a way to bring them into the process, but also to instil the idea of the importance of the community you are addressing in your lecture, and to put more life to your scientific field.”

How do you know when to compromise on precision to spice up your communication and when to be strictly scientific?

“Simple: you are always allowed to spice things up. For a scientist, trained to have rigor as a constant concern, it is almost impossible to be too spicy; especially for a mathematician. As long as you yourself find it interesting and in good taste, you can go for it."

What are your best communication tips for other scientists?

“My most important piece of advice for fellow scientists is to get professional training. It can be just one day of practice, but this can have an enormous impact on the way you present things.

My second piece of advice is, during a public lecture, to be very aware of the reactions of the audience, and to note which of the tricks worked and which did not. Then go back to your lecture and improve it, or think of a new trick.

My third piece of advice: whichever subject you are talking about, you absolutely have to make your audience laugh several times during the talk."

-------------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dan Vinther