Dead man’s genome reconstructed using DNA from living relatives

Extensive detective work pays off.

“It sounds just like Jurassic Park.”

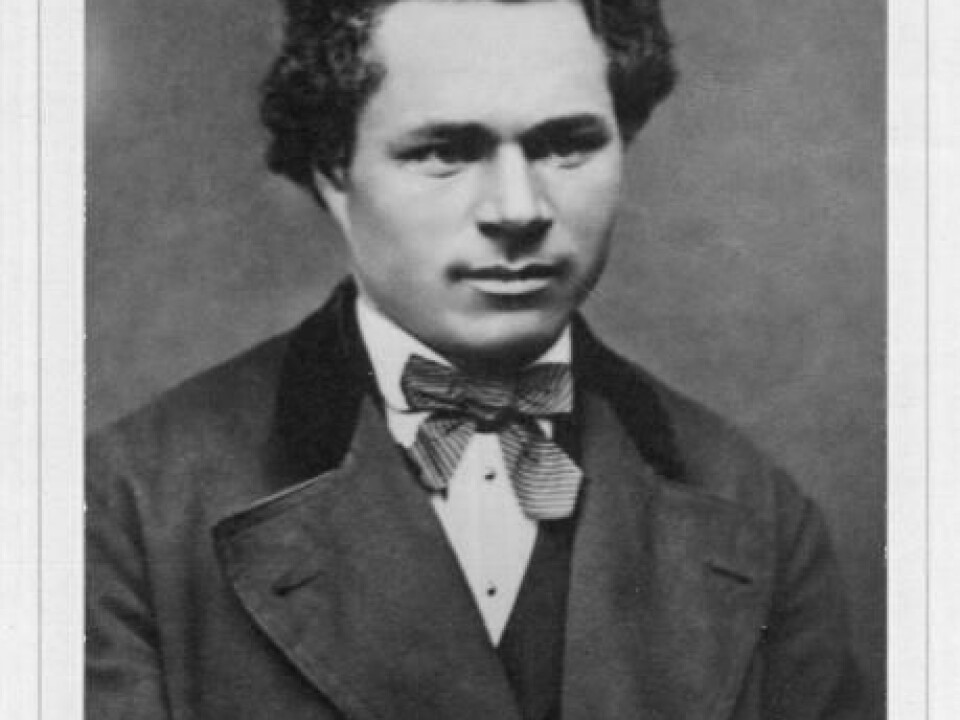

This was how Professor Karsten Kristiansen from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, reacted when he heard that scientists in Iceland have reconstructed the genome of a Hans Jonatan.

Born into slavery in the West Indies 236 years ago, Jonatan moved to Denmark as a child together with his family and their Danish owners.

His physical remains have long since disappeared. Unable to study Jonatan’s DNA directly, scientists reconstructed his genome using DNA from his living descendants. It is the first time that a research team has shown that this is possible.

The results are published in the journal Nature Genetics.

Hans Jonatan: The Icelandic symbol of freedom

Jonatan, who had a Danish father and an African mother, left his life as a slave behind when he fled from Denmark to Iceland in 1802. He died there, a free man, aged 43 in 1827.

Today, Icelanders regard him as a symbol of freedom.

Professor Mikkel Heide Schierup from the Department of Biology at Aarhus University is fascinated by the results.

“My immediate reaction was that this was great. It’s a fascinating piece of work,” says Schierup. He was not involved in the research but praises the high quality data used.

Read More: Patients in Pakistan donate DNA to European research but are unaware of the goals

Possible due to Iceland’s extensive national genetic database

In Iceland, Jonatan met his wife, Katrin, and they had two children. This was the start of a genealogy that today counts around 1,000 descendants.

The Icelandic scientists used DNA from 182 of them to reconstruct 38 per cent of the genetic material that Jonatan received from his African mother.

The scientists behind the research were helped by the fact that Jonatan was the first African to set foot in Iceland and the fact that the country keeps an extensive national genetics database.

Read More: How to track down your ancestry with DNA

Data fits models perfectly

Reconstructing Jonatan’s genome was a piece of detective work, says lead-author Kári Stefánsson, director of the Icelandic Genetic Research Centre deCODE.

“I’m not surprised by what we have discovered from this work, but I’m very satisfied with it. We’ve been working on it for some time,” he says.

Jonatan’s genome was a good target for this kind of reconstruction, says Schierup.

“Hans Jonatan is only found in genetic material today because we know that for a long time, he was the only one with an African background living in Iceland, and because we know that he had descendants. We have theoretical models for how genes spread from generation to generation, and 38 per cent are precisely what you might expect to find over a couple of hundred years,” says Schierup.

So while these results are not surprising, it is a good illustration that the theory matches practice, he says.

Read More: DNA confirms Australian Aboriginals are the oldest civilisation still around on Earth

Unique opportunities in Iceland

According to Stefánsson there is, in principle, nothing that prevents us from doing the same thing for other people.

The number of descendants you need simply depends on when the person died.

“To perform a similar piece of work, you will need roughly the same number of descendants. It is 200 years since Hans Jonatan died, so in many ways it’s very timely for us,” says Stefánsson.

Schierup agrees, but adds that Iceland has “fantastic resources” because the scientists already have so much genetic information on the population.

“This means that they have opportunities that you don’t get in other places where it would be more difficult to do this work. But it’s only a matter of time before the entire world’s genome has been mapped and now the methods are ready,” he says.

Read More: Scientists want to collect your DNA when you die

Hans Jonatan: The first African in Iceland

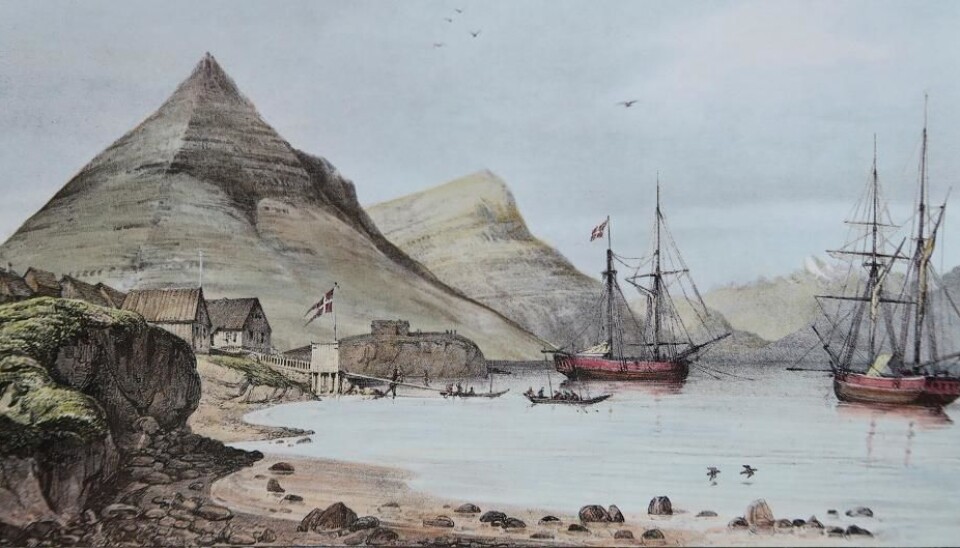

Stefánsson actually has a personal reason to dig into Jonatan’s history. He grew up in the town of Djupivogur, where Jonatan arrived in 1802. He was received with open arms despite the fact that the population had never seen a black man before.

Stefánsson’s father described the scene in his biography, published in 1986.

“The scientific interest is huge because we show that you can used genetics to trace history, but it’s also a beautiful story. If my father was alive today, he would be very happy,” says Stefánsson.

--------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex