Lone wolves are overrated

So-called lone wolves, criminals who operate alone, are not as crafty and well-organised as we might think, according to a Swedish expert.

This week the Swede Peter Mangs was charged with the murder of three people and the attempted murder of a dozen others in Malmö.

Mangs and the Norwegian mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik and lots of other extreme and violent criminals are often called lone wolves by the media, law enforcers and researchers.

What does that actually mean?

According to psychologist Knut Sturidsson of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, the image of a single wolf on the prowl misses the mark: “I don’t think the concept really covers the essential character of these criminals,” he says.

“The term lone wolf gives associations of a fairly competent criminal, one with authority, prowess and knowledge. But in most cases these persons aren’t as talented or calculating as they seem.”

Lone wolf − or stray mutt?

Sturidsson has years of experience assisting the Swedish Police with psychiatric evaluations of criminals. He recently presented an analysis of Peter Mangs at a conference of the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals.

A lone wolf, as defined in criminological and psychological research literature, is a person who operates alone, who doesn’t belong to any organised terror network or group, but who is inspired by a broader political, religious or ideological agenda.

“The term plays well in the media, which loves strong imagery, but it’s unfortunate,” says the psychologist.

Mangs is described by most people as a recluse, as quiet and peculiar.

“These are usually persons who are simply oddballs who also commit atrocious crimes. With some ridicule intended, in my lecture I chose to call them ‘stray mutts’, dogs with no masters.”

Don’t jump to conclusions about insanity

When people do hideous things like planting bombs or committing mass murder, we tend to think they must be crazy. Legal insanity is a central issue in Anders Behring Breivik’s ongoing trial, as it will be when the Mangs trial starts next week. Mangs has already been diagnosed with autism.

But the span of human behaviour is immense and a person doesn’t have to be crazy to be extreme.

Take a guy like the Austrian Josef Fritzl, for instance, who shut his daughter up in a dungeon in his basement for years. Maybe he was just an odd and mean person. I think we need to have the right to say this was a nasty bastard.

“I don’t think we should be thinking so much in terms of psychoses," says Sturidsson. "We always look for an explanation of such acts and a couple of hundred years ago we might have blamed the Devil. Now we use a psychiatric idiom.”

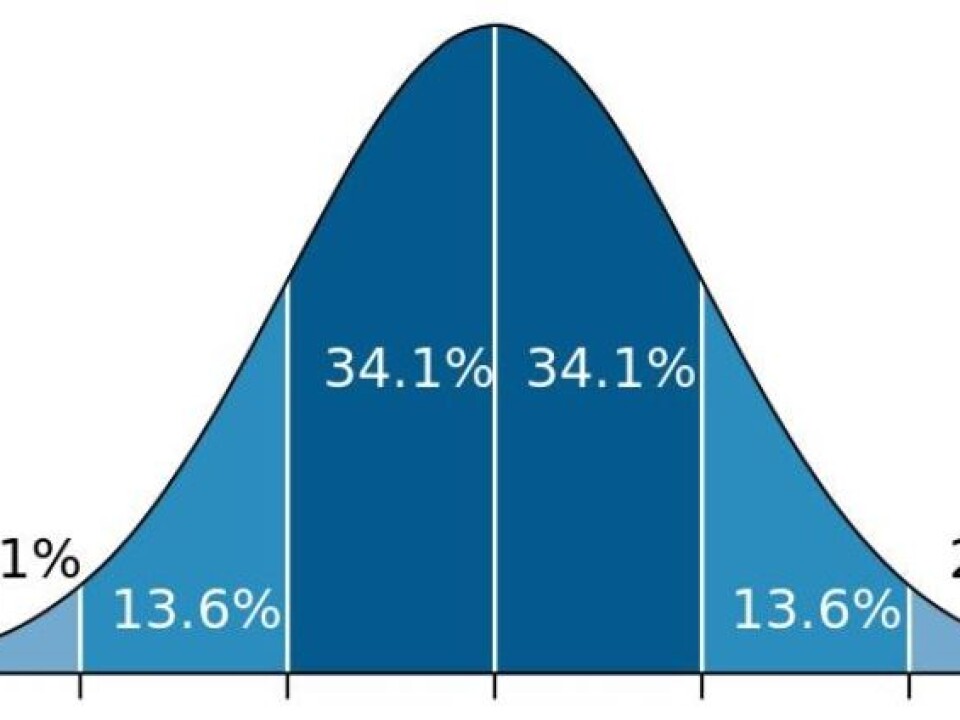

He points to the normal distribution (Gaussian) curve in which most everything, from shoe sizes to hair colour and behaviour can be plotted on a graph against a norm.

It’s a bell-shaped curve that can be divided into two medians as the outer points of the most normal part of the curve. About 70 percent of all behaviour can be placed between the two medians.

“We are seven billion people on this planet so there will be quite a few on the extreme fringes. So 0.1 percent of seven billion is a lot of people. Nevertheless, they won’t necessarily qualify for a psychiatric diagnosis,” he says.

“Take a guy like the Austrian Josef Fritzl, for instance, who shut his daughter up in a dungeon in his basement for years. Maybe he was just an odd and mean person. I think we need to have the right to say this was a nasty bastard.”

Not like your ordinary villains

Instead of searching for psychiatric causes, maybe a systemisation of common denominators for “odd criminals”, or lone wolves, might be a better approach.

Through research and experience the police have accumulated a fairly comprehensive list of characteristics regarding what they consider 'ordinary' criminals, in other words robbers, muggers and the like.

Sturidsson says that ordinary perpetrators of crimes are over-represented in substance abuse statistics, they exhibit psychopathic traits more often than the rest of the population and a juvenile crime record will often indicate a risk of continued criminal behaviour later in life.

But such lists are of little value when trying to spot lone wolf criminals.

“If we look at these odd perpetrators, as I call them – persons like Peter Mangs – we don’t see this sort of connection. Traditional tools don’t work for making a list of risk persons when it comes to such perpetrators,” he says.

Another motivation at another time

The psychologist explains that “oddball” perpetrators usually haven’t had much previous contact with the police. They tend to shy away from social situations and don’t get along well with other people. They are also far less likely to be substance abusers than other criminals.

These special criminals have a higher-than-average interest in weapons and violence, they have no personal relationship with their victims prior to the crime, but they have strong political, religious or ideological persuasions.

Opposition to multiculturalism and xenophobia are core elements in both the Breivik and the Mangs cases. Sturidsson stresses that he hasn’t studied the Breivik case specifically, but he points out that it’s not uncommon for people to seek out issues to hang their frustrations on.

“Of course one is influenced by the society one lives in and people like Peter Mangs are attuned to the Zeitgeist.”

“In another era or in another place this type of person would also become a killer, but they would have linked their actions to some other contemporary issue.”

Many weirdos, but only a few are killers

Law enforcement, security forces and others are striving to improve lists of risk factors. Reid Meloy, an American forensic psychiatrist, has studied many characteristics which indicate that someone could pose a threat.

Both Meloy and Sturidsson emphasise that the research field is still in its infancy. The personality traits they mention cannot and should not be used to hunt for the next perpetrator down the line.

“There are so many weird people who match these criteria but who will never commit any violent crimes. So the traits aren’t of any use to the police as a tool for finding people beforehand,” says Sturidsson.

“I know the reaction came from society in Norway and elsewhere after the terrorist attack last summer that this must never happen again. Of course I understand this goal, but I think it’s unrealistic. People have always carried out such acts.”

He points out that even in China, a country where surveillance is as pervasive and intrusive as it gets, gruesome and extreme crimes still occur now and then.

“Finding empirical support for the risk factors we see in such cases pivots on a long process. We now know that psychopathy often links to violent crime but it has taken us many years to reach that conclusion,” he says.

“We don’t know which constellation of antisocial behaviour, of strong convictions and these other traits make people turn violent. We can only make strides toward an understanding of it by conducting studies and amassing a mound of knowledge from the bottom up.”

--------

Knut Sturidsson presented his analysis “Lone wolf or stray mutt?” at a conference arranged by the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals in Krakow, Poland, on 26 April 2012.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling