Scientists discover flower seeds from the dinosaur era

The seeds are believed to be those of the very first flowering plants on Earth, making them 110 to 125 million years old.

Scientists have discovered the earliest known seeds of flowering plants. The seeds are estimated to be between 110 and 125 million years old.

They are so exceptionally well-preserved that scientists can see their internal cell structure, which provide clues as to how the plants lived in an ancient world ruled by dinosaurs.

Some of the prehistoric flowering plants were small--not much different from the herbs and shrubs that we recognise today, except they were not as common.

"These plants were less advanced than most of today's flowering plants. They were not so opportunistic [and] it took them a long time to germinate and establish themselves,” says lead author Else Marie Friis, professor of plant palaeontology at Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm.

“It’s quite unique to find such well-preserved seeds, which gives us a great opportunity to study how the planet's very first flowering plants appeared and evolved," she says.

The new discovery is published in the scientific journal Nature.

Important piece of the evolution puzzle

Associate Professor Gitte Pedersen, studies ancient plants at the Natural History Museum at University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

She was not involved in the new study, but she has read it and thinks it is a fine example of how fossils give important insights into plant biology.

"It gives us the key pieces [of the puzzle] to understand how evolution has proceeded. Without that understanding, it’s difficult to explain the changes we see today, and it’s quite impossible to try to predict what will happen in the future, "says Pedersen.

Studied the seeds of 75 plant species

In the new study, the scientists collected samples of sediment from lakes and streams in Portugal and the US, which date back to the Cretaceous period between 110 and 125 million years ago.

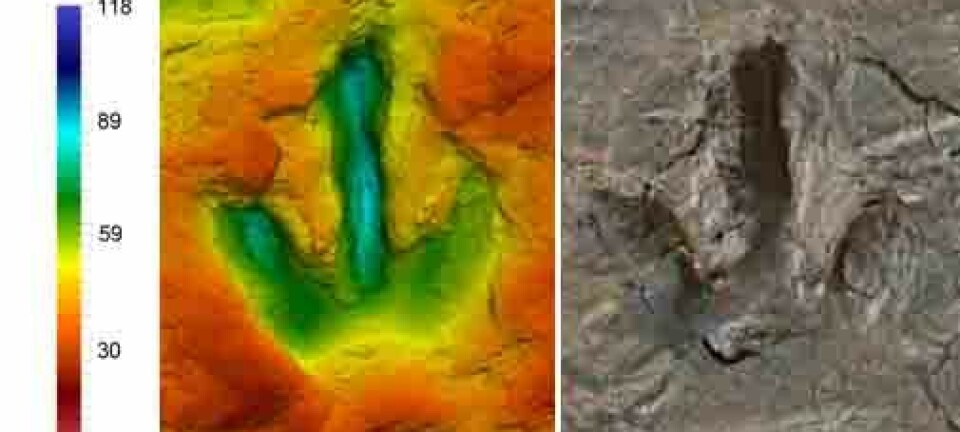

Within these prehistoric sediments, they found 250 seeds from 75 different species of flowering plant, which they examined by Synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy--a particularly advanced microscope that creates detailed 3D images of the seeds internal structure.

"In about 50 of the seeds, the internal structures are exceptionally well preserved,” says co-author Kaj Raunsgaard Pedersen from the Department of Geoscience at Aarhus University, Denmark.

“We can see the various structures that look like cell nuclei, proteins, and lipids. From this we can learn something about how they germinated, and what was needed for the plants to start to grow," he says.

Flowers were not opportunistic

By studying individual plants, scientists could infer a lot about plant life.

For example, they determined the slow germination times by comparing the relative proportion of the germ to seed.

A small germ to seed ratio indicates that the first stages of growth occur inside the seed itself, using nutrition from the seed’s tissue, and require favourable conditions to germinate and develop.

But if the ratio of germ to seed is high, then the seed germinates much more quickly.

"These earliest flowering plants didn’t establish themselves very easily and they didn’t grow to be very tall. It's funny when you consider that perhaps 90 per cent of all vegetation today are descended from these earlier flowering plants," says Friis.

Solves one of Darwin’s mysteries

The new research also casts light on one of the problems that Charles Darwin struggled with.

Darwin couldn’t explain the sudden explosion in the abundance of flowering plants 100 million years ago, as it was recorded in the fossil record in Darwin’s time. It seemed to be in stark contrast to his own theory of gradual evolution.

Since then, many other fossils have been discovered; some up to 25 million years older than those available to Darwin.

But the new research shows just what these plants looked like, how common they were, and why their seeds were hard to find.

"The flowering plants were much more diverse and fewer in number than was previously believed. Their seeds were also very small, which is why they have been so hard to find," says Friis.

--------------------

Read the Danish version of this story on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Catherine Jex