Living fossil lives only on two rocks

A small herb from the past has miraculously survived on two adjacent vertical cliffs with the help of ants.

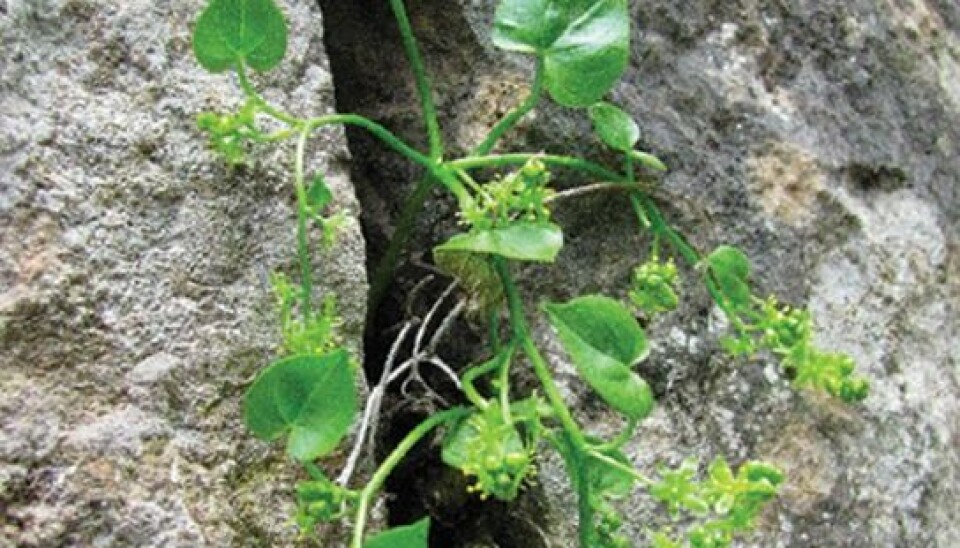

One of the world’s rarest plants is literally clinging to life on two adjacent cliff sides on the Spanish side of the Pyrenees.

All the world’s 4-5,000 individuals of the small herb Borderea chouardii can be found within an area the size of a football field.

This yam-like herb, with its heart-shaped leaves and unassuming green flower, has been growing into crevices in the rock some 850 metres above the sea for millions of years.

Now Jens Mogens Olesen, a professor in ecology at Aarhus University, and two Spanish scientists reveal that the herb has a unique survival strategy in which it allies itself with three ant species. Only through these partnerships can the herb survive.

Herb discovered in 1952

The herb is a relic of a time when Spain was tropical and covered in rainforest.

As the planet subsequently cooled down and the tropical zone was pulled towards the equator, the little tropical herb remained perched on its Spanish rock.

Its closest relatives are extinct, but the Borderea chouardii strangely managed to pull through. And from their high-rise home they have lived to see Ice Ages and civilisations come and go.

This living fossil resides in an area so inaccessible that it wasn’t discovered until in 1952.

Olesen’s Spanish colleague, Maria B. García of the Instituto de Ecologia Pirenaico in Zaragoza, began studying the herb 17 years ago and has returned to the area every year since then to count and monitor the herbs, which have now been protected.

Olesen, who became involved in the project three years ago, says it has not been easy to study the herb:

“We used ropes to lower us down, and we spent many, many hours crawling around while hanging on the rope,” he says about the study, which has just been published in the scientific journal PLoS ONE.

Herb’s sex life revealed

The scientists have solved two riddles:

It’s very rare to see plants using the same animal for pollination and for dispersion.

- How the herb manages to reproduce, despite the individuals being separated on a vertical rock surface.

- How it defies gravity and avoids plunging down to the foot of the cliff.

Let’s start with the one about sex: the individuals are either male or female. In order for reproduction to take place, pollen needs to be transported from the male to the female flower.

This is usually taken care of by the wind, but none of the sticky microscope slides that the researchers set up beside the male herbs picked up any pollen. So in this case, it couldn’t have been the wind.

Another explanation could be flying insects. To test this hypothesis, the scientists decided to scrutinise the herbs with their own eyes. For a total of 76 hours they hung in ropes trying to spot something. They noted that bumblebees and butterflies visited other plants on the cliff, but they steered clear of the little herb.

This is probably a world record for herbs.

In fact, very little happened at all.

Ants sort out the pollination

But occasionally a few ants – of the Lasius grandis and Lasius cinereus species – passed by, and it soon became clear that it’s these ants that pollinate the flowers.

The herb has arranged its flowers so that they point toward the rock and this enables the ants to reach the nectar.

As the ants slurp the nectar, they’re lubricated in pollen which, with a little luck, ends up on the female part of a flower further up the cliff.

The ants ‘carry’ the plant

So that’s the sex mystery solved then. But how about gravity? How did the herb make its way hundreds of metres up a cliff in the first place?

The answer, again, is ants. But this time we’re talking about a third species – Pheidole pallidula – which pays regular visits to the herb when it seeds.

The herb has another clever trick up its sleeve: it equips each seed with a small fatty compound which the ants find highly palatable. The ants then drag the seed off to their nest in the rock’s crevices, where the seeds that are not eaten are left to germinate.

The three scientists revealed this intimate partnership by gluing small plastic containers with herb seeds on the cliff.

Only the P. pallidula ants showed any interest in these containers – and they even preferred the herb’s seeds to other related foods.

A risky reproductive strategy

”It’s very rare to see plants using the same animal for pollination and for dispersion,” says Olesen.

Leaving the entire reproduction to one single type of animal is a rather risky strategy.

But as a buffer against extinction – for instance if the ants decide to find themselves a more suitable place to live – the herb has yet another trick up its sleeve:

It can live for up to 300 years. Maria García has demonstrated this by counting leaf scars on the tuber, which produces a new leaf every year.

“This is probably a world record for herbs,” says Olesen.

The herb-ant relationship is only just effective enough

In the 17 years that Maria García has been counting, only eight new plants have sprouted per year, on average. And since some individuals also die, the population only just grows enough to survive.

”It constantly lives on a razor’s edge. It has a really bad propagation, which is entirely dependent on ants,” he says.

On the other hand, it lives a tranquil and stable life up there on the cliff, free from the dangers of grazing animals such as sheep and goats.

It only grows on the north side, where the sun doesn’t shine. Here conditions are always slightly humid and the temperatures are fairly constant. In winter, the rock keeps warm, and in summer it maintains a nice and cool temperature.

“It’s well protected,” says Olesen. “However, a few years ago, some rocks fell down due to natural causes, and this had a negative effect on the Borderea chouardii population.”

Ultimately, the survival of this strange herb could depend on the strength of the rocks it's clinging to. There have also been attempts at ensuring the herb’s survival by trying to grow it elsewhere. Only time will tell if that will work.

----------------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther