Power to the people - How to make the low-carbon energy transition work

A recent study of two successful energy transitions in Denmark and Germany shows that transparency and community participation are essential to drive the clean energy agenda forward at the local level.

Most people agree that something is not quite right in the way we exploit our planet. Resource depletion, environmental destruction and pollution have indeed reached alarmingly high levels.

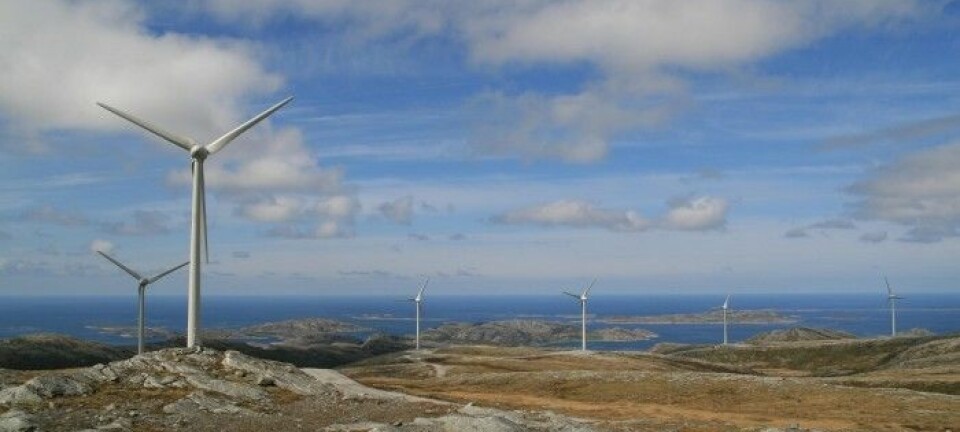

Removing fossil fuels from the picture and replacing them with renewable energy is not problem-free. But on the Danish island of Samsø and the village of Feldheim in Germany, citizens have done just that for their entire electricity and heating system.

In our recent study we set out to discover how they did it.

Read More: Can we really limit global warming to “well below” two degrees centigrade?

The challenges of low-carbon energy transitions

Climate change is a particularly serious global challenge, and one that can significantly magnify many other challenges, such as poverty and inequality.

The core cause of climate change relates to our unsustainable patterns of energy production and consumption and the related emission of greenhouse gases.

So, governments all over the world have launched projects and policies to support the implementation of renewable energy technologies, like wind, solar or biomass as part of the transition towards low-carbon energy systems.

These are widely seen as necessary and economically available alternatives to the status quo.

But the implementation of such projects is often met with fierce opposition at the local level. Ranging from protest letters against planned wind parks in Norway, to demonstrations against geothermal power plants in Germany, and all the way up to bomb attacks against large hydropower dams in Nepal.

Read More: The transition to green energy has not really begun

Unfairness, not ignorance, drives opposition

Contrary to the long-held belief that these people are either not educated enough, selfish, or too short-sighted to see the greater benefit of renewable energy, those affected often seem to be concerned with the same underlying issue: Fairness.

There’s a growing body of scientific literature on energy justice that indicates that local communities often oppose energy projects due to a perceived lack of fairness in both the decision-making processes and in the distribution of project outcomes.

Citizens often feel that they are informed too late or too little, and are not consulted about their opinions of such projects. When opinions are heard, citizens feel frustrated if their input is not taken into consideration and they are left feeling that they had no chance to contribute and participate meaningfully in the process.

Renewable energy projects do have benefits, such as access to local energy sources, financial revenues, or jobs for local plumbers, engineers, or farmers. But there are also costs, such as an obstructed view from the kitchen window, financial investments, and noise or shade.

If the local community perceives the distribution of costs and benefits to be unfair, this can easily trigger protests. For example, when a wind farm is owned by a company that reaps all the financial benefits, while the local village is stuck with an obstructed view and disturbances to their wildlife.

Read More: New study estimates the carbon footprints of 13,000 cities

Overcoming opposition in Denmark and Germany

Of course, it is easy to highlight past mistakes of project planners or policymakers. But the real question for our research team was: How can we make it work?

We decided to look into two community projects that are seen as widely successful:

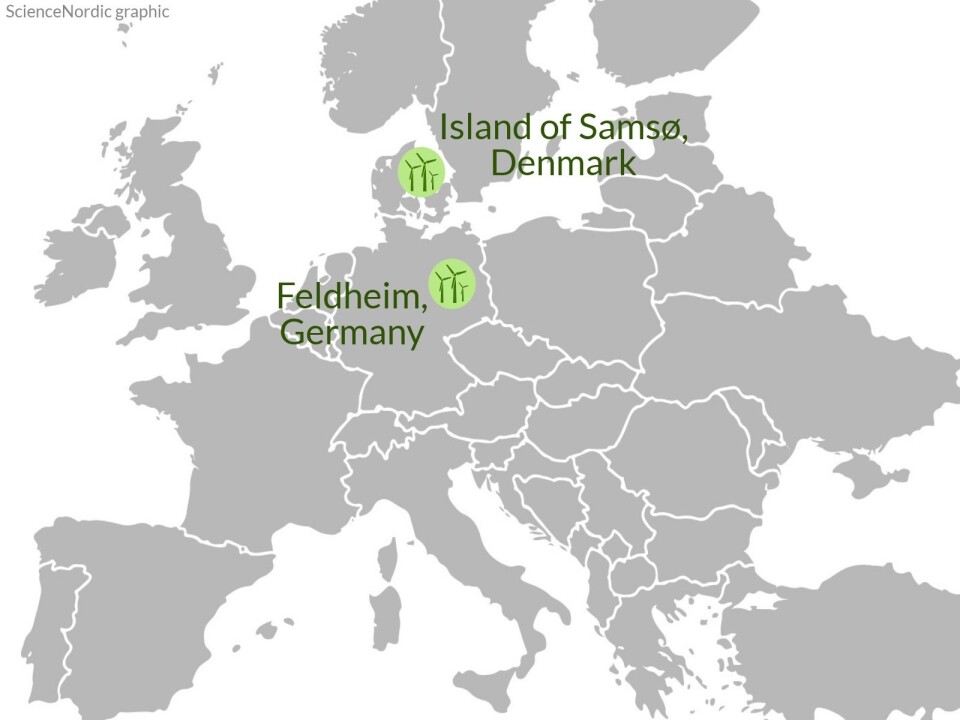

- The Danish island of Samsø. A small community of less than 4,000 citizens who managed to switch from fossil fuels to 100 per cent renewable electricity and heat within ten years.

- The German village of Feldheim, which is the first energy self-sufficient settlement in the country.

We were curious about these seemingly successful low-carbon energy transition cases: How did they address issues of fairness while developing the project or the distribution of the outcomes, and what can we learn from them for future projects?

Read More: How to make greener biofuels

Involve locals from the start

It turned out that both communities went through long negotiations during countless community meetings. The project managers encouraged participation early on through local newspapers and blackboards and received feedback during those meetings or through protest letters.

Before becoming success stories, both communities faced fierce conflicts on issues such as the optimal location of the energy infrastructure, land titles, and investment options when the transitions started to take place. But both communities set up institutions to manage and monitor the local energy transition and found ways to distribute the benefits of the projects.

Samsø came up with community ownership and a shareholder system that allowed everyone to buy shares in windmills, while Feldheim also decided to invest financial returns in community projects such as a new football pitch.

Read More: Future cities could be lit by algae

What can we learn from these cases?

The take home message is that the way projects are planned matters to local people.

Communities are concerned about the impact of energy projects on their local society and it is crucial that their opinions are heard and that the outcomes of the project are distributed in a visibly fair manner among the community.

The cases of Samsø and Feldheim show that these aspects contribute tremendously to the perceived legitimacy of a project. A transparent and inclusive process where citizens can openly discuss the pros and cons of new energy systems can foster success and long-term acceptance.

But this type of approach takes time. And given the urgency to tackle climate change, future low-carbon energy transitions need to start now.

Read More: Scientists: Three years left to reverse greenhouse gas emission trends

---------------

Read this article in Danish at ForskerZonen, part of Videnskab.dk