Well-preserved dinosaur was witness to a scary past

The dinosaur is believed to be 110 million years old and could be a new species.

“Spectacular,” “scary,” and “surprising.”

These are some of the words used by scientists to describe the 110-million-year-old dinosaur that has been discovered in Canada.

The 5.5 metre long dinosaur is called Borealopelta markmitchelli, and it is a previously unknown species, shows a new study.

“The special thing about this dinosaur is that it’s big and armoured, but we can see that it was prey. It’s a witness to a world with insanely scary predators. Much scarier than predators today,” says co-author Jakob Vinther, a senior scientist at the University of Bristol, UK.

Best-preserved dinosaur discovered in decades

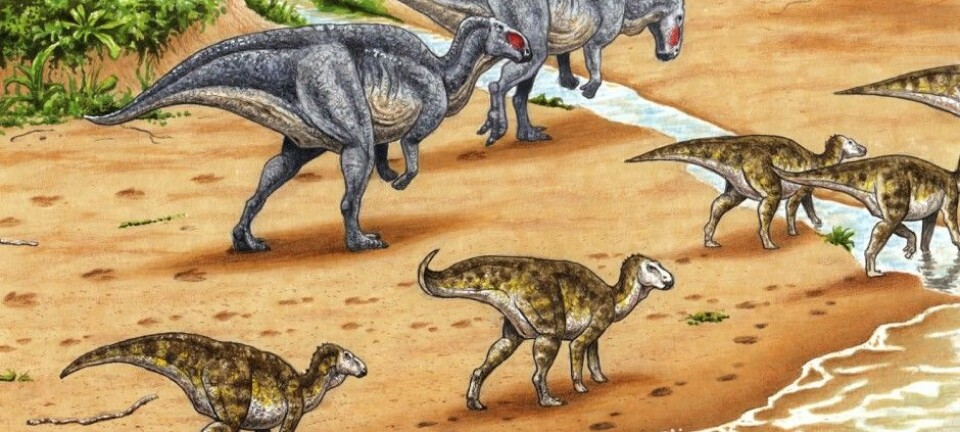

The newly discovered dinosaur was a vegetarian and belonged to the dinosaur family nodosaur. It was fully armoured with horns down its back, and the scientists estimate that when alive it would have weighed around 1,300 kilograms.

According to dinosaur expert Stephen Brusatte, who was not involved in the study, Borealopelta markmitchelli provides a “fantastic opportunity” to study the life of dinosaurs.

“The new dinosaur is one of the most spectacular, beautifully preserved skeletons discovered in the past few decades. Almost all of the bones are there, together with some of the soft tissue that covered the bones while the dinosaur was alive. It’s extremely rare that a dinosaur is preserved in this way,” says Brusatte, who studies dinosaurs at the University of Edinburgh, UK.

The dinosaur bones were recently on display at the Royal Tyrell Museum in Alberta, Canada, where their exceptional preservation received much attention.

Colour is preserved

In the new study, scientists found preserved pigments–grains of colour—in the dinosaur’s skin and armour.

“Our chemical analyses show that it was a red-brown colour,” says Vinther, who is one of the world’s leading experts in identifying colour pigments in fossil animals.

“We can see that it was lighter underneath than on top. This is called countershading, and it’s a form of camouflage that we see in many present day animal species. Take for example, a deer, squirrel, or a penguin. They all have a lighter underbelly because it makes it harder for predators to spot them,” he says.

“It’s very well known that many animals have developed counter shading, because it’s an evolutionary advantage for them. When animals are harder to see, there’s a smaller chance that they are eaten, and thus they can carry their genes forward,” says Vinther.

Concrete evidence for ferocious predators

The countershading on the newly discovered dinosaur is the most surprising aspect, as it shows that it was a prey, says Brusatte.

“It’s unbelievable because this dinosaur weighed over a ton and we don’t see such large animals with counter shading in the current animal kingdom. It tells us that the carnivorous dinosaurs that ate this new dinosaur, were probably very ferocious,” he says.

Another study recently concluded that the most famous predator—Tyrannosaurus rex—was perhaps a bit of a slow coach and the fastest it could run was 20 kilometres an hour. Other scientists have even estimated that T. rex could only run 4.5 kilometres an hour, and that people could therefore easily have outrun the large predator.

“Even though Tyrannosaurus rex is popularly known to be extremely dangerous, there’s actually a lot of debate among scientists about how scary they actually were. Some think that they were so slow that they were perhaps just scavengers,” says Vinther.

“Our find points in the other direction, because our dinosaur is camouflaged, so we have some of the most concrete evidence that in all likelihood there were predators equipped to fight such large, heavily armoured herbivores,” he says.

--------------------------

Read more in the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex