Huge meltwater reservoir found under Greenland ice

A reservoir of meltwater the size of Ireland has been found within Greenland’s ice sheet. The reservoir may increase the melting of the inland ice in the future and provides fundamental new insights into the dynamics of the Greenland ice cap.

An international team of scientists has found a hitherto unknown reservoir of meltwater in Greenland's southern ice sheet.

The aquifer (see Factbox) is stored in the air space between particles of ice and covers an area of 70,000 square kilometres.

The depth of the aquifer is between five and 50 metres and the water in it lies about ten metres beneath the ice sheet surface.

The discovery provides important new clues about the melting of the inland ice:

“Finding liquid water where we did came as a big surprise,” says Professor Jason Box, of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS), who was one of the scientists behind the discovery.

”This opens up an entirely new chapter in glaciology. Up to now, we have regarded the inland ice as consisting of ice and snow, but now it turns out that liquid water is also a permanent part of the inland ice. We now need take this into account in our calculations of meltwater runoff and sea levels.”

Not a consequence of climate change

An idea which immediately suggests itself is that the meltwater reservoir is caused by climate change, but according to the professor this is not the case.

He does not believe that climate change will have any significant effect on the size of the aquifer in the future, nor does he think that the new discovery will affect the forecasts about melting from the inland ice.

If the water level in the aquifer were to rise, it could make the inland ice even more sensitive to climate change. If the surface of the water reaches the surface of the inland ice and starts to form small lakes, it would make the inland ice darker, and that would lead to an increased absorption of heat from the sun, which in turn would lead to a dramatic increase in the amount of melting.

Since the initial discovery of the aquifer in 2011, its size has not increased much, despite 2012 being the year with the greatest melting of the ice cap in recent times.

This, according to Professor Box, is another indication that the aquifer is not a result of climate change, although he believes that further studies are needed before any clear-cut conclusions can be drawn from this:

“If the water level in the aquifer were to rise, it could make the inland ice even more sensitive to climate change. If the surface of the water reaches the surface of the inland ice and starts to form small lakes, it would make the inland ice darker, and that would lead to an increased absorption of heat from the sun, which in turn would lead to a dramatic increase in the amount of melting,” he says.

“But in order to reach any conclusions about the full implications of our discovery, we need to examine it in more detail and over a longer period.”

How the aquifer arose

Box believes that the aquifer is a result of the melting of ice and snow in summer when temperatures in southern Greenland are above freezing point.

The meltwater percolates down through the dense snow in summer. Winters in southern Greenland see great amounts of snowfall, and this thick snow cover insulates the aquifer from the cold winter air temperatures, thus allowing it to remain liquid throughout the year.

“This is a hitherto unknown dynamic of the ice sheet,” says the professor.

As the ice and snow is melting, filling up the aquifer, there must also be a runoff of water at the same rate as it is being filled – otherwise the water level would increase faster than the scientists have observed.

”We have yet to figure out where in the aquifer the water runs off, but it probably runs off through small channels in the ice that lead the water down into lower-lying areas where it can flow over the ice and out to sea,” explains Box, adding that this is something that they will be studying in more detail in the future.

Accidental discovery

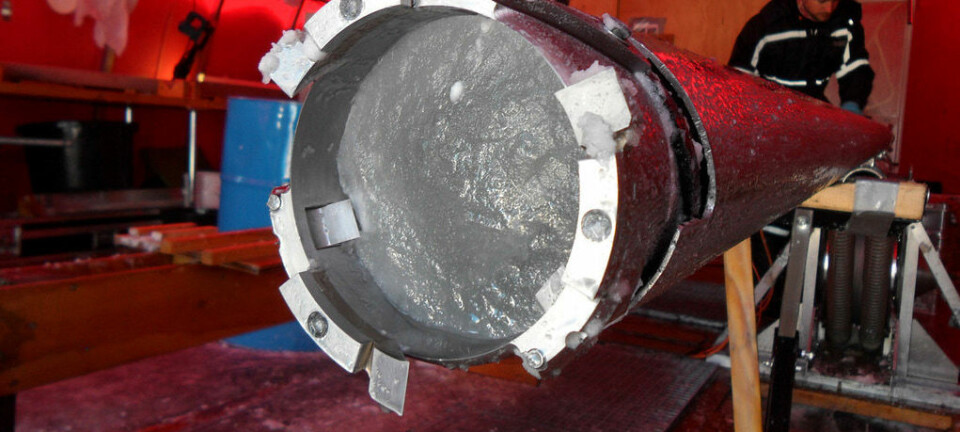

While drilling for ice core samples in 2011, they found liquid water pouring off the drill. This came as a quite a surprise, as air temperatures in the area were well below the freezing point.

They tried to move their drilling equipment a few kilometres away and again they found liquid water.

Having studied radar images of the area, they discovered a clear outline in the water’s reflection below the snow.

“This is a very large area and it is probably unique to southern Greenland, as the formation of such an aquifer requires large amounts of snowfall, and only southern Greenland has this amount of snowfall,” says Box.

“We will now study how this area affects the dynamics of the ice sheet and whether climate change has had any relevant effect on the aquifer.”

---------------

Read the Danish version of this article