Tree-jumping taught dinosaurs to fly

The earliest dino-birds had wings that could only be used for passive flight between treetops, new fossil analysis reveals.

Today’s gulls and crows have a common dinosaur ancestor. It had special, primitive wings which it lashed out to help it jump from tree to tree.

A new study of 155-million-year-old fossils of birds and dinosaurs reveals that the wings on the ancestors of today’s birds had a different appearance than previously thought.

The new discovery supports an otherwise underrated theory of how birds learned to fly.

“Our studies of the feathers on the earliest wings show that dinosaurs learned to fly by climbing trees and jumping from one tree to another,” says co-author Jakob Vinther, a Danish lecturer at the departments of Biology and Earth Sciences at Bristol University, UK.

"The early purpose of evolving feathers was to increase the surface area of the dinosaur so it could hover over longer distances. Much later on in the evolution they could go even further by flapping their front limbs, and eventually they could fly,” he says.

See related story: Sex made birds spread their wings

Fossils from the bird’s infancy

The international research team has made the discovery by examining fossils from two of the bird’s ancestors, which date back to the Jurassic period.

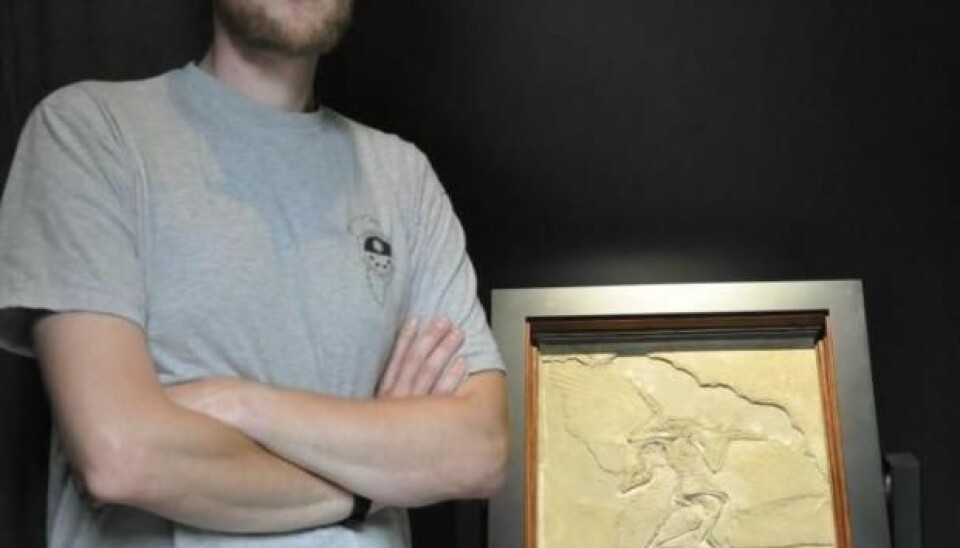

- Archaeopteryx – sometimes referred to by its German name Urvogel (‘original bird’ or ‘first bird’). The particular fossil in question was the so-called Berlin fossil, which was discovered by a German quarry worker in the mid-1870s.

- Anchiornis (‘near bird’) – a genus of small, feathered, troodontid dinosaurs. Discovered as recently as in 2009, this genus was the first dinosaur to have its original colour richness reconstructed.

Our studies of the feathers on the earliest wings show that dinosaurs learned to fly by climbing trees and jumping from one tree to another.

“They both date from the period when the dinosaurs were evolving into early avian forms, whose descendants would evolve into the birds we see today,” says Vinther.

Wings for hovering flight only

The fossils were so well preserved that the researchers could clearly see the markings from the animal feathers in the hard rock. Suddenly they noticed a hitherto overlooked feature of the Archaeopteryx fossil wing.

“Modern birds and the Archaeopteryx both have so-called ‘flight feathers’ on their wings – that’s the feathers on the tip of the wing,” he says.

“But we noticed a difference in the feathers located on top of the flight feathers. Modern birds have lots of short feathers, but the ‘original bird’ had several layers of long feathers, which are up to 90 percent of the size of the flight feathers.”

Modern birds have lots of short feathers, but the ‘original bird’ had several layers of long feathers, which are up to 90 percent of the size of the flight feathers.

This may sound insignificant to most of us, but Vinther and his colleague Nicholas Longrich knew that a wing like that could under no circumstances be used for any flight that resembles the flight of modern birds.

See related story: Colour secrets revealed in fossilised fish-eye

The many long feathers prevented the Archaeopteryx from flapping their wings. Their wings could at best be used as a soaring mechanism.

Modern birds, on the other hand, have a special wing design, which allows air to flow freely between the wing quills on the upstroke. On the downstroke, the feathers contract to form a tight membrane, so that no air can flow through. This is how today’s birds can gain height with the downstroke without losing it on the upstroke.

A part of the evolution of the bird wing

This type of wing was probably the standard among the bird’s primitive ancestors. In other words, this type of wing is part of the evolution of the bird-wing.

From his previous studies of the small dinosaur Anchiornis, Vinther knew that it had a wing that resembled that on the Archaeopteryx with its long contour feathers.

“We found that very interesting,” he says. “The two animals are located at two completely different points on the genealogical chart for birds. The Archaeopteryx is more closely related to birds than Anchiornis is,” says the researcher.

“This means that this type of wing was probably the standard among the bird’s primitive ancestors. In other words, this type of wing is part of the evolution of the bird-wing.”

See related story: The mother of all birds had black wings

Birds didn’t use the ground as a runway

This discovery marks a break with the predominant hypothesis about how dinosaurs evolved into birds.

In the US, there’s a distinguished group of palaeontologists who believe that the dinosaurs didn’t climb up the trees at all.

”Instead, they argue, they ran around on the fields, where they learned to flap their front limbs. Eventually they developed the ability to take off, and then they learned to fly with the wings they had evolved,” says Vinther.

“But our discovery challenges that hypothesis.”

Find in China supports climbing hypothesis

The new perspective on the bird-ancestors’ wings – in conjunction with other fossils – points clearly towards the tree-climbing hypothesis.

“In China, for instance, a so-called Microraptor has been found. It has four wings – it has feathers on the arms as well as on the legs,” he says.

“But I’m 100 percent certain that it did not use its hind legs for flapping, because it didn’t have the muscles required for that. This fact suggests that it used its feathers for passive flight and that these forms evolved feathers to create a large surface area.”

He says that even though it’s hard to convince people with a different persuasion, the new discovery could help revise the popular explanations of how dinosaurs evolved into birds.

The article ’Primitive Wing Feather Arrangement in Archaeopteryx lithographica and Anchiornis huxleyi’ has just been published in the journal Current Biology.

-----------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther