Computer model mimics mechanism behind pressure ulcers

OPINION: Danish scientists are trying to uncover why pressure ulcers occur. This is done with computer models and lab tests in which cells are exposed to mechanical stress.

An extremely unpleasant side effect of being dependent on a wheelchair is that you risk developing pressure ulcers, also known as ‘bedsores'.

‘Pressure ulcers’ is a general term for the type of ulcer that is also very common in people who have been bedridden over prolonged periods due to illness.

To people who already suffer this unfortunate fate, pressure ulcers can quite rightly be regarded as adding insult to injury – and furthermore, the cost of treating pressure ulcers adds extra pressure on health budgets.

All things considered, there are good reasons for doing something to solve these problems. One could say that this is the serious background for my PhD project about pressure ulcers in wheelchair users, which I carried out at the Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering at Aalborg University, Denmark.

Pressure ulcers and ground reaction forces

Statistics show that almost all wheelchair users will at some point in their lives experience pressure uclers, which for obvious reasons typically arise on their buttocks – particularly below the sit bones or on the tailbone.

Generally speaking, pressure ulcers arise – as the term suggests – as a result of mechanical stress on a small part of the body.

However, other than this trivial observation, not a lot of detailed knowledge exists about what mechanisms are at play when the tissue gradually breaks down.

Welfare technological solutions to the problems with pressure ulcers therefore require a greater understanding of how the tissue responds to mechanical stress.

In my study, I analysed the ground reaction forces exerted between a chair and a person sitting on it, and how these reaction forces deform the tissue under the buttocks.

The analysis combines two computer models

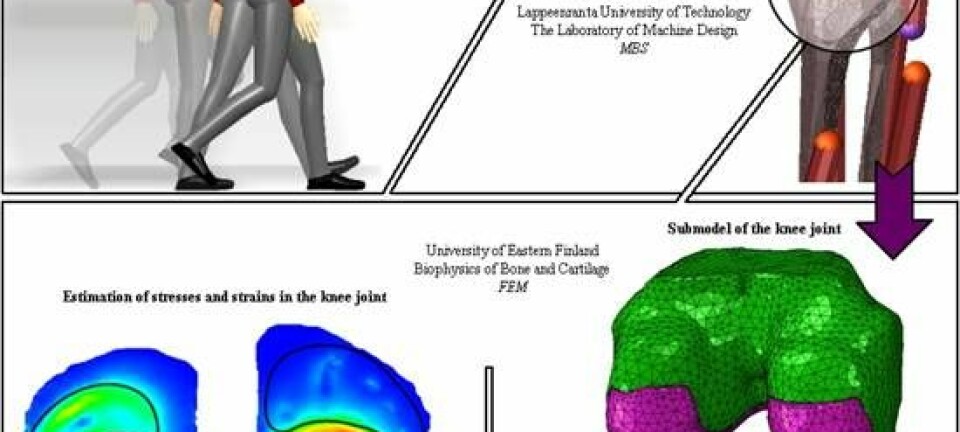

The analysis was carried out by combining two computer models – one that calculates the ground reaction forces between the chair and the person, and one that calculates the deformation based on the ground reaction forces.

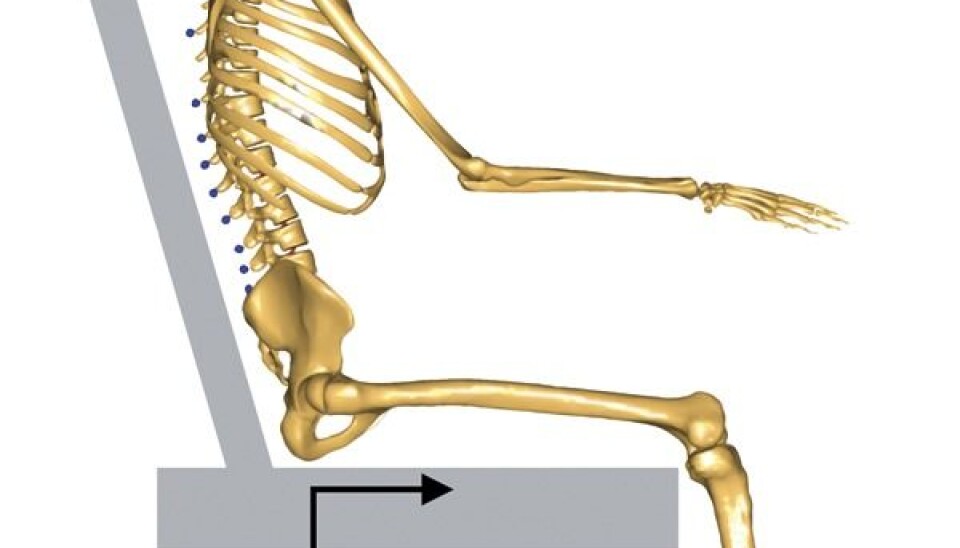

The first part of this analysis was done using a computer model developed with ‘AnyBody Modeling System’ software, which is a modelling system for creating computer models of humans interacting with an environment such as a chair, a bike, a car seat or the like.

When we place our sitting AnyBody model in a virtual chair, we can then calculate the ground reaction forces between the chair and the person, based on how the model is sitting.

These forces are used as input in another model of a seated human body, developed by the German company Wölfel, which specialises in car seat designs.

This so-called ‘Finite Element model’ (FE-model) can calculate the state of deformation in the tissue under the buttocks – tissue that is at risk of being damaged.

Calculating the state of deformation in cells

The state of deformation calculated from the FE model is not of much value on its own as long as we don’t know how the tissue under the buttocks breaks down.

The scientific literature suggests that the soft tissue, popularly speaking, does not tolerate being twisted to the same degree that it tolerates being compressed.

It is still unclear to what degree the tissue tolerates different forms of deformation.

We are therefore now, as the next step in our study, carrying out laboratory experiments in which we look at what types of loads the cells can withstand.

Cells are manipulated mechanically

The experiment consists of growing cells and inflicting them with mechanical deformations that can be compared with the deformations that are calculated in the FE model.

The challenge with this is that it is difficult to maintain cells at the same time as stimulating them mechanically with a controlled deformation state.

The first thing to do is to get immature cells to form in the same way as regular muscle cells – i.e. cells with the characteristic that the individual cells merge, so to speak, into elongated fibres with many nuclei. We get our immature cells from a commercially available cell system, which is designed to expose growing cells to pressure.

We have developed a method in which we stimulate these cells mechanically.

This causes them to align and structure themselves into parallel lines just like in a muscle when they mature from an immature stage to an early type of muscle fibre.

We are currently working on maintaining the ‘muscle fibre’ and exposing it to mechanical stimuli that correspond to a person sitting on his or her backside.

If this brings us nearer a fundamental understanding of why a pressure ulcer starts under the buttocks, it may enable us to develop guidelines and products that can minimise the risk of developing pressure ulcers.

-------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther

Scientific links

- "Missing Links in Pressure Ulcer Research - An Interdisciplinary Overview", Journal of Applied Physiology, DOI: 10.1152

- "The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK", Age and Ageing, DOI: 10.1093