Caves will reveal Greenland climate from before the ice sheet

GREENLAND: A team of scientists has explored some of the most remote caves on Earth to uncover Greenland’s climate before the ice sheet formed. Preliminary results are exciting, say scientists.

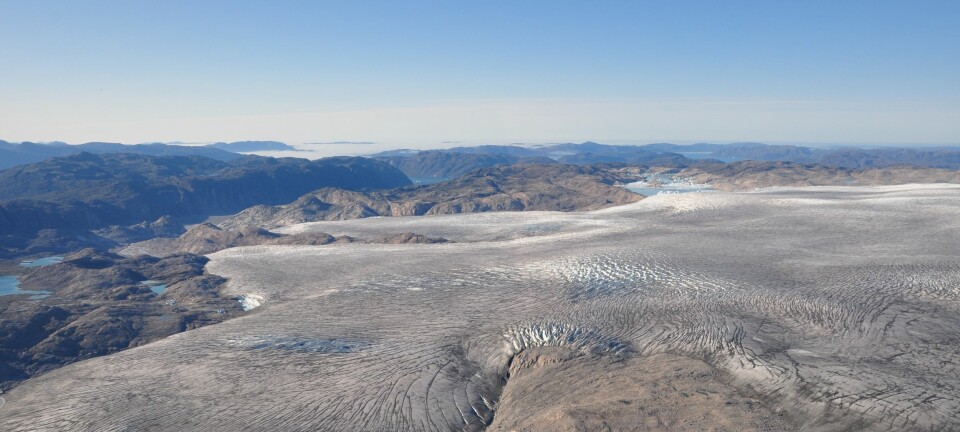

High in the Arctic Circle at 80 degrees north, scientists have been exploring some of the world’s remotest caves to see what they can tell us about Greenland’s climate before the Greenland ice sheet formed.

A team of scientists trekked through the remote landscape of northeast Greenland for three days before reaching the caves. Inside, they found rock formations, some of which are up to 500,000 years old.

“This will be the first record of palaeoclimate derived from caves so far north and we now have the prospect of extending the [climate] record for Greenland beyond the limit of the ice cores,” says lead scientist Gina Moseley, from University of Innsbruck, Austria.

Moseley presented her team’s preliminary findings at the 2016 European Geosciences Union General Assembly.

Rock formations reveal climate up to 500,000 years ago

Moseley and her team collected 16 samples of speleothem--rock deposits that form when rainwater or melted snow percolates down through limestone and enters a cave as drip water.

It is generally too dry for speleothems to form today in northeast Greenland, so Moseley knew that the samples they found were old and must have predated the Greenland ice sheet. Preliminary dates suggest that the samples formed at various times between 220,000 and 500,000 years ago.

Just the presence of speleothems in the caves tells us that northeast Greenland was once wetter than it is today, as they need flowing water to grow, says Moseley.

This suggests that atmospheric circulation must have been very different than it is today.

“There is a big question as to how you get moisture to this part of Greenland as it’s so dry today,” says Moseley. “Climate models for this century show a retreat of Arctic sea ice and storms tracking north. So our hypothesis of a warmer, wetter world back then fit with projected climate scenarios for the future,” she says.

Video: Northeast Greenland Caves Project.

Preliminary data need to be confirmed

Moseley and her team have also analysed the chemistry of the speleothem samples and she believes that they record a clear climate signal from which they can figure out how different the climate was when these cave deposits formed.

But she emphasises that all of these data are still preliminary, and that it is too early to draw any specific conclusions just yet.

“We’ve done some stable isotope analyses and we see some very large shifts, so there is a climate signal in there. But we don’t know exactly what it is yet,” says Moseley.

The scientists now plan to carry out more analyses to piece together Greenland’s pre-ice sheet climate.

Colleague: Exciting Project

The project has been met with excitement from a colleague who also studies historical climate change.

“The project is a truly amazing and inspiring journey of scientific discovery and adventure, in its own right, with the aim of developing the first cave-based records of palaeoclimate from the arctic,” says geochemist Adam Hartland, from The University of Waikato, New Zealand. He was not involved in the new research but is familiar with the preliminary results.

Hartland expects the project to lead to important records of climate for Greenland, which he describes as a “critically important region for the global climate system.”

Read more: Greenland melt linked to weird weather in Europe and USA

Three-day trek to unexplored caves

To reach the caves Moseley and her team flew to a remote corner of northeast Greenland. They crossed a lake in an inflatable dinghy before embarking on a 3-day trek across valleys, plains, and loose scree hill slopes to reach the caves.

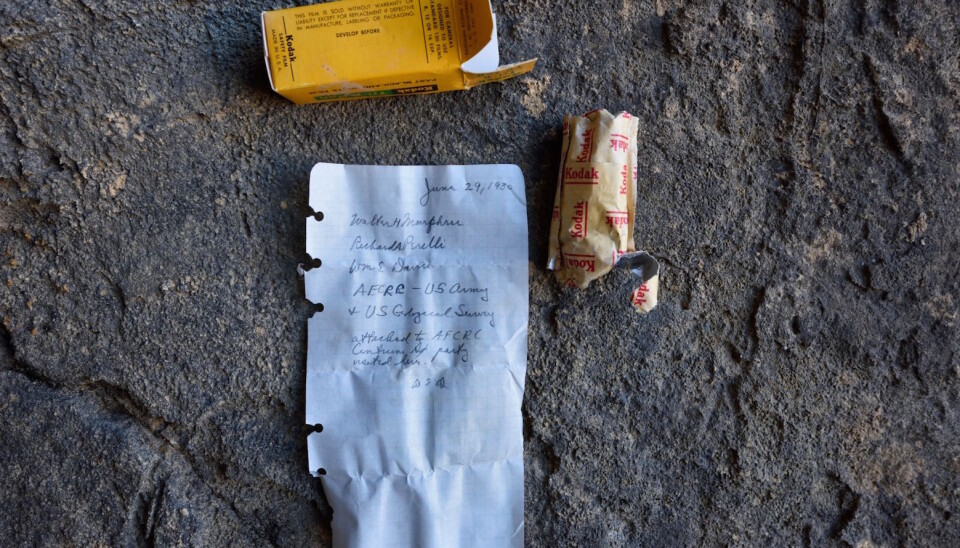

The last known visitors had been a team of cavers in 1983. Before that, a team of scientists from the US geological survey explored some of the caves while looking for aircraft landing sites during the cold war.

The expedition team also discovered some new, undocumented caves.

“There’s one particular high-level cave that we know no one had been in before and it was covered in ice crystals. That was really amazing. And knowing that the arctic is warming, and that we might be the only people to ever see that was really special,” says Moseley.

But exploring such a remote landscape is hazardous, despite the thrill of being the first humans to ever step foot in some of these caves.

“I was on eggshells the whole time I was there. As exciting as it is, I knew that we all needed to get home safe and well and in good health,” says Moseley. “We even talked about having our appendices removed before the trip,” she says.

“It hit me at the end, when we were due to be picked up [by aeroplane]. The weather was great where we were, but south of us [where the plane was taking off] there was terrible weather and we were stranded for a couple of days as no one could get to us. We realised that if there’d been an accident, no one could get to us,” says Moseley.