Ancient marine lizard had telltale fish tail

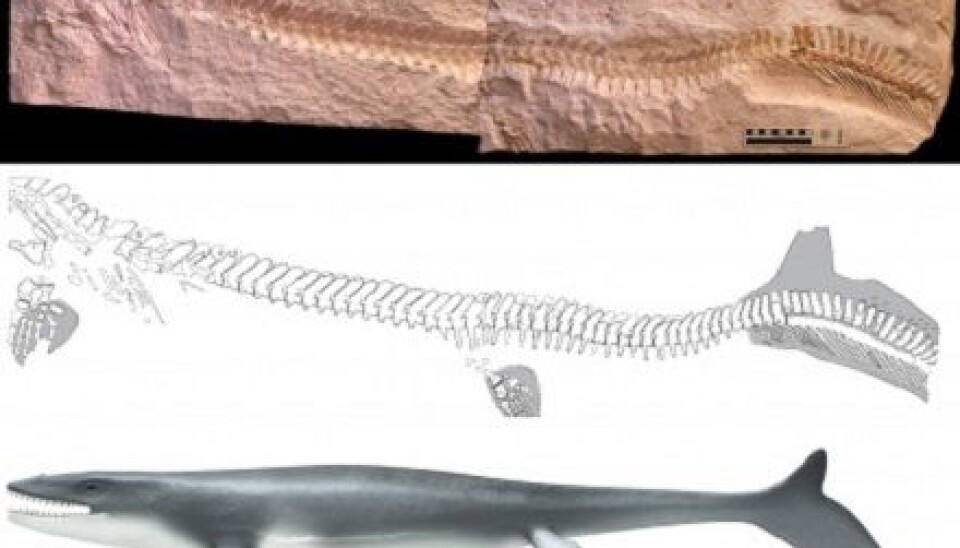

The discovery of a fossil tail fin of the extinct marine reptile prognathodon is revolutionizing perceptions of these giant predators, which dominated the oceans in the Cretaceous Period.

Marine reptiles have long been thought to be fish-like, but with long slender bodies and tapering fins. Palaeontologists believed they swam by undulating through the water, like an eel. But that view will probably have to be revised.

An international team of researchers, led by a Swedish scientist Johan Lindgren of Lund University, have discovered clear imprints of a fish-like tail fin on a prehistoric Prognathodon, a genus in the family of marine reptiles called mosasaurs.

The Prognathodon could be up to 15 metres long. Mosasaurs ruled the seas during the Cretaceous Period (from about 145 million to 66 million years ago) at the same time as dinosaurs did on land.

“After trying to reconstruct the appearance of the tail fin from skeletal evidence for several years, suddenly I found myself facing definitive proof,” Lindgren told the magazine Nature Communications.

Better swimmers than believed

The proof that the genus was fish-like, with characteristics such as a two-lobed tail fin, was evident in the imprint from the skin of the fin and fossilised soft tissue.

“It was such a fantastic feeling! I was euphoric and couldn’t sleep for the next two days,” Lund said.

“A fish tail meant the animal could reach much higher speeds. That also means it could catch prey and escape much faster. It would have a quicker lifestyle,” says Associate Professor and Palaeontologist Jørn Hurum, of the Museum of Natural History in Oslo.

“The presence of a tail fin also means that it didn’t just stay close to shore, as we used to think. It could swim far out into the ocean.”

Another group of marine reptiles, the ichthyosaurs [Greek for “fish lizards”] evolved around 240 million years ago and died out 80 million years ago.

They were perfectly adapted to life in the sea with their dolphin-like bodies and large fish tails. The mosasaurs flourished just as the ichthyosaurs became extinct.

Until now there were doubts that competition from mosasaurs was the cause of ichthyousaur extinction, but Hurum now wonders whether the connection was there after all.

“Now that we see that the mosasaurs were much better swimmers than we anticipated, this is very exciting. This might provide the answer to the puzzling extinction of the ichthyosaurs,” says Hurum.

Young example

Over the course of the Cretaceous, the mosasaurs became the dominant predators in the sea. They could reach a length of up to 15 metres but the specimen with the tail fin was a youngster, just about 1.5 metres.

The fossil was found in Jordan in 2008, and was incorporated into the collection of the Eternal River Museum of Natural History, in Amman, Jordan.

Lindgren was not among those who excavated the fossil. He arrived in Jordan in December 2011.

Nearly the entire body of the specimen is intact, not just the head and tail.

The reptile’s fish-like body shape and bi-lobed tail fin resemble the physiology of other, adult, sea creatures – not just the extinct ichthyosaurs, but also sharks and whales. It looks like an upside-down shark tail.

“The fossil also shows how new discoveries can change general conceptions about the lives and habits of extinct animals. It also illustrates what fantastic adaptabilities reptiles possess,” says Lindgren.

He contends that the evolutionary history of the mosasaurs is one of the best examples of evolution on a grand scale, and how the physiology of an animal changes to adapt to new environments.

--------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling