Schizophrenia and severe depression share biological process defect

Some of the most severe mental illnesses share the same defective coding of biological processes down to the cellular level.

Some days there are hundreds, other days there are just a few. But they're always there, the men in black.

They've been following Kirstine Birkelund for as long as she can remember.

"They don't do anything, they just keep an eye on me. Sometimes they get other people to plant microchips on me. Then I have to rub them off on something, because I mustn't touch them," she explains.

To Birkelund, the men are as real as both the doctor who subscribes her antipsychotic medication and the white walls at the psychiatric ward at Copenhagen's Bispebjerg Hospital where she is frequently admitted.

Although she has no idea why these dark fellows appear, she does know what they want: to frame her for a murder she didn't commit.

The cause of the men in black may lie deep within the cells that make up Birkelund. A team of international scientists have discovered that serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression may be linked to disruptions of the same biological processes in the body that are controlled by very specific genetic variations.

These results were recently published in Nature Neuroscience.

Genetic flaws explain flawed processes

The new study builds on a large genetic mapping project that began in 2009.

Since then, a number of genetic studies have examined samples from 60,000 mentally ill people.

From this research, scientists have found a series of genetic variations that cause a predisposition to different kinds of mental illness.

“But our goal was more far-reaching than simply to find genetic variants which increase the risk of developing mental illness -- we wanted to use genetics to understand its biology. To find out which biological processes give rise to the development of the illnesses," explains Thomas Werge, clinical professor of neuropsychiatry from the University of Copenhagen and head of research at the Institute of Biological Psychiatry at Capital Region Psychiatry, Sct. Hans Hospital.

Werge leads the Danish group in the international scientific collaboration, the Psychiatric Genomic Consortium, which has mapped the biological causes of mental illness, and coauthored the scientific paper.

Mental illness caused by shared biological disorders

In the new study, scientists looked to the genes and genetic variants that produce an increased risk of mental illness as their point of departure in order to determine what biological processes they affect.

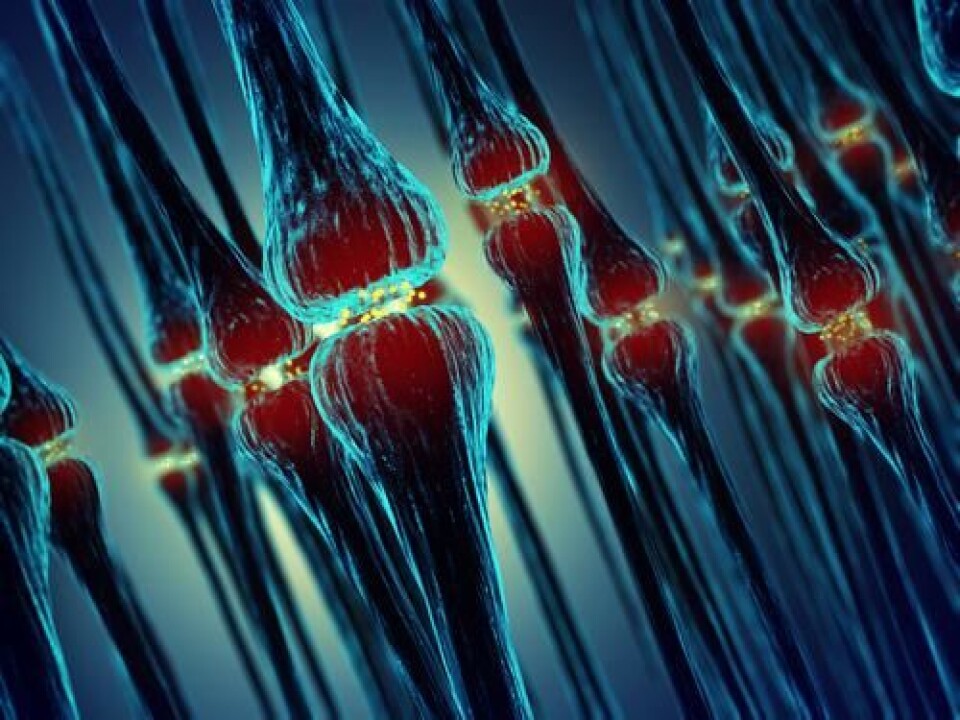

They discovered that three biological processes are disrupted to a greater or lesser degree in the case of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and clinical depression. They are the activation of the immune system, e.g. in connection with an infection; the protein which manages the activity of our DNA; and finally, the processes in the synapses of the nerve cells which manage communication between these cells.

What do the defective genes do?

Søren Brunak is a professor of system biology at the University of Copenhagen and biocomputing at DTU. His job is to map the body's biological systems.

According to Brunak, it will be increasingly necessary to start thinking in terms of how genes are involved in biological processes instead of simply studying the genetics.

“We have come to realise that we humans have far fewer genes than first thought. So many of the genes we do have are likely to be involved in more processes than we

thought. Therefore, it makes good sense to examine biological systems rather than studying individual genes.”

Poul Videbech, a professor of psychiatry at the Department of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, finds it slightly more difficult to be enthusiastic about the new study.

“I find it difficult to mobilise a lot of enthusiasm. What we discover is that we have thousands of significant genes. And because the signals are so weak, we need to have colossal volumes of data," he says. “We know that heredity is considerable in the case of e.g. schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but the environment is also significant. Especially in connection to severe depression.”

Genetic findings pave way for medication development

The new study has brought us closer to understanding the biological pathogenesis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. “The next step is to keep on testing people with these three mental illnesses in order to verify the hypothesis that these three biological processes have been disrupted,” says Werge.

According to him, if and when we get it right, it will be possible to develop medications that can normalise these processes and therefore better treat the illness itself rather than just the symptoms.

“The hope is that this incipient understanding of the causes of mental illness will enable us to development medications which modify the disrupted biological processes, so that the illnesses can either be remedied or not develop at all," he explains.

Professor Brunak agrees. “These studies will give us a better understanding of how the underlying molecular machinery works and which processes are disrupted. And then it will become much easier to develop treatments which we know will work, and why," he points out.

New treatment of mental illness still far off

Professor Videbech doubts a study like this one will lead to new treatments in our day.

“Although I believe we need to conduct studies of this kind, the danger is that what comes out of them may be very limited. There's not much indication that new treatments will de developed. They will certainly take a good many years to develop,” he says.

For Birkelund, it makes sense that she may always have been carrying the illness. “I think it’s something I was born with. I remember when I was seven years old and had an upstairs bedroom, there were also people keeping an eye on me through the window. In those days it was boys from school I didn't like,” she explains.

It would be a tremendous relief to her if scientists found that paranoid schizophrenia -- the men in black, the voices of boys peering in through her upstairs bedroom window – was ‘simply’ an imbalance in her biological processes.

“It actually makes good sense. I've read that schizophrenia can be due to some failure in your early years, but I simply don't understand how it could have been my

Mum and Dad's fault. Perhaps this can explain it,” she says.

-----------

Read the original story in Danish on Videnskab.dk

Translated by: Hugh Matthews